In the previous article, we started with the basic question of why logging your Chinese learning is a good idea. We saw that it has a number of benefits for your learning, including making it visible, creating an accurate record of it, making it possible to set better goals, and enabling you to share your progress with others for accountability and assistance.

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcast, Overcast, Spotify and many other platforms!

You might want to read the previous article before continuing: Chinese language logging, part 1: Why and how to track your progress

Chinese language logging, part 1: Why and how to track your progress

Beyond the above benefits, we also briefly discussed that logging can help you analyse your learning and create a better balance between different areas and skills. In this article, we’re going to look at how to break down your learning into categories, how to analyse your learning and how to make sure that you balance different skills correctly.

Let’s start by looking at different ways of breaking down language learning!

The four basic skills: Listening, speaking, reading and writing

The most commonly used categorisation of language skill is the four basic skills: listening, speaking, reading and writing. These are widely used both by professionals and laypeople to describe language ability. Many language proficiency tests have one part for each skill (such as HSK and TOCFL for Chinese, and IELTS and TOEFL for English) and many teacher organisations and educational frameworks also split language ability in this way.

It can be argued that a fifth category is needed for vocabulary, especially in Chinese, considering that characters (especially handwriting) isn’t covered by the four basic skills. For example, one can be good at typing emails and essays in Chinese on a computer, but still be unable to even write basic notes by hand. The nature of Chinese characters also means that this area requires significantly more effort than in most other languages. Indeed, it’s not an exaggeration to say that this is the main reason why Chinese takes longer to learn.

I also rely on the four skills to sort articles on Hacking Chinese. If you look at the sidebar (bottom on mobile), you can see that I first sort by proficiency level (Beginner, Intermediate and Advanced) and then use the four skills, plus vocabulary:

In addition, I also use several categories related to learning Chinese, but that aren’t actually learning in itself, such as Attitude and mentality, Organising and planning and Recommended resources.

Hacking Chinese Challenges, where students set their own goals and try to accomplish as much as they can in a given area each month, also relies on the four skills for the most part. For example, there are three listening challenges and three reading challenges each year, along with some more specific challenges, such as singling out pronunciation as a focus area for a challenge.

The same is true for the roughly 500 resources I’ve collected on Hacking Chinese Resources: just click on one of the skills and it will only show you links tagged with that specific skill. Again, extra tags have been used to cover things like vocabulary or grammar that run across categories. You can also sort by difficulty level (beginner, intermediate, advanced) or by type of resource (such as information and advice, resource collections and tools and apps). Finally, the best feature of all is that you can combine any of these and find tools and apps for vocabulary learning suitable for beginners (currently 66 links listed).

Using the four skills to log your Chinese learning

Relying on listening, speaking, reading, writing and vocabulary to categorise your learning makes sense because it’s very intuitive and easy to do; everybody knows what the categories mean and you can just categorise or tag each activity accordingly. In the previous article, we looked at some things you might want to record, but I’ll stick to a minimum here. This is what I’ve been doing related to learning Chinese recently:

- May 17: Reading, 30 min, 国际中文教育中文水平等级标准 for article research

- May 17: Listening, 80 min, 李永乐老师 reviewing during a long run

- May 17: Vocabulary, 15 min, handwriting in Skritter

- May 18: Speaking, 60 min, 中文教学:理论与实践, a course I teach

- May 18: Vocabulary, 10 min, handwriting in Skritter

- May 18: Listening, 60 min, 中文教学:理论与实践 teacher presentations

- May 18: Listening, 15 min, 李永乐老师 new video

- May 19: Reading, 40 min, 霍比特人 reading aloud

- May 19: Vocabulary, 15 min, handwriting in Skritter

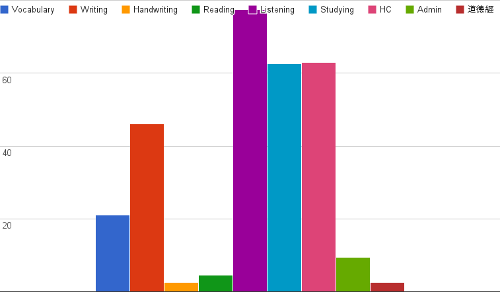

…and so on. If you log activity like this using a digital tool, which is something we will look at in the next article, you’ll be able to tally up time spent and generate neat charts, maybe once a month. Here’s a real example from my studying in May 2012:

