I’ve taught many introduction courses in Chinese. Each time, I’ve felt the lack of a beginner-friendly list of the most common Chinese radicals. I tell students that learning character components is essential, and that it’s a long-term investment that will pay off several times over the course of their Chinese studies. I then show them some of the most common Chinese radicals.

But then what?

Beginners often find it hard to determine which components are common and which aren’t, and learning all of them at once is not a good idea. Sure, you can learn any component you see more than twice, but I think we can do better!

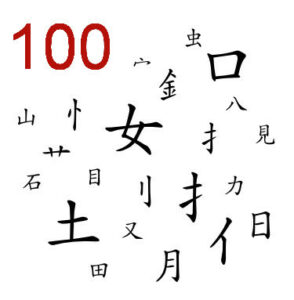

Filling a gap: The most common Chinese radicals

Lists of common Chinese radicals are typically based on data from a very large number of characters. If you base such a list on the 50,000 characters in the Kangxi dictionary, you will end up believing that 鸟/鳥, “bird”, is one of the most common Chinese radicals (the first character is simplified Chinese, the second is traditional Chinese; learn more here if you’re not sure what this means).

There’s only one problem: 鸟/鳥 is not even close to being the most important Chinese radical for beginners to learn.

If you only take the most commonly used 2,000 characters into account, 鸟 only occurs nine times. That means it doesn’t even make the top 100!

In other words, while there are many characters that use this radical, most of these characters are not within the most commonly used 2,000 and thus not relevant for beginners or even intermediate learners. In fact, most of the characters 鸟 appears in are bird names, which should be low on any beginner’s priority list.

The most common Chinese radicals among the most common characters

The list I have compiled here is based on the frequency of the radicals among the 2,000 most commonly used characters. This means that all these radicals are essential. Almost all occur in at least ten characters, most of them in more than that.

As a beginner, you can learn all the radicals on this list without fearing that you’re learning things you don’t actually need. It’s meant to be a solid foundation on which to build.

Download a list of the 100 most common Chinese radicals, completely free!

The list I have compiled is presented at the very end of this article (click here to skip to it). However, you probably want to download the list or do something else with it, so here are a few options:

- The 100 most common Chinese radicals as a PDF (suitable for printing). There are two PDF versions available, so if you don’t like that one (created by Markus Ackermann), you can try this version, made by Peter Lee. Thanks for helping me create the printable PDFs, guys!

- The 100 most common Chinese radicals in .txt format (for importing into other programs or for easy editing or viewing). If the Chinese characters are not displayed properly, try this file instead (the first is UTF-16, the other UTF-8).

- The 100 most common radicals in .anki format (this is the old Anki format, if you’re using a new version of Anki, you can just use this link, if you want better formatting of the cards, please refer to this text file, created by Gregory).

What information does the 100 most common Chinese radical list contain?

These are the columns used in the list:

- Simplified – The full form of the radical in simplified Chinese.

- Traditional – The full form of the radical in traditional Chinese.

- Variants – Common variants of the same character. While these may appear very different to a beginner, they are variants of the same character.

- Meaning – The basic meaning of the radical in English.

- Pronunciation – How to pronounce the radical in Pinyin. Pronunciations in brackets can be ignored! It means that these characters are mostly used for their meaning and seldom used on their own. Even native speakers might not know the pronunciation of these and will use the colloquial name instead (the last column).

- Examples – Five examples chosen from the 2,000 most common (simplified) characters to show you the component in context. Please note that it might not be the radical in all these examples, but also that this is irrelevant from a learner perspective. See the discussion below radicals and character component for a longer explanation.

- Comment – Things worth noting about this radical, often highlighting similarities and differences with other radicals.

- Colloquial name – The name Chinese people use to refer to the radical. Beginners can ignore this, but learning the most common ones is necessary if you need to talk about Chinese characters in Chinese.

Kickstart your character learning with the 100 most common Chinese radicals

As a beginner, you can use the list to boost your understanding of Chinese characters. Learning these 100 fairly simple characters will enable you to recognise parts of almost any character you will encounter. Of course, you won’t recognise all parts of every character, but it is a good start!

If you want a good tool to learn characters in general, I suggest using Skritter. It’s the only tool that gives you instructive feedback and requires you to write correct characters. It also uses spaced repetition, making learning characters much more efficient. If you want to study this radical list on Skritter, you can find it by clicking here.

If you want a good tool to learn characters in general, I suggest using Skritter. It’s the only tool that gives you instructive feedback and requires you to write correct characters. It also uses spaced repetition, making learning characters much more efficient. If you want to study this radical list on Skritter, you can find it by clicking here.

You can study this list in Skritter without even creating an account. If you do create an account, though, please use this link so you can get a hefty discount if you choose to subscribe. You have to sign up on the website to get the discount, but you can then use that account to study on iOS or Android.

Kickstart your understanding of Chinese characters

Chinese is a wonderful language to learn, partly because it can be hacked so efficiently!

Chinese is a wonderful language to learn, partly because it can be hacked so efficiently!

Learning Chinese characters by pure rote takes huge amounts of time, but by learning basic components (such as those in this list), you can make learning characters both meaningful and fun.

Instead of simply writing a character over and over, take a close look at the parts and find creative ways of linking them together.

I have written more about how to learn Chinese characters:

- How to learn Chinese characters as a beginner

- My best advice on how to learn Chinese characters

- Is it necessary to learn to write Chinese characters by hand?

- Is it necessary to learn the stroke order of Chinese characters?

