Learning how to read Chinese is a unique experience, quite unlike learning to read any other language. For that reason, students also face several unique challenges that are difficult to deal with relying only on strategies learnt from other languages. If you think that learning to read Chinese is like learning to read most other languages, you’re going to be both frustrated by the slow progress and constantly confused since reality doesn’t meet your expectations.

Learning how to read Chinese is a unique experience, quite unlike learning to read any other language. For that reason, students also face several unique challenges that are difficult to deal with relying only on strategies learnt from other languages. If you think that learning to read Chinese is like learning to read most other languages, you’re going to be both frustrated by the slow progress and constantly confused since reality doesn’t meet your expectations.

The goal in this article is to explain the most important challenges related to Chinese reading, so that you’ll be able to understand them and find ways to overcome them. Learning to read in Chinese is certainly possible, and some things can make the journey much smoother. Let’s have a look!

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcast, Overcast, Spotify and many other platforms!

Six challenges students face when learning to read Chinese

Let’s have a look at what challenges you’ll face when you set out on your journey to become literate in Chinese. Most of these are more important for beginners, but several of them will persist to a more advanced level. The issues discussed below are loosely based on Everson (2009).

Here’s an overview of the challenges:

- Challenge #1: Chinese is not alphabetic

- Challenge #2: Understanding how Chinese characters work

- Challenge #3: Chinese reading is not an isolated skill

- Challenge #4: Exposure and experience are important but elusive

- Challenge #5: Reading is about more than the text itself

- Challenge #6: Authentic Chinese texts are hard

- Conclusion: You can learn to read Chinese

Reading challenge #1: Chinese is not alphabetic

Unless you haven’t started learning Chinese yet, you probably know that the characters don’t make up an intricate alphabet. Yes, there is Pinyin, but that’s just a way to show how the characters are pronounced, using the Latin alphabet. Characters can contain components that hint at their pronunciation, but the link between the spoken and the written language is weak.

Considering that there are many thousands of characters in common use today, but that there is only around a thousand commonly used syllables (including tone variation), it should be clear that characters don’t represent sounds of entire syllables either, like it does in some other languages (Japanese hiragana and katakana, for example). We can also see that three are dozens of common characters that share the same pronunciation (shi or yi for example), so there’s clearly more to characters than what’s going on in any phonetic writing system.

What does this mean for you as a student?

It means that learning the writing system itself will take much longer than learning other writing systems that are phonetic, which include many other languages that are considered difficult, such as Korean, Arabic or Russian.

The reason is simple: While other languages require you to learn a few new symbols, maybe an entirely new alphabet (Russian), maybe even with tricky variations of letters (Arabic) or other complex ways of combining symbols (Korean), but the number of symbols is still limited to well below a hundred. In comparison, you need maybe 3,500 characters to be able to read normal text in Chinese.

In addition, since the characters are not directly linked to the spoken language, extra effort is needed to learn and retain the ability to read and especially to write them by hand. In most other languages, there’s natural reinforcement between listening and reading once you’ve figured out the sound system and spelling rules. Still, listening is important for reading ability in Chinese as well (see challenge #3 below).

How can you as a student overcome this challenge?

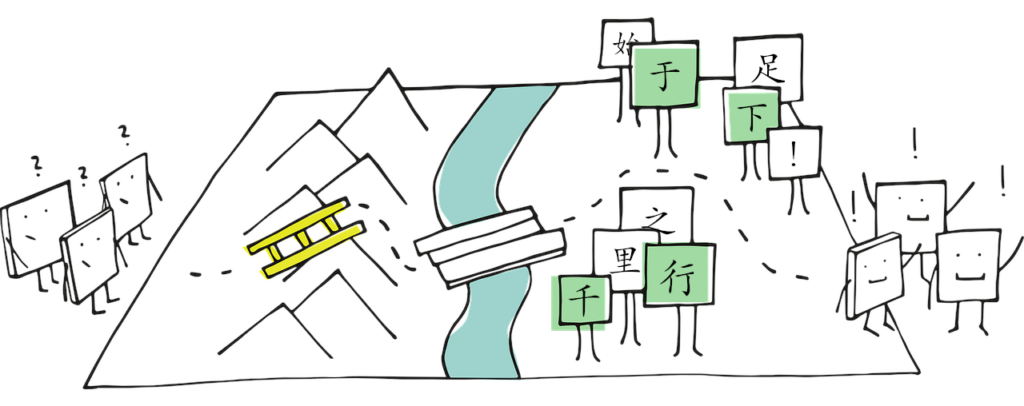

You can’t change the way the Chinese language works, but you can choose how to approach learning to read. Mentally, it’s good to be prepared for the fact that it will take time to learn characters, but that not just possible, but realistic provided that you consistently put in the effort required. Learning to read Chinese is a fascinating journey, so while the road can feel long at times, it also goes through a extraordinarily beautiful landscape! Enjoying the journey itself is more than just a cliche.

