Measuring language ability is notoriously difficult, but can be important. It’s difficult because it’s hard to nail down what “language ability” is and how to measure it. Even if all aspects could be measured, this would be time-consuming and expensive.

Measuring language ability is notoriously difficult, but can be important. It’s difficult because it’s hard to nail down what “language ability” is and how to measure it. Even if all aspects could be measured, this would be time-consuming and expensive.

Figuring out how good your Chinese important for many reasons. For example, you might need to prove that your Chinese is at a certain level as indicated by a certain exam to be able to apply for a job or a university programme.

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to this article:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcast, Overcast, Spotify and many more!

But even if achieving a certain qualification is not your primary goal, it’s still important to pin down how good your Chinese is, because it can inform your choices about what to study next and how to go about it.

This is true within skills as well, so if you know that you need to improve your pronunciation, but that your initials and finals are okay, you should of course focus on tones. Furthermore, if you invest a lot of effort into learning something, but subsequent testing shows you’re not improving, maybe you need to look for other methods.

While you can base these decisions on your gut feeling, trying to anchor your judgement in a more rigorous framework can be helpful. In this article, we’re going to look at evaluating how good your Chinese is, not because you need to pass an exam, but because it will help you reach your goals, whatever they are.

B2 or better than last month

There are many ways of answering the question of how good your Chinese is, and all of them are fraught with problems. Naturally, if we want to do anything useful with the answer, it needs to be more detailed than “pretty good” or “almost fluent”; that simply won’t cut it.

There are two ways of answering the question:

- In absolute terms, with reference to a standard of some kind. The goal here is to see how your own ability relates to specific criteria and descriptors created by organisations that attempt to standardise assessment of language ability. Common standards are CEFR, ACTL and ILR.

- In relative terms, with reference to yourself at a previous stage. The aim of this assessment is mainly to see if you have improved in an area you’ve been working on, which lets you know if your doing the right thing. It’s also great for motivation and confidence. This is essentially the same as benchmarking, which I’ve written about before.

Since I have already written about the second type of assessment, I will focus on the first in this article. We’re going to look at two types of assessment, one in which you subjectively grade your own ability based on a set of questions or criteria, and one where you use various tools and resources to try to figure out what level you’re at.

Self-assessing language ability

Before we go into how to assess your own Chinese ability, it’s worthwhile to dwell on the question of whether self-assessment is meaningful. Are people in general able to accurately gauge how good they are in various areas of language proficiency?

The answer is a hesitant yes, but not very accurately. In general, lower level students tend to underestimate their language ability and higher level students tend to overestimate theirs. It also seems that self-assessment is most accurate for reading and least accurate for speaking.

I spent a few hours reading various studies regarding the validity of self assessment, which highlighted the difficulty of assessment in general. See the reference at the end for more reading, but the results in this section come from Engelhard and Pfingsthorn (2013), who basically conclude that self-assessment certainly has some predictive power, but not enough that they think it can replace other kinds of testing for the purpose of level placement.

Battle-tested, reality-oriented language proficiency

One obvious danger when assessing your own Chinese level is that you base your assessment not on real-world, proved performance, but on a more abstract or narrow definition of proficiency, such as measured by tests and grades. Many university courses in Chinese around the world don’t base grades on speaking ability and interaction at all, and if they do, written exams still make up the majority of students’ grades.

This sword cuts both ways, of course. If you’re really good at communicating with a limited number of words, are good at reading other people’s expressions and are a good communicator, you can handle many real-world situations in Chinese, while still failing your university course or score really low on proficiency tests like HSK and TOCFL. On the other hand, it’s also possible to get full marks in class and score very well on these proficiency tests, but still struggle even with basic interactions with native speakers. I wrote more about this problem here: Why your Chinese isn’t as good as you think it ought to be.

To make sure you’re not focusing only on a narrow set of skills promoted by a certain institution, make sure you rely on real-world language performance when assessing your ability. That’s what will allow you to talk with people, read books, chat with friends and watch TV series. Or whatever your goal for learning Chinese is.

Self-assessment with can-dos according to CEFR

Let’s assess our Chinese ability, shall we? The European Centre for Modern Languages (ECML) provides, among other things, a simple self test you can complete in minutes. Naturally, this might be too broad for your needs, but it can still be a fun exercise to do every few months as you level up your Chinese.

Self-evaluate your language skills

You will first be presented with a slider, indicating your general ability. This slider goes from 1 to 10, where 10 means very good (think educated native speaker) and 1 means beginner. The only function of this step in the test is to limit the number of questions so if you’re fairly advanced, you don’t have to answer questions meant for beginners. Just pick something, but it doesn’t hurt to choose a lower number here.