- A minimum-effort approach to writing Chinese characters by hand

Most common Chinese radicals? Character components? Functional components?

This list isn’t perfect. In essence, there are two things that would make it even more useful. First, even though this list is weighted according to character frequency, it would be better to not just count occurrences, but to also weigh these. Thus, the 亻 in 他, “he”, should count for more than the 亻 in 伪/僞, “false”, which is obviously much less common.

Second, radicals aren’t necessarily the most important building blocks. A radical is really just the part of a character under which that character is sorted in dictionaries. This means that there are other character components that are common, but which aren’t radicals. Furthermore, since each character has one and only one radical, many of them occur more often as semantic components in characters where they aren’t the radical.

There are also many other components that normally carry information about how a character is pronounced. In 妈/媽, the radical is 女, “woman”, which is clearly related to the meaning of the character. The other part 马, means “horse”, and is as clearly not related to the meaning of the character. It’s pronounced the same way, though, but with a different tone. If you want a more thorough explanation of how characters work, I’ve written a series of articles about that, starting here:

The building blocks of Chinese, part 1: Chinese characters and words in a nutshell

I hope you will find this list useful, and that with it, learning Chinese characters will be meaningful and interesting rather than confusing and frustrating!

Kickstart your character learning with the 100 most common Chinese radicals

Below, I have tried to squeeze the list into the format of this article. It’s not likely to look good on a small screen, so if you’re on your phone, either use one of the files/links provided above or switch to a computer.

| S | T | Variant | Meaning | Pinyin | Examples | Comments | Colloquial |

| 人 | 人 | 亻 | person | rén | 今仁休位他 | Note similarity with 八, which means eight. | 单人旁(亻),人字头(人) |

| 口 | 口 | mouth, opening | kǒu | 古可名告知 | Note similarity with 囗, which always encloses characters, and means enclosure. | 口字旁 | |

| 土 | 土 | earth | tǔ | 在地型城地 | Note similarity with 士, which has a longer upper stroke and shorter bottom one, and means scholar. | 提土旁 | |

| 女 | 女 | woman, female | nǚ | 好妄始姓安 | 女字旁 | ||

| 心 | 心 | 忄,⺗ | heart | xīn | 必忙忘性想 | 竖心旁(忄),心字底(心),竖心底(⺗) | |

| 手 | 手 | 扌,龵 | hand | shǒu | 持掌打抱押 | 提手旁(扌),看字头(龵),手字旁(手) | |

| 日 | 日 | sun, day | rì | 白百明时晩 | Note similarity with 曰, which is broader and lower, and means to say. Also note 白 which means white. | 日字旁 | |

| 月 | 月 | moon, month | yuè | 有服青朝明 | This radical is actually two: moon 月 and meat 肉, but in modern Chinese, they look the same in most cases。 | 月字旁 | |

| 木 | 木 | tree | mù | 板相根本林 | Note similarity with 禾, which means grain. | 木字旁 | |

| 氵 | 氵 | 水,氺 | water | shuǐ | 永泳海洋沙 | Note similarity with 冫, which means ice. | 水字旁(水),三点水(氵),泰字底水(氺) |

| 火 | 火 | 灬 | fire | huǒ | 灯炎焦然炸 | 火字旁(火),四点底(灬) | |

| 纟 | 糹 | 糸 | silk | (mì) | 纪纸累细绩 | 绞丝旁(纟),独立绞丝(糸) | |

| 艹 | 艹 | 艸 | grass |

cǎo |

花英苦草茶 | Note that when the radical is on top, the traditional variant has four strokes. | 草字头(艹) |

| 讠 | 訁 | 言 | speech | yán | 说讲识评试 | 言字旁(讠) | |

| 辶 | 辶 | ⻍ | walk | (chuò) | 迎通道这近 | 走之旁(⻌) | |

| 钅 | 釒 | 金 | gold, metal | jīn | 银针钱铁钟 | 金字旁(钅) | |

| 刂 | 刂 | 刀 | knife, sword | dāo | 分切初利刻 | Note similarity with 力, which means force. | 立刀旁(刂),刀字旁(刀) |

| 宀 | 宀 | roof | (mián) | 守家室字宅 | Note similarity with 冖, which means cover, and with 亠, which means lid. | 宝盖头 | |

| 贝 | 貝 | shell | bèi | 财贪货贸员 | Note similarity with 见, which means to see. | 贝字旁 | |

| 一 | 一 | one | yī | 三旦正百天 | 横 | ||

| 力 | 力 | power, force | lì | 力加助勉男 | Note similarity with 刀, which means knife. | 力字旁 | |

| 又 | 又 | right hand | yòu | 反取受左友 | 又字旁 | ||

| 犭 | 犭 | 犬 | dog | (quǎn) | 犯狂狗献猪 | Note similarity with 大, which means big. | 反犬旁(犭),犬字旁(犬) |

| 禾 | 禾 | grain | (he) | 利私季和香 | Note similarity with 木, which means tree. | 禾木旁 | |

| ⺮ | ⺮ | 竹 | bamboo | zhú | 笑第简筷算 | 竹字头 | |

| 虫 | 虫 | insect | chóng | 強独蛇蛋蚊 | Even though this radical means insect, it’s used for many organisms which aren’t insects according to our taxonomy. | 虫字旁 | |

| 阜 | 阝left | mound, dam | (fù) | 防阻陆院陈 | Note that there are two radicals which look like this. On the left, it means mound, dam, and on the right, it means city. | 双耳刀(左耳刀) | |