You can also choose what to focus on and what to leave for later, so an important question is how much to focus on handwriting, which is considerably harder than just reading, and not strictly necessary for learning how to read.

It’s also good to be a bit selective with what characters and words you learn early on, because the most common ones help you improve much more than rarer ones. Still, the best way to make the writing system easier is to really understand it, which is what the next challenge is about!

Reading challenge #2: Understanding how Chinese characters work

We have already established that the writing system isn’t phonetic, so the natural follow-up question is of course to learn how Chinese characters work. What are they? Just jumbles of strokes? Pictures? Something else?

There is in fact no single answer to that question, because there are many different types of characters. Some started out as pictures directly representing objects and concepts (such as 火 being a pictograph for “fire”), but most are combinations of components with different functions: some provide information about the meaning, some hint at the sound (characters like 妈 can’t be understood without taking sound into account).

What does this mean for you as a student?

As a beginner, it’s important to realise that understanding characters is really important for the simple reason that learning something you don’t understand is very hard, practically speaking impossible for adult foreigners. This is true for learning in general, not just Chinese characters, of course. Learning to combine a few hundred common components in often logical ways is much easier than learning thousands of complex and seemingly arbitrary symbols. I’ve been learning Chinese for well over a decade now and the characters I forget are those whose structure I don’t really understand.

How can you as a student overcome this challenge?

Fortunately, understanding characters make them much easier to learn and remember. Explaining how characters work is beyond the scope of this article, but I have written a series of articles that goes through the writing system from the smallest building blocks up to compound words, and you can check out the first article here: The building blocks of Chinese, part 1: Chinese characters and words in a nutshell. If you’re new to learning Chinese, or if you’ve studied for a while but still think that Chinese characters are pictures, don’t know how sound components work or how to learn characters effectively, this series is essential!

The building blocks of Chinese, part 1: Chinese characters and words in a nutshell

Reading challenge #3: Chinese reading is not an isolated skill

It’s tempting to think that since the link between the spoken language and Chinese characters is only indirect, learning to read and write are skills separate from learning to listen to and speak the language. This is not the case, however, and native speakers are obviously fluent in the spoken language when they start learning how to write. And it still takes them longer to learn that it takes us to learn alphabetic writing systems.

Spoken language is natural and something we typically learn automatically, but the written language is artificial and something we have to make concentrated effort to learn. One way of putting it is that the spoken language is the real deal, whereas the written language is just a way of noting it down, a bit like the notes for musical piece or the notation for dance choreography. The point is clearly the music and the dance, not their written forms. It follows then that trying to learn the written language without having at least a foundation in the spoken language will be hard. Maybe not impossible, but certainly unnecessarily difficult.

What does this mean for you as a student?

For various reasons, many courses and programs insist on students learning to read characters from the very beginning, which means they have no grasp of how the language works before they are asked to learn how it’s written. This is problematic for a number of reasons, some of which I outlined here: Should you learn to speak Chinese before you learn Chinese characters? The short answer is “yes, if you can, but how much you delay writing is up to you”.

Should you learn to speak Chinese before you learn Chinese characters?

If you are enrolled in a course or use a standard textbook, it’s likely that you will be asked to learn to read everything you can listen to, and learn to write everything you can say. By focusing on everything at once, progress will be very slow and since you lack the foundation in the spoken language, learning to read will be slower as well. If you are required not just to be able to read all new words, but also to write them by hand, you will progress at a snail’s pace.

Please note that many Chinese teachers,especially more traditionally-minded ones, will insist that learning characters is essential, but they forget that they themselves spent many years with the spoken language before they started learning characters. There seems to be a strong distaste for phonetic transcription, such as Pinyin, and a belief that it’s not real Chinese. Working with professional development for Chinese teachers, this is a view I’ve come across many, many times.

How can you as a student overcome this challenge?

If you are enrolled in a course, don’t count on your teacher providing you with everything you need. Try to focus as much as you can on listening in order to build up a general feel for how the language sounds and works, especially the sound system. It might be hard to avoid characters entirely, but see if you can get away with just learning the most important ones.

If you’re learning on your own or have more control over what you learn, focus on the spoken language first and delay learning characters a bit (see above). Learning some important or interesting characters here and there is fine, but you shouldn’t spend a majority of your time with the written language until you have a solid foundation in the spoken language. It’s hard to say for me for how long you should delay learning the written language, but as long as you feel comfortable with and is practically possible. That might be a week or years depending on the situation!