As you can see, it doesn’t follow the 4+1 categories we discussed above perfectly. I have split handwriting from vocabulary, probably because I knew I would need to take in-class exams written by hand. I also haven’t logged speaking separately, but rather lumped a lot of hard-to-count activities into “studying”. I also have other categories you are probably less interested in, such as time spent writing articles here on Hacking Chinese (yes, the site is more than a decade old by now).

Please note that this is just an example. I had studied Chinese for around five years at the time and had identified what I thought would be my weakest links enrolling in a master’s program for teaching Chinese as a second language, taught in Chinese mostly for native speakers.

This is not what a healthy diet for most students would look like!

It’s just an example. It’s quick and easy to do. You can clearly see which areas you spend most time in, and which you are neglecting. Log your learning for one month like this, then compare with your goals for learning Chinese.

Are you really doing the right thing? Could it be that listening is actually what you should do, but you tend to spend most of your time checking online forums about language learning or listening to the Hacking Chinese podcast?

Beyond the four skills

If you do the above (or just look at my example), you will soon find that there are some problems with using only listening, speaking, reading and writing to track your progress. Adding vocabulary only solves part of the problem.

Here are some of the questions you might encounter:

- How do you count a discussion where you both speak and listen at the same time?

- Does learning about important aspects of pronunciation, such as tones or aspiration, not count at all?

- If grammar confuses you, does looking something up online count as zero studying?

- Does listening to something in the background count the same as doing your utmost during a mock listening comprehension test?

- Is reviewing in general equivalent to learning new things?

As we saw in the previous article, how we measure matters. If you use a system that tracks some things, but not others, you risk ending up neglecting the things you don’t track. The question about active listening and background listening above is a good example of this. If you treat both as the same, you’ll be able to log many more hours by only using background listening because it’s easier to do. This may or may not be the best approach, depending on your goal and your situation.

There are other frameworks that could be used, though. For example, in the CEFR (Common European Framework of Reference for Languages), there are separate categories for oral and written perception, interaction and presentation, as well as some auxiliary categories. If you use these to log your progress, conversations would go into the “oral interaction” category, which is different from introducing yourself. If you’re curious about this, I wrote more about CEFR in the article How good is your Chinese?

Logging the process of learning, not benchmarking the results of it

Let’s not lose track of our goal here: to analyse our learning so that we can make sure that we have a balanced approach. While we can certainly use the four basic skills plus vocabulary to do some analysis, things just aren’t that simple. Using spoken/written reception/interaction/production only helps a bit, but also makes things more complicated.

The most obvious problem is that the skills look at the result, not process. Most Western frameworks are built on can-do statements that talk about what learners can do on different levels in various areas, but that’s not what we are interested in here. Like I said in the previous article, logging is more about the process; if we want to look at the result, benchmarking is more suitable. That’s also what I talked about in the above-mentioned article about how to figure out how good your Chinese is.

To illustrate this point, even if you had a complete breakdown of your language practice for the past year using the four basic skills, that wouldn’t tell you much about what you might be doing wrong if you’re not seeing the results you expect.

While writing more will probably improve your writing a bit, it won’t be very effective if you don’t have a solid foundation in reading. Similarly, speaking can help you speed up the process of constructing sentences using what you already know, but it won’t really teach you anything you didn’t already know. For that, listening is required.

If you look at my own logging example above, you can see that I spent roughly ten times more time on writing than reading. I would normally advise you to do the opposite: read ten times more than you write! I had very specific goals at that time and had been reading a lot already.