| 大 | 大 | big, very | dà | 天尖因奇美 | 大字旁(头) | ||

| 广 | 广 | house on cliff | guǎng | 店府度座庭 | Note similarity with 厂, which means cliff (i.e. without the house). | 广字旁 | |

| 田 | 田 | field | tián | 思留略番累 | 田字旁 | ||

| 目 | 目 | 罒 | eye | mù | 眼睛看相省 | Note that the horizontal version can also mean net. | 目字旁(目),四字头(罒) |

| 石 | 石 | stone | shí | 砂破碑矿码 | 石字旁 | ||

| 衤 | 衤 | 衣 | clothes | yī | 初被裁裤袜 | Note similarity with 礻, which means sign, show or spirit. | 衣字旁(衤) |

| 足 | 足 | ⻊ | foot | zú | 跑跨跟路距 | 足字旁 | |

| 马 | 馬 | horse | mǎ | 码驾骂驻妈 | 马字旁 | ||

| 页 | 頁 | leaf | yè | 顺须领预顶 | 页字旁 | ||

| 巾 | 巾 | turban, scarf | (jīn) | 市布帝帐帽 | 巾字旁 | ||

| 米 | 米 | rice | mǐ | 类粉迷粗糖 | 米字旁 | ||

| 车 | 車 | cart, vehicle | chē | 轮软军较输 | 车字旁 | ||

| 八 | 八 | eight | bā | 公分趴兵共 | Note similarity with 人, which means human, person. | 八字旁(头) | |

| 尸 | 尸 | corpse | shī | 尺局尾居展 | Note similarity with 戶, which means door, family. | 尸字头 | |

| 寸 | 寸 | thumb, inch | cùn | 寺尊对射付 | 寸字旁 | ||

| 山 | 山 | mountain | shān | 岩岛岁崗岔 | 山字旁(头) | ||

| 攵 | 攵 | 攴 | knock, tap | (pū) | 收改攻做政 | Note similarity with 夊, which means to walk (slowly). | 反文旁(攵),旧反文旁(攴) |

| 彳 | 彳 | (small) step | (chí) | 彼很律微德 | Note similarity with 亻, which means human, person. | 双人旁 | |

| 十 | 十 | ten | shí | 什计古叶早 | 十字旁(头) | ||

| 工 | 工 | work | gōng | 左江红巧功 | 工字旁 | ||

| 方 | 方 | square, raft | fāng | 放旅族仿房 | 方字旁 | ||

| 门 | 門 | gate | mén | 间闲问闭闻 | 门字框 | ||

| 饣 | 飠 | 食 | eat, food | shí | 饭饿饮馆饱 | 食字旁 | |

| 欠 | 欠 | lack, yawn | qiàn | 欢欧欲次歌 | 欠字旁 | ||

| 儿 | 儿 | human, legs | ér | 元四光兄充 | Note similarity with 人, which means human, person, and with 八 which means eight. | 儿座底 | |

| 冫 | 冫 | ice | bīng | 冬冷冻况净 | 两点水 | ||

| 子 | 子 | child, seed | zǐ | 字学存孩季 | 子字旁 | ||

| 疒 | 疒 | sickness | (nè) | 病痛疗疯痩 | 病字旁 | ||

| 隹 | 隹 | (short-tailed) bird | (zhuī) | 雀集难雅谁 | 隹字旁 | ||

| 斤 | 斤 | axe | (jīn) | 所新听近析 | 斤字旁 | ||

| 亠 | 亠 | lid | (tóu) | 亡交京 | Note similarity with 宀, which means roof, and 冖 which means cover. | 点横头 | |

| 王 | 王 | 玉 | jade, king | yù, wáng | 主弄皇理现 | This radical is 玉, but when in composition, it looks like 王, king, and is probably more easily remembered like that. | 王字旁 |

| 白 | 白 | white | bái | 的皆皇怕迫 | Note similarity with 日, which means sun. | 白字旁 | |

| 立 | 立 | stand, erect | lì | 音意端亲位 | 立字旁 | ||

| 羊 | 羊 | ⺶,⺷ | sheep | yáng | 着样洋美鲜 | 羊字旁 | |

| 艮 | 艮 | stopping | (gèn) | 很恨恳根眼 | 艮字旁 | ||

| 冖 | 冖 | cover | (mì) | 写军农深荣 | 秃宝盖 | ||

| 厂 | 厂 | cliff | (hàn) | 厚原厉厅厕 | Note similarity with 广, which has ha house on top (the dot). | 厂字旁 | |

| 皿 | 皿 | dish | (mǐn) | 盆监盟盛盖 | 皿字底 | ||

| 礻 | 礻 | 示 | sign, spirit, show | shì | 社神视祝祥 | Note similarity with 衤, which means clothes. | 示字旁 |

| 穴 | 穴 | cave | xuè | 空突穷究窗 | 穴宝盖 | ||

| 走 | 走 | run, walk | zǒu | 起超越赶徒 | 走字旁 | ||

| 雨 | 雨 | rain | yǔ | 雷雪霜需露 | 雨字头 | ||

| 囗 | 囗 | enclosure | (wéi) | 回国因图团 | Note similarity with 口, which does not enclose other components and means mouth. | 国字框 | |