I should also say that preferences matter here, so if your sole motivation for starting to learn Chinese is to get to know the beautiful characters, then of course you shouldn’t delay doing that! I’m talking from a holistic perspective here, pointing out that learning to read will be harder if you don’t have a foundation in the spoken language.

Reading challenge #4: Exposure and experience are important but elusive

Successful reading requires different kinds of processing:

- Bottom-up processing allows you to decode characters and words, segment sentences into words (which is made significantly harder by the fact that Chinese has no spacing between words) and build up a emergent model of the intended message.

- Top-down processing draws on prior knowledge, logic deduction and other higher-order strategies to interpret, extrapolate and understand what you’re reading. Many strategies here are the same or similar regardless of language, but not all.

Both these types of processing require extensive exposure to the language to become automated and efficient. The more your brain needs to connect meaning and written symbols, the better you’ll get at and the faster the process will become. The more you utilise strategies to figure out meaning based on context and prior knowledge, the more you’ll be able to understand.

What does this mean for you as a student?

The main problem is that most students, not just beginners, read too little. I don’t necessarily mean that you don’t spend enough time reading, I mean that if you sum up the total number of characters in the texts that you read, the total number is too low. If you only do what your course requires of you, you will spend a lot of time with just a few relatively difficult texts. This doesn’t allow you to automate the reading process because you don’t get enough practice connecting written symbols to meaning.

If pursued for long enough, this will lead to a kind of pseudo-advanced level where you can only read what’s in your textbook and struggle to read any authentic texts (more about authentic texts in challenge #6 below). As a result, your reading speed will also be agonisingly slow, which is a problem in general, but on proficiency exams such as the HSK and TOCFL in particular.

How can you as a student overcome this challenge?

As a pure beginner, getting enough exposure and building experience by reading easier texts is impossible because there are no easy texts when you start from scratch. However, once you have gone through a few chapters in a textbook and know maybe 50 characters or so, there are a few things you can do to increase the amount of text you see without making it much harder.

You can rely on carefully written resources aimed at beginners that use sentences that intentionally use only characters you have studied. This is the approach I use in the sentence pack that comes with Unlocking Chinese, my beginner course, although there’s far from enough text there to cover your needs. Such resources need to be tailored to you individually or to the particular learning materials you’re using.

You can rely on carefully written resources aimed at beginners that use sentences that intentionally use only characters you have studied. This is the approach I use in the sentence pack that comes with Unlocking Chinese, my beginner course, although there’s far from enough text there to cover your needs. Such resources need to be tailored to you individually or to the particular learning materials you’re using. You can use more than one textbook, but start from the very beginning in the additional textbooks and just read the dialogues; they are likely to contain mostly things you already know. I wrote a separate article about the merits of using this strategy here: Why you should use more than one Chinese textbook

You can use more than one textbook, but start from the very beginning in the additional textbooks and just read the dialogues; they are likely to contain mostly things you already know. I wrote a separate article about the merits of using this strategy here: Why you should use more than one Chinese textbook You should start looking at the easiest graded readers once you know a hundred character or so, which will allow you to read longer stories without constantly peppering you with new characters. The Mandarin Companion breakout level is meant for students who know around 150 characters, for example. I have surveyed and presented easy, free reading materials here, and some more ideas for what to read as a beginner, including some paid, here.

You should start looking at the easiest graded readers once you know a hundred character or so, which will allow you to read longer stories without constantly peppering you with new characters. The Mandarin Companion breakout level is meant for students who know around 150 characters, for example. I have surveyed and presented easy, free reading materials here, and some more ideas for what to read as a beginner, including some paid, here.

The goal should be extensive reading, which I’ve written about in detail here:

Reading challenge #5: Reading is about more than the text itself

Above, I mentioned top-down processes for reading, but didn’t comment on them. Essentially, top-down processing is about using information that is not contained in the text you’re reading, or using other higher-order strategies such as deduction, extrapolation or interpreting to figure out what something might mean.

When it comes to information not contained in the text, writers (and speakers, of course, this is true for listening too) assume that you know certain things. Some of this information is culture-specific, which means that without the proper knowledge of Chinese language and culture, you might read a text and understand every word in it without actually understanding the message.

I use “culture” in a very wide sense here, including how people live, act, think and behave. An example might be if you read a dialogue where A leaves a location and B says 慢走 (màn zǒu), “walk slowly”, which is not a literal instruction to walk slowly, but rather a way of saying good-bye and telling them to take care. There are innumerable situations where things are expressed differently in Chinese and if you just understand the surface meaning of a word, you might miss the intended meaning.