You will then be presented with questions regarding each of these five areas:

- Listening

- Reading

- Spoken interaction

- Spoken production

- Writing

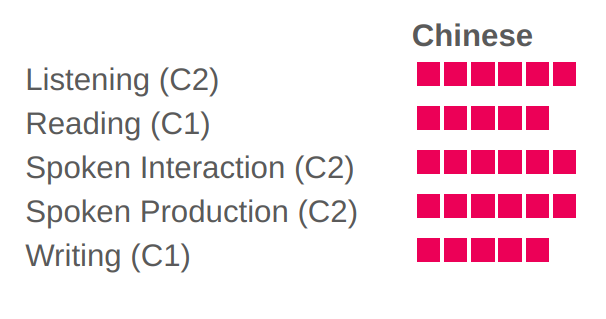

And your answers will place you on one of the levels A1, A2, B1, B2, C1 or C2. For more about CEFR (Common European Framework of Reference for Languages; read more here if you are unfamiliar with this standard, which is used widely beyond Europe as well).

How did it go? Did your result match your expectations? I would be delighted if you shared your experience in the comments! I have put a lengthy discussion of my own self-assessment as the top comment.

Resources for testing your own Chinese

The self-assessment above can be used for any language, of course, because it relies on your own judgement of your ability, not a real test of it. It is outside the scope of this article to go through in detail all the various tools available for testing your own Chinese, but I will give you a few examples to play with.

When using these resources, keep in mind that they only test a sliver of your actual language ability. A real proficiency test done by professionals takes time and money; no online tool or test can replace something like that. Even the widely used tests like HSK and TOCFL only test a limited range. Take the results with a pinch of salt.

I have not included resources that cost money here, but you can of course hire a teacher to assess your language ability. Please note that this kind of assessment requires that the teacher has certain training in the area you’re interested in. Anyone can give you a rough idea, but few can give you a detailed breakdown.

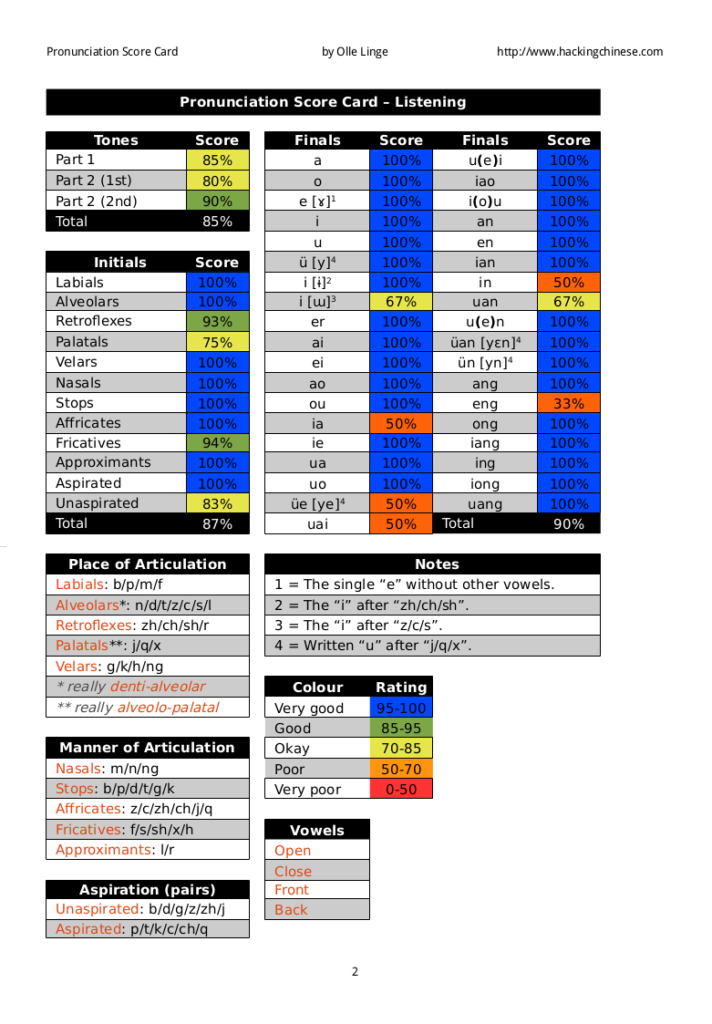

For example, I occasionally run pronunciation assessments here on Hacking Chinese, but I wouldn’t offer assessments on writing or reading, because that’s not my area of expertise. I do that regularly within the scope of courses I teach, of course, but that’s completely different from a stand-alone proficiency assessment.

For example, I occasionally run pronunciation assessments here on Hacking Chinese, but I wouldn’t offer assessments on writing or reading, because that’s not my area of expertise. I do that regularly within the scope of courses I teach, of course, but that’s completely different from a stand-alone proficiency assessment.

Proficiency tests

- HSK is the most widely used proficiency test for Chinese. You can download both reading and listening test for free from the official website. If you complete these under the same conditions as the real test (especially in the allotted time), you can use this as a gauge of reading and listening ability. Please note that the CEFR reference on that website is not in line with independent assessments (see this article on Wikipedia for an overview)

- TOCFL is the go-to proficiency test for Taiwan and traditional characters. Similarly, you can download mock tests from their website, and if you complete them according to the instructions, they should give you a good indication of your reading and listening ability.

Chinese specific test tools

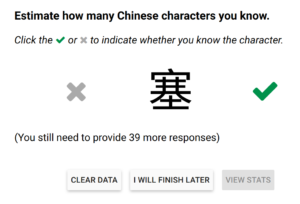

How many characters do you know? This neat test over at WordSwing lets you check how many Chinese characters you know. It is self-graded, so depending on what standard you use for answering, you can check how many characters you just recognise, how many you can pronounce or how many you know how to use. Note that you can check the pronunciation and meaning by clicking on the character (the info shows up in the bar at the bottom of the screen).

How many characters do you know? This neat test over at WordSwing lets you check how many Chinese characters you know. It is self-graded, so depending on what standard you use for answering, you can check how many characters you just recognise, how many you can pronounce or how many you know how to use. Note that you can check the pronunciation and meaning by clicking on the character (the info shows up in the bar at the bottom of the screen).- Basic tone test and tone course (free) – I’ve built a tone training course that first tests you and then trains you on single tones, also over at WordSwing. This is rather limited at the moment, because tones are about much more than single syllables, but it’s a good place to go if you struggle with basic tones.

I will update this list as I find more tools. If you know of any good ones I should add, please let me know! For example, I have tried to find a good tool that tests Pinyin, but most of them use common words you might have studied, which tests your vocabulary more than it tests your ability to identify sounds. Please leave a comment if you know of good tools for figuring out how good your Chinese is!

How to improve

If you’ve identified an area you want to work on, please check the following pages here on Hacking Chinese. They go through the basics and then points you to further reading:

References

Engelhardt, M., & Pfingsthorn, J. (2013). Self-assessment and placement tests–a worthwhile combination?. Language Learning in Higher Education, 2(1), 75-89.

Mistar, J. (2011). A study of the validity and reliability of self-assessment. Teflin Journal, 22(1), 45-58.

Stansfield, C. W., Gao, J., & Rivers, W. P. (2010). A concurrent validity study of self-assessments and the federal Interagency Language Roundtable oral proficiency interview. Russian Language Journal/Русский язык, 60, 299-315.

Tips and tricks for how to learn Chinese directly in your inbox

I've been learning and teaching Chinese for more than a decade. My goal is to help you find a way of learning that works for you. Sign up to my newsletter for a 7-day crash course in how to learn, as well as weekly ideas for how to improve your learning!

2 comments

I asked you to self-assess how good your Chinese is, so I’ll go ahead and show my own assessment!

I set the slider to 8, which gave me questions for C1 and C2, which is where I think my Chinese is at. The tool doesn’t tell you this until you show the results at the end, but if you’re unsure, choose a low number! Below, I show my own reasoning for C2 (I would answer “yes” to all C1 questions, so not terribly interesting).

Listening (C2): “I have no difficulty in understanding any kind of spoken language, whether live or broadcast, even when delivered at fast native speed, provided I have some time to get familiar with the accent.”

Provided that we take “accent” to mean 口音 and not 方言 (and we should), I can do these things. My main problem with listening is that I haven’t spoken with enough people with heavy accents, which is a hurdle when speaking with people from areas I’m not familiar with, but there’s room for this in the description above. I hesitated before answering “yes” here, because it does also matter what kind of content there is. I can listen to a lecture in linguistics without problems, but if I’m thrown into a rapid news broadcast with audio only and little context, it might be hard before I figure out what it’s about. Maybe answer “yes” here is an overestimation of my ability, but it’s hard to say without actually testing it.

Reading (C2): “I can read with ease virtually all forms of the written language, including abstract, structurally or linguistically complex texts such as manuals, specialised articles and literary works.”

While I can read the texts mentioned above, it’s a stretch to say that I can do it “with ease”. I haven’t read enough books to do that, maybe a hundred or so in total. I have to answer “no” to this question.

Spoken interaction (C2): “I can take part effortlessly in any conversation or discussion and have a good familiarity with idiomatic expressions and colloquialisms. I can express myself fluently and convey finer shades of meaning precisely. If I do have a problem I can backtrack and restructure around the difficulty so smoothly that other people are hardly aware of it.”

I have been through grad school in Chinese and teach courses in Chinese, for Chinese teachers. I need to backtrack and restructure sometimes, but can usually do so without trouble. I still make occasional mistakes, of course.

Spoken production (C2): “I can present a clear, smoothly flowing description or argument in a style appropriate to the context and with an effective logical structure which helps the recipient to notice and remember significant points.”

Yes, I feel I can do all this and have done so many times.

Writing (C2): “I can write clear, smoothly flowing text in an appropriate style. I can write complex letters, reports or articles which present a case with an effective logical structure which helps the recipient to notice and remember significant points. I can write summaries and reviews of professional or literary works.”

This is harder. I can certainly write clear, flowing text in an appropriate style, but “smoothly flowing” seems like a stretch. The rest of the requirements for C2 are okay, I think, although “complex letters” is a bit specific to Chinese. I have not even tried to master officialese (公文) and have no interest in learning how to write formal letters properly. With this in mind, I answer “no” here and put my writing at C1.

Really nice article. I also agree that HSK is not necessarily a reliable indicator of Chinese language ability. I know people who have passed HSK at a high level, yet still struggle when it comes to real conversations. I thought for a while about taking the HSK to gauge my own level but I think I have already found most of the holes in my ability, which I am working to patch up!