In other words, if you’re struggling with a specific skill, the solution might not at all be to simply spend more time practising that skill! This can lead to much frustration and energy wasted doing the wrong thing. Most of the time, the reason your writing isn’t good is because you haven’t read enough. After all, the top three tips to people who want to write better Chinese is to read more: 20 tips and tricks to improve your Chinese writing ability

Paul Nation’s Four Strands

There are other ways to analyse your learning, though. One of my favourites comes from Paul Nation, otherwise probably best known for his work in the area of vocabulary acquisition. He calls his framework the Four Strands, and in difference to the other frameworks mentioned here, is meant to be used to analyse learning and teaching with the explicit goal of making sure that the right activities are included. In other words, the four strands are about what you do, not what skills that’s supposed to result in.

Let’s have a look at the Four Strands (mainly relying on Nation, 2007):

- Meaning-focused input refers to listening and reading activities where the focus is on deriving meaning, enjoyment or both. In order for this to occur, the language needs to be mostly familiar (at least 95%), otherwise the focus shifts to the language itself. In other words, this is extensive reading and listening. Studying a text where you have to look up every tenth word does not count. Listening to something you have to go through five times before getting the gist does not count either! This high level of familiarity with the content leads some people to think that this is not really “studying”, but the research that supports this type of learning, especially for reading, is substantial (see for example Nakanishi, 2015, and Pigada & Schmidt, 2006).

- Meaning-focused output is about using the spoken and written language to communicate with other people. Just like meaning-focused input, this means using largely language that you already know, without obsessing about grammar or pronunciation. While output won’t in itself teach you new things, it’s still important because it allows you to evaluate your situation. For example, when you talk with someone, you’ll quickly identify which areas you need to work on, and feedback from others will let you know if your pronunciation is on point or not. Output also allows you to build your mental models and figure out what you can not say in a language.

- Language-focused learning is when you focus deliberately on language features such as grammar or pronunciation (i.e. the bits that you were not supposed to focus on in the first two strands). Traditionally, this used to make up a very big part of what learning a language meant, but many more modern, input-heavy approaches downplay or even deny the benefits of explicitly focusing on language features in this way. Still, explicit focus on language features can be helpful to direct your attention, study systematic features in the language and sometimes also to contrast these with other languages you know. Another example of language-focused learning would be studying vocabulary itself, so much of the Chinese-specific challenges related to characters and handwriting belong in this strand.

- Fluency development means getting better and faster at what you already know. If an activity contains new words or grammar, it’s not fluency development. Fluency development involves both input and output, and both the spoken and written language. For example, the speed at which we can parse speech is highly dependent on familiarity with the words we hear. Processing a spoken sound the first time simply requires more resources than hearing it the fiftieth time! The same is true for reading. When it comes to output, while lots of input is the foundation of output, only listening will not make you a proficient speaker. Fluency takes practice to build up. A good example of this is that most students who have lived in a Chinese-speaking environment appear very fluent when talking about why they are learning Chinese. Why? Because they’ve practised talking about that specific topic many times since so many native speakers are curious and ask about it!

Using the four strands to analyse your learning

The four strands are well suited to analyse your language learning, which is not surprising because that’s why Nation created the framework. In his opinion, the four strands are supposed to be roughly balanced, meaning that each should take up ¼ of your time (or rather ¼ of the curriculum as Nation wrote this not for independent learners, but for teachers and curriculum designers). I don’t know if I agree with that, and as Nation himself says, the distribution is somewhat arbitrary.

One reason I don’t think that ¼ per strand is right is that I’m talking about your learning, not learning in a classroom with a set curriculum. This means that some practical aspects need to be considered. Learning is not limited to the classroom.

For example, in real life, for adults who learn Chinese for their own reasons, it matters greatly how various tasks fit into your life:

- Input in general is more important and also easier to fit into a busy schedule, especially listening. It’s hard to find opportunities for meaning-focused output for hours every day, but you sure can listen for hours upon hours each day. Listening also requires much less energy than speaking, so you can fit more of it into your schedule. Thus, the ideal amount of meaning-focused input is probably much higher than ¼.