| 小 | 小 | ⺌⺍ | small | xiǎo | 少肖尚尖尘 | 小字旁(头) | |

| 戈 | 戈 | halberd | (gē) | 成式战感我 | 戈字旁 | ||

| 几 | 几 | table | jī | 朵机风凡凤 | 几字旁 | ||

| 舌 | 舌 | tongue | shé | 乱适话舍活 | 舌字旁 | ||

| 干 | 干 | dry | gān | 平刊汗旱赶 | 干字旁 | ||

| 殳 | 殳 | weapon | (shū) | 段没投般设 | 殳字旁 | ||

| 夕 | 夕 | evening, sunset | xī | 外多夜名岁 | 夕字旁 | ||

| 止 | 止 | stop | zhǐ | 正此步歪址 | 止字旁 | ||

| 牜 | 牜 | 牛,⺧ | cow | niú | 告物解特件 | 牛字旁(头) | |

| 皮 | 皮 | skin | pí | 披彼波破疲 | 皮字旁 | ||

| 耳 | 耳 | ear | ěr | 取闻职聪联 | 耳字旁 | ||

| 辛 | 辛 | bitter | xīn | 辜辟辣辨辩 | 辛字旁 | ||

| 阝right | 阝right | 邑 | city | (yì) | 那邦部都邮 | Note that there are two radicals which look like this. On the left, it means mound, dam, and on the right, it means city. | 双耳刀(右耳刀) |

| 酉 | 酉 | wine | (yǒu) | 醉酒醒酸尊 | 酉字旁 | ||

| 青 | 青 | green/blue | qīng | 请清情晴猜 | 青字旁 | ||

| 鸟 | 鳥 | bird | niǎo | 鸦鸣鸭岛鸡 | 鸟字旁 | ||

| 弓 | 弓 | bow | gōng | 引张弱第强 | 弓字旁 | ||

| 厶 | 厶 | private | sī | 公勾去私云 | 私字旁 | ||

| 户 | 户 | 戶 | door, house | hù | 所房炉护启 | Note similarity with 尸, which means corpse. | 户字旁 |

| 羽 | 羽 | feather | yǔ | 习翻翅塌扇 | 羽字旁 | ||

| 舟 | 舟 | boat | chuán | 般船航盘艇 | 舟字旁 | ||

| 里 | 里 | village, mile | lǐ | 野重量理埋 | 里字旁 | ||

| 匕 | 匕 | spoon | (bǐ) | 匙比北呢旨 | 匕字旁 | ||

| 夂 | 夂 | go (slowly) | (suī) | 各條复备夏 | Note similarity with 攵, which means to knock, to rap. | 折文旁 | |

| 见 | 見 | see | jiàn | 观规视现觉 | Note similarity with 贝, which means shell. | 见字旁 | |

| 卩 | 卩 | seal | (jié) | 卷印却即危 | 单耳刀 | ||

| 罒 | 罒 | 网 | net | wǎng | 罗罚罢罪罩 | Note that the horizontal version can also mean net. | 四字头(罒) |

| 士 | 士 | scholar | shì | 吉壶志声壮 | Note similarity with 土, which means earth. | 士字旁 | |

| 勹 | 勹 | embrace, wrap | (bāo) | 包勿勾勺勻 | 包字头 |

Tips and tricks for how to learn Chinese directly in your inbox

I've been learning and teaching Chinese for more than a decade. My goal is to help you find a way of learning that works for you. Sign up to my newsletter for a 7-day crash course in how to learn, as well as weekly ideas for how to improve your learning!

121 comments

Nice resource.

Your observation that “Chinese is a wonderful language to learn, partly because it can be hacked very efficiently,” is something that I find more and more true the more time I spend reading about it. I really which I had known all these strategies several years ago before I learned Chinese!

This is partly why I enjoy writing articles here on Hacking Chinese! I write about things I know now that I wish someone would have told me about years ago. If you have any particular hacks, don’t hesitate to share!

It’s “I wish someone HAD told me about years ago”, not “would have told me….”

Example of the correct usage: “If I HAD asked my friend, he WOULD HAVE told me years ago”.

Even though your version is definitely correct, I think both versions are acceptable. I searched a bit for similar sentences online and it seems like “I wish he would have told me” is acceptable in AmE, but in BrE, “I wish he had told me” is preferred. I’m not a native speaker, but I found several references to native speakers who find that “I wish he would have told me” is grammatical:

http://forum.wordreference.com/showthread.php?t=2762502

http://www.antimoon.com/forum/t3112-0.htm

Interesting point, though, I haven’t noticed this before. Since I try to stick to BrE in general, your comment definitely makes sense, thanks!

Hi Olle,

Thanks for your reply. I wouldn’t like to presume you weren’t a native speaker, even though your name doesn’t ‘sound’ American/British/Canadian, etc, without having it confirmed by you first. I’d guess that you’re Scandinavian of origin, perhaps Norwegian? Not sure, though.

I’m an English teacher – and, yes, I am from the U.K. I think that the ‘would have told (or other verb)’ may be deemed ‘acceptable’, as you state – perhaps by North Americans, perhaps by others, too -, but I’m pretty sure that, in a strictly grammatical sense, it is incorrect. The meaning is clear, through context, but it is not correct.

I’m not sure whether you watch football (‘soccer’ – eeekkk!), but many English footballers will say such things as, “He’s went in on goal” (He approached….), or “We was having a bad run recently” (‘were’), or, from my own region, near Liverpool, “Youse lot are a stronger team….” (‘You are a….’). These are acceptable as dialectal variations, perhaps, but are grammatically incorrect in terms of ‘standard’ English.

Thanks again, and congratulations on the Web-site. Most informative!

English is spoken correctly in many different countries. As such there are different dictionaries that apply to the US dialect, British dialect, ect.

Most languages actually have multiple different dialects and one might say it is a little over-reaching to say that there is only one correct version of a sentence.

I must agree with Danny. More so, because we’re on a website that’s purpose is to facilitate the teaching of a foreign language. Those studying other languages very often hear the term dialect.

Dialects may be easy to disregard if you’re just an English teacher, but while learning another language one cannot forget dialects and the fact that even popular mistakes can be given credit if they’re supported by a dialect.

After all, languages are a living thing, changing constantly and growing with each generation.

I don’t mean to say that proper English has no place, I just mean to say that both have a place.

God, what a frightful pedant you are.

Actually, he’s not a real pendant, just someone trying to pass off as intellectual. ”Wish + past perfect” is perfectly acceptable, sure, but ”wish + would + past participle” refers to ‘complaints’ regarding past events.

An exceptionally old conversation, but just a reminder that your usage is fine according to AmE with a recent horror movie trailer (0:09): https://youtu.be/1Vnghdsjmd0?t=8.

Thanking for making the effort and and giving this radicals list to us. I think it’s very useful for beginners to learn the radicals, something my first Chinese teacher (in Finland) never made us to do.

When learning characters, especially in the beginning, I also found MDBG dictionarys Character decomposition tool very helpful. (It’s inside the dictionary and doesn’t include all the characters, but many.)

Also thank you for adding the colloquial names of the radicals, that’s very helpful for me because I only know a few of the names.

I tried to download both links but I don’t have the program to read the first link and the font in the text link is partly corrupted or somehow partly unreadable: e.g. Âãπ Âãπ embrace, wrap (bao1) ÂåÖÂãøÂãæÂã∫Â㪠ÂåÖÂ≠ó§¥

Is there another way to download this list? Thanks.

I have added instructions for how to get the list to display properly. Your browser is probably trying to view this in a character set other than Unicode. If you use IE, right click and change encoding to unicode. In FF, go to view and then character encoding and change to Unicode. Other browsers should work the same way. If this doesn’t help, let me know! It really should work, though (it does for me on other computers).

OK I now have a folder of sever files on my desktop. And I just downloaded Anki. I am trying to figure out the correct file to Anki.

Great informative content as usual. I have some content / tools (e.g. frequency search) that might help you with this lists’s future plans. Send me a note.

Great website! Super inspiring, I absolutely love it! About the files, the anti file above downloads ok to my Android phone, but it seems to be a text file, not an anki file, and will not open with anki on my phone. Any idea why?

The easiest thing to do is download the deck from within Anki. It’s called “The 100 most common Chinese radicals”, you should be able to find and download it without problems. Let me know if this works, I just uploaded it.

Well said Olle. My college in the US forced intro level students to learn roughly sixty radicals during the first week. I hated it at the time since I thought they were essentially characters that I would never write, but it has improved my written Chinese immensely since. Unfortunately not all programs are like this, especially here in Taiwan.

Awesome Ollie! Thanks! I went the Shida route for six months a few years ago and realised there was a huge hole in the way that they taught characters to beginners. Decided recently to begin serious study again. Thought about the way that my kids talk about characters when they’re asking how to write something, and came to the conclusion myself that I need to learn radicals. Also came to realization by myself that all the radical lists I could find were radically flawed in some way or other. Have been learning the 214 from Wiki, but know that many of them are unnecessary to me, and many of the meanings given don’t match modern usage. So good to read this and find your list! THANKS!

Thank you very much for making a list of the most common radicals. I have downloaded the Anki format file from the link you provided, but for some reason I can’t see the whole radical. The right part of the radical is being cut off for some reason, so I can only see about 70% of it. Any idea what could be wrong?

This is almost definitely something wrong with the way Anki is configured rather than the list itself. I suggest you use the help provided here.

That link didn’t work for me.

It doesn’t for me either, so I’ve updated so that it now points to the main help site for Anki!

Here’s how I added Chinese Character support on a Mac:

https://chinese.yabla.com/type-chinese-characters.php?platform=mac

Basically these steps: System Preferences, Keyboard, Input Sources, Chinese Simplified, Stroke Simplified (Also check the box that says “Show Input menu in menu bar”

I hope this helps. Characters would not display when I downloaded my kids’ Chinese homework until I did this.

Hi Olle, first off thanks you SO much for all the help your site provides!

I have been going over the 100 most common radicals list you generously provided in Anki, and I have a quick question:

On some of the radicals, the tone, meaning, or even pronunciation that I have learned is not listed. For example on 厂, my tutor taught me chang3 – factory, but in the 100 most common radicals list it is han4 – cliff. On archchinese there is also no mention of han4, just chang3.

I was just wondering what the difference is and why you chose han4 (I am a beginner, this is a genuine question, not a “you are wrong” type of statement).

Thanks again for everything you’re doing for the community!

This is slightly complicated, but in essence, there are two 厂. One is the original radical, which is indeed pronounced han4, although my guess is that almost no-one uses that reading (that’s why it’s written within brackets). The radical is the original semantic part of the character. Then there is the simplified character 厂 (traditional: 廠), which is a character pronounced chang3 as you suggest. Your teacher taught you the character, not the original radical. They happen to look the same in simplified Chinese. However, you don’t need to know this. You don’t need to learn the pronunciation of any radicals unless they are also common characters, in which case you will encounter them in texts you read or language you hear.

References:

http://www.zdic.net/zd/zi/ZdicE5Zdic8EZdic82.htm

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kangxi_radicals

http://zhongwen.com/d/201/x68.htm

Thanks for that nice article! I stumbled upon it by googling for a way to find out, what radicals are used in a piece of vocabulary. I will go and try learning those radicals; my teacher already encouraged me to do that to improve my writing skills but by now I just couldnt overcome my laziness. It is so hard to invest into future learning and not just learn vocabulary right away. But I will definitely try now.

However I was not successful googling, so here is my question: How can I find out, what radicals are used in a character?

E.g. 空 has the radicals “mian” and “gong” in it. How can I be sure that the rest of the character is not a radical but just ornament? What I am looking for is a dictionary that shows me not only the translation for a character but also classifiers+radicals. Do you know of such a thing?

Ofcourse this is no important point – I can go on and learn radicals and after a while will recognize them in characters. That would just be a fun way for me to make things easier…

I posted a number of useful dictionaries in this article, several of them do what you’re after. I typically use Zhongwen.com (traditional) and Hanzicraft.

Wow, what a lightning-fast response! Thanks 😀

I’ve found something new that tries to order with respect to frequency as components in common characters. I can’t yet comment on how well it does it, but I’m using the ordered characters fruitfully…

http://www.learnm.org/decompE.php

That site appears to be offline. Any idea where it went?

Which site appears to be offline? Everything seems to work! Cool with the Wikipedia links. 🙂

Learnm.org in Bills link above returns a server not found for me.

As part of a new project I’m working on I took this list and put it on a web page here. Each radical links to its Wikipedia page as well.

Great article. I can see the importance of learning radicals. Any chance that someone has this in Pleco format?

Hi!

At first – thank You so much for giving me hope for learning chinese characters and actually REMEMBER them.

I used to wirte every single character like many times until lerning it by heart. I was all happy but then, after writing 50 more characters I realised I already forgot the first one. Then learning it again, then forgot. Vicious cycle.

I started using mnemonics techniques I found on Your site and it’s like I won the lottery:)

But for now – as a fresh Sinology student – I have to memorize ALL kangxi radicals(radical, meaning, number and pronunciation) and have no idea how to memorize them! Especially those which are not really useful and it’s hard to make up connotation between the character and it’s number(and pinyin).

Do You have any ideas?

And once again – thank You so much!

When it comes to the very basics, sometimes you just have to spend some time and write the radicals enough to commit them to memory. For instance, you might remember 火 because it actually looks a little bit like a flame, but it’s not a good idea to try to use mnemonics to learn how to write this. I generally don’t use mnemonics for very elementary parts, but use lots of mnemonics for combining these parts.

Well, I already know roughly 500 characters( traditional and their simplified version if they have one) so it’s not like 火 is not my close friend;) I was talking about not-so-popular ones like 掛號 for instance. I know the components but not all actual radicals in order… I need to remeber the exact list for my “chinese dictionaries” classes and i wanned advice on that;)

I think there must be some terminology confusion going on. A single character only ever has one radical and that’s the semantic part that is used to sort the character in dictionaries. It’s usually related to the meaning of the character (rather than the sound). So, if you take a word like 掛號, there are only two radicals and I don’t really understand what you mean by “radicals in order” and “the exact list”?

HI! the link to nciku doesn’t seem to be working… or is it just my computer?

Thank for notifying me, they must have changed their article structure or something. This link should work.

So grateful to have this list for our 101 days challenge! It’s so useful to systematically learn. Thank you!

Olle, thank you for sharing this list. It saves me so much time. Two things that can improve this deck even more is to :

1. Add another field that shares your tips on how to remember or associate that radical with the meaning in English. Many of the radicals look nothing like its meaning. (Hope I’m not asking for too much)

2. Improve the styling on the card. Espiecialy the font and font size used for the Chinese is not the best. I have attached my own styling that works well form me. It also makes it more customizable. Some users at Anki have complained about the Chinese font size without realizing that they can customize it themselves.

To use this styling at the Deck, click on [Browse], then click on [Cards …]

Editor’s note: Because of display problems, the code provided here has been moved to a separate text file.

Hi Gregory,

I definitely agree that the list could be improved. In fact, I have been thinking about doing something much more in-depth about character components which would actually be more aimed at learning characters rather than just listing the radicals. I don’t use Anki much at the moment and updating lists is a bit of a hassle in Anki (or it was last time I checked anyway), but I will update it next time I check through decks I share. In the meantime, I’ll include your instructions in the article so at least people who don’t know how to achieve that on their own can still get it to work. Thanks!

Hi Olle,

Just wanted to let you know that I had some fun with perl, awk and LaTeX, and created a nicely typeset PDF from your table of the most common radicals. All radicals and example characters are hyperlinked into http://www.archchinese.com.

The PDF and everything to recreate it is up on . I wasn’t sure about the license terms for your data. Would you be ok with CC-BY-SA (creative commons-attribution-share alike)?

Shoot, screwed up the markup…

The final PDF is here.

This is fantastic!

I have added your PDF to the main article along with another PDF provided by another reader (Peter Lee)!

That’s great! I don’t know enough about different licences to have an opinion, but as a link back to the original article is included, I’m fine! Thanks for providing this. 🙂

For those who use Skritter, I published these 100 radicals as a new word list:

Simplified

Traditional

Thanks! I had that on my to-do list, but it risked remaining there forever, so I’m really grateful you took the time to convert this to Skritter, I will definitely share!

Hey, this looks wonderful. I was wondering if there were anyway to get this as a file which is compatible with Pleco?

Hi,

What a lovely site! Härligt material!

I wonder as well as Andrew if there is any way to get this converted to Pleco! It would be great to have! I myself am not a wisard of Pleco but I love their flashcard system 🙂

Med vänlig hälsning,

Från Finland

Very useful tool. One question though: the font on Anki on my computer isn’t the best for reading characters. Anyone know how to change the font on the hanzi to make them easier to pick out component parts?

As a native Chinese speaker I have to point out a mistake in the 100-radicals-markus.pdf. It states that 罒 is a variant of 目, which is not true. The 罒 is in fact itself a variant of ancient Chinese character (now also used as the simplified Chinese character) 网, which means “net”. A good example would be the traditional Chinese character 羅, which is etymologically composed of “a net 网 on top, and some silk 糸 aside, to catch bird 隹”. Such usage is still kept in modern Chinese word 羅網(simplified 罗网), as in the idioms 天羅地網 and 自投羅網. Another example is 罩.

By the way, I have to point out that many native speakers are not able to pronounce many radicals whose pronunciation is given in brackets.

Hope all these would help you with learning Chinese. 🙂

Last year I studied Chinese and unfortunately, I was a bit lazy when it came to learning the meaning of the different radicals. Now, I really understand the importance of knowing radicals and their meanings. If you take the time to get to know key radicals, it makes the whole process of memorizing characters much much easier. Great Article !

Dear Olle Linge,

Thank you very much for your useful information always on this website. As a Japanese learner I am really learning a lot from your page. Especially articles that have to do with Kanji in general or language learning in general are very useful to me.

I had a question to which I have not been able to find the answer for a quite long time. Do you know any type of linguistics literature in which the ethymology of the Chinese radicals is explained? For example the radical 方 is a quite interesting one, because it can mean square or raft. Maybe it is just me, but to me it seems that square and raft are two COMPLETELY different things. However, from the ethymology I expect them to be quite related.

I had this with another Kanji radical which is 彳. The meaning of this radical is given as to go, (small) step, to stop, to wait. At first I was of course confused about this, just like in the example of square and raft, two completely different things. In here they seem even to be opposite. To stop and to go seem to be quite opposite to each other. I was thinking this until I researched the meaning of one of the other definitions which was to linger. It means to continue to exist. To stay too long at a certain place. So this means that the radical 彳 has the meaning of going or continuing in a certain existing state, which can be said as going on. So this clarified a lot to me, but I am still quite confused about a lot of the earlier radicals.

If you could help me to find a more extensive list with meanings and explanations of the Chinese radicals then that would really help. I have searched for this very long, but I cannot find it.

Hey there,

I wish I could use the 100 radicals on Anki but the link seems to be dead: https://ankiweb.net/shared/info/2438424285

Can anyone help?

Thanks

Franz

Hi,

I have updated the link, enjoy!

Best,

Olle

Hi Olle, I created an anki deck of phonetic characters (all the characters in the first table on hanzicraft http://www.hanzicraft.com/lists/phonetic-sets). Even though it doesn’t have audio (it would be amazing if anyone has done a list with audio?!) I thought it might be helpful to other people. See link to downloadable deck below.

https://ankiweb.net/shared/info/623579314

Hello,

could you also post an XLS (X) file with your radicals list (with separated columns), please?

Thanks for your wonderful website, I got also your book and after reading your reviews, I also subscribed to Skritter and Chairman Bao, hoping to improve my Chinese reading and writing skills (I live and work in China).

All best

Richard

Hi,

There is a text file that you could easily import into any spreadsheet program!

Best,

Olle

Thanks, I was only copying to Excel, which was why it would not separate properly, opening and converting made the job well. Thanks for your excellent job!

Thank you Markus!

Please note that the 100 radicals list for Skritter is now available here: https://legacy.skritter.com/vocab/list?list=5907881914531840

^Previous link was for the “Legacy” version of skritter. For skritter 2.0, just browse user-made lists or go here: https://skritter.com/vocablists/view/1060463001

Thanks! It would be great if Olle could update the link in the text!

Updated! 🙂

Chinese is a wonderful language to learn, partly because it can be hacked very efficiently

Are these radicals best learned more or less by rote? You seem adamant that people don’t waste their time trying to study by rote characters that they find particularly difficult, but find a mnemonic or find the radicals in said character, etc. Is there a good system for doing this with radicals? Hard to break down the basic pieces.

Rote is okay in this case, but a better way would be to study their origins. These are mostly semantic components referring to the meaning of the character, and they are also pictographs. You can seldom “see” what they mean, but looking at their development can make it easier to remember them!

You just gave my what I was looking for. Thanks a lot. You genius!!!

good article!

Hi!

At first – thank You so much for giving me hope for learning chinese characters and actually REMEMBER them.

What I miss, is whether a radical can be a character of is own, or is only a component and perhaps a shift in meaning from radical to character (like that you mentioned with 厂).

I miss the rest of the list too. To take your bird example. 鸟 is an important character of his own, but at least when learning 鸡 chicken, one should know the component and if it would be number 120 on the list, the list should reach so far. But perhaps there is a point better to decompose a new character with hanzicraft or characterpop to identify new radicalcomponents, when you reached a certain level and learn the radical at this point.

What I really miss, something about the components, that are not radicals. E.g. what is the left part of 那? Is it a part of other characters too or only a 那-thing? Which are other important components, perhaps composed of two radicals?

Hi Olle, I want to thank you for all the work you do to help people around the world to learn Chinese, I just ordered your book and I can’t wait to have it in my hands and start applying the principles written in it.

I also just started using this list to learn radicals with Anki, I would like to customize and publish a new version of the list with new styles, audio, and tones marked in the pinyin pronunciation, I think I can learn better that way, also I could install the updated list in my phone thanks to the Anki web.

Is okay with you if I publish a list based on yours? I would recognize you as the original author for sure!

Once again thanks for the work you do.

Glad you find my musings helpful! Yes, you’re welcome to create a list, but please link back to this article.

Hi Olle,

Firstly thanks for such a useful website!

This is an interesting list and for beginners it’s much more useful to be looking at radical frequencies in the most commonly used 2000 characters. I assume they are listed on your table in order of frequency? Have you published the actual frequencies anyway?

Thanks! Rachel

Yes, in order of frequency! I didn’t see much utility in including actual frequency here because it’s a very specific list made for a very specific purpose and I couldn’t envision much use for more detailed ranking than what radical is more common than another radical. I could check if I still have it somewhere, but what would you use it for? Let’s say we find that the first radical on the list is 1.5 times more common than the second one on the list, what would you do with that information? In all practical situations I can think of, the rank on the list will be more than enough!

Thanks Olle, that’s great. It’s for a game I’m developing for young novice learners. This information is actually enough for now so thanks very much.

hi Olle,

I just came across your wonderful site and would like to thank you for creating this radical list and the many other helpful articles and resources to help leaners of Chinese. I am a native speaker and also a teacher of Mandarin Chinese and have looked through your radical list (PDF version) and cross-checked with dictionaries and would just like to point out that the pronunciations of the radicals 彳and 舟 should be chi4 and zhou1 respectively as far as I can ascertain, and not chi2 and chuan2 as displayed on the list. The character 舟, whether on its own or as a radical, is never pronounced chuan2, which is the pronunciation of the character 船. It would be good if the list could be updated with the correct pronunciations of these radicals. Thank you again for your great work.

Thank you for pointing this out! I’m working on an updated version of this list and I will make sure to fix the pronunciation in the second round.

Olle, I’m hoping to start studying Mandarin in about six months (after I finish some other projects. As a head start, I will study these 100 radicals in my spare time. I intend to focus on Simplified characters.

My question to you… would you recommend I also lightly study the equivalent Traditional characters (less emphasis and no practicing writing)? Or do you recommend I act as if Traditional characters do not exist and solely focus on studying Simplified?

Either approach will work. Being familiar with traditional without really trying to study it (for example by recognising them without necessarily being able to write them by hand) is a good option, but it’s also something which becomes much easier once you know more about characters. You can definitely do without traditional entirely if you find it confusing, but on the other hand, if you find it interesting, then peeking at traditional while focusing on simplified should give you a better understanding!

Hey Olle, I am living now 10 years in shanghai (as long and old as this article) and speak only semi-fluent (that even a word?) mandarin. Speaking was never an issue for me. BUT…i was always (probably) too lazy (lets be honest) to actually seriously start to learn to read and write chinese characters, while relying on others to help or talking was just as sufficient. And now, after all those years i finally made the decision to learn solid reading and writing. What was always my fear, that i would still need another 10 years to exactly learn that (probably not that much). It is amazing how chinese characters still seem to appear like hieroglyphs to me, though i speak chinese quite well.

Then i came across your website. This is probably the best structured, understandable hence not confusing website about learning chinese characters i found so far! And the 100-character list is a milestone for me. I mean seriously! Thank you so much to get me motivated and onto the right track to SERIOUSLY learn to read and write Chinese! This PDF you included is gold for me!

Can you imagine…how i will feel, even after reading this list and studying the first day, walking through the streets of shanghai! Like adam, discovering he was naked after the first bite of the apple Eve gave her!

Thank you so much for this article (or page in general) there seems to be endless content here! I will definitly have a look at your skritter-course!

Greetings

Mark

–

PS: Any suggestions how i should go ahead after the common 100-most common radicals. As you described, discovering it my own way, through reading, while stumbling across new characters?

Hi Mark! Glad you find the website helpful. 🙂 I think characters are best learnt through reading, yes. There are graded readers (from Mandarin Companion, for example), that only use around 150 characters to tell stories. Try to get to that level and then read everything you can find. You can also check this article I published recently about reading material for beginners: The 10 best free Chinese reading resources for beginner, intermediate and advanced learners

Some of the example characters are incorrect, using the phonetic element instead of the radical. Example: 请. The radical here is 讠, not 青。

Yes, that is as intended, although it could be more clearly marked in the list itself. The goal here is to give people the building blocks they need to remember how to write characters, which means it’s useful to know what 青 means, even if it’s the phonetic component in those characters. Phonetic components are explained in the articles linked to above the list itself.

The problem here is that I’m using “radical” as a proxy for “semantic component”, simply because there isn’t an easily accessible and reliable list of breakdowns into functional components that I could have used instead. Of course, not all radicals are semantic components in the characters they appear in, and not all semantic components appear as radicals.

Anyway, I’m planning on rewriting this article from scratch and updating the list itself as well. I will then make the functional components part clearer!

Thank you very much for very useful resources.

My question is why to constrain ourselves with 100 radicals? When there are 214 of them.

I do understand that 100 is a bit less work. But why not to build full foundation rather then half?

Thank you very much.

This resource was created because at the time, there were no curated lists available (I really tried to find one). You either had ten or twenty or all radicals. The problem is that most of the rest of the radicals aren’t very useful, some of them are actually very rare. It’s also extremely easy to find lists of all radicals if that’s what you’re going for, even though I would say the pedagogical value of a list of all radicals sorted by