In addition to this, texts might required background knowledge in history, pop culture or current events to make sense. When you read authentic texts in Chinese, the intended audience is a native speaker who knows much more than you do about these topics, so some references might swoosh by and make the text incomprehensible.

What does this mean for you as a student?

Most importantly, it’s normal to be able to read all the words in a sentence without understanding what the sentence means; it happens to all of us, not just beginners. In fact, it might happen less often to beginners because textbooks and other materials written for beginners will annotate or comment on things like this. While there could be grammatical reasons you don’t understand the sentence, it could also be that there’s some cultural reference that you’re missing.

How can you as a student overcome this challenge?

Books have been written about top-down reading strategies, so it would be unrealistic to try to summarise them here, but when you read in general, try to not to obsess about details in the language, but actively think about what you know about the context, the people involved, the location they are in and so on. Can you guess what the intended meaning is?

Form an hypothesis and keep reading. There is research to suggest that a tolerance towards ambiguity is beneficial for second language acquisition, meaning that students who are okay with not understanding everything and who are willing to keep going anyway usually do better than those who get bogged down in small details. When you’ve read the next sentence, maybe the previous sentence makes sense!

If you finish the text and return to the tricky passage but still have no clue what it means, your only way out is to ask someone who’s Chinese is much better than yours.

When it comes to background information about history, pop culture and current events, the only option is to read and listen a lot, not necessarily only in Chinese. It can make sense to study the basics of Chinese history and stay somewhat up-to-date with current events in English if your Chinese is not good enough to do this in Chinese yet. As you read and listen more, you will learn more about China and Chinese culture and gradually become better at understanding the intended message behind the characters and words. A fun way to do so is through cartoons!

Reading challenge #6: Authentic Chinese texts are hard

As we have discussed already, learning to read Chinese takes time; the contrast between reading a language close to your native language is huge. As a Swede, I can pick up a text in German and make sense of many of the words, although rarely the whole meaning, without even having studied German, and a Spaniard can learn to read Italian with relative ease simply by reading.

When learning Chinese, the benefit of reading authentic texts, here meaning texts that are not written specifically for language learners, is close to zero, unless they have been very carefully selected by a teacher. To read normal text (novels, newspapers, email), you need to know thousands of characters to even be able to do basic decoding, and if you can’t do that, reading this type of text has almost no benefits. It takes too much time.

What does this mean for you as a student?

For beginners and intermediate students, this means that you’re confined to texts written specifically for you, because these deliberately limit the number of characters and words to a manageable level, allowing you to read without having to look up five characters in every sentence. Focusing on easier reading materials allows you to actually enjoy reading and cover more text, which is beneficial for other reasons too (see above). Don’t expect to be reading novels or newspapers any time soon if you’re in your first year.

How can you as a student overcome this challenge?

There are many ways you can make authentic materials easier, and I wrote an article about how to scaffold your reading (and listening) here: 8 great ways to scaffold your Chinese listening and reading. In short, you can use pop-up dictionaries, spoken text, visualised text and various annotation tools to help you.

However, when the gap between your level and the level required to read the text without scaffolding is huge, none of these methods make much sense, and you’re much better off reading easier texts. One of the biggest mistakes I made when learning to read Chinese was that I didn’t understand this and spend countless hours trying to brute-force my way through texts that were much too difficult.

Conclusion: You can learn to read Chinese

All the above challenges can be overcome. Because the Chinese writing system isn’t phonetic, mastering it takes longer and requires different strategies, most importantly you need to understand how characters work in order to learn them effectively. In most cases, it also makes sense to focus on the spoken language first, because learning to read something you’ve already learnt in the spoken language is much easier and doesn’t require you to learn too many things at once.

You should also try to read as much as you can at a manageable difficulty level, rather than always push the limits and read challenging texts, which is what most textbooks and courses will make you do. This will help you automate bottom-up processes and also enable you to learn more about cultural aspects, even though that’s a challenge that will persist up to and including an advanced level. Stay away from authentic reading materials until you have enough vocabulary and reading experience under your belt to be able to tackle it without looking up every other character you read.

And finally, good luck!

References

Everson, Michael. (2009). Developing Literacy in Chinese as a Foreign Language. In Everson, M. E., & Xiao, Y. Teaching Chinese as a foreign language: Theories and applications. Cheng & Tsui.

Tips and tricks for how to learn Chinese directly in your inbox

I've been learning and teaching Chinese for more than a decade. My goal is to help you find a way of learning that works for you. Sign up to my newsletter for a 7-day crash course in how to learn, as well as weekly ideas for how to improve your learning!