- Language-focused learning should be used sparingly and only when necessary. Like I said above, some people (including teachers sometimes) incorrectly feel that this is what language learning is really about, so cutting down on it is hard. Do as little of this as you can, but don’t shy away from it when there’s a real need. Most people probably spend time on vocabulary separately (mainly because of Chinese characters), but beyond that, focus on your weaknesses. This should probably take up less than ¼ of your time, though.

I’ve written about these considerations and how optimise your learning more here:

Time quality: Studying the right thing at the right time

The time barrel: How to find more time to study Chinese

Conclusion: How to log and categorise your learning activities

Logging your learning according to the four strands is not as straightforward as using the four skills. An obvious problem is that the spoken and written language are treated in the same strand, so ideally, you need to combine the four skills with the four strands. Thus, you’d get “meaning-focused reading”, “meaning-focused listening” and so on. You could further split the “language-focused learning” into many categories, such as learning strategies, Chinese characters, pronunciation theory and so on. Then you could split “fluency development” into four skills. This way, you’d end up with a dozen categories.

For some people, this might actually be a good idea, but like I said in the previous article, the more complex your logging is, the less likely you are to do it. Minutes and hours you spend doing the recording itself don’t really count, although it could be argued that progress tracking or reading about progress tracking (now we’re getting very meta) is at least indirectly a form of language learning strategy (you learn how to do something so that that in turn later boosts your learning).

My suggestion is to do the following:

- Use the four skills (plus vocabulary) to log your time. This will give you an incentive to show up, and offers most of the benefits we talked about last time. It’s not perfect, but it’s good enough. It’s quick and easy to do. You don’t need to learn a new framework to use it either. When it comes to balancing, you should do much more input than output.

- Use the four strands when you plan your learning, build your routine and evaluate your learning. You don’t need to do this all the time and you don’t necessarily need to log according to the strands either. Simply use the logs you have and go through them with the four strands in mind. When reading, are you making sure that most of it is meaning-focused? Are you doing enough fluency development for writing, or are you spending too much time writing things where you have to look up words every single sentence? Are you keeping language-focused learning to below ¼ (preferably much less)?

Beginners who want more hands-on help here might want to check out Unlocking Chinese: The ultimate course for beginners, where I teach everything you need to kickstart your Chinese learning, including how to build a routine using the above principles.

Finally, I would like to say that logging can be very powerful. While I haven’t done a systematic review of the literature, goal setting and logging progress are generally thought to increase how much people get done significantly. Looking back at my own life, this is very obviously the case.

If you’ve read this far, you are probably quite interested in progress tracking, albeit not necessarily in the same way as I am. Why don’t you leave a comment below and let me and others know what you think?

In the next article, we will look at specific tools and resources for logging your language learning. keep reading here:

Chinese language logging, part 3: Tools and resources for keeping track of your learning

References

Pigada, M., & Schmitt, N. (2006). Vocabulary acquisition from extensive reading: A case study. Reading in a foreign language, 18(1), 1-28.

Nakanishi, T. (2015). A meta‐analysis of extensive reading research. Tesol Quarterly, 49(1), 6-37.

Nation, P. (2007). The four strands. International Journal of Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 1(1), 2-13. Available here.

Tips and tricks for how to learn Chinese directly in your inbox

I've been learning and teaching Chinese for more than a decade. My goal is to help you find a way of learning that works for you. Sign up to my newsletter for a 7-day crash course in how to learn, as well as weekly ideas for how to improve your learning!

3 comments

“In the next article, we will look at specific tools and resources for logging your language learning. Stay tuned!”

Are we still planning on writing this article?

I’m really waiting for it….

Oh, yes! I’m just worried that people who aren’t that into logging will find it a bit boring to have three articles about the same topic clustered together. I don’t know exactly when I will write, it but I certainly haven’t forgotten about it. July, maybe?

The article you asked for is now live, including a fresh podcast episode as well. You can check them both out here: Chinese language logging, part 3: Tools and resources for keeping track of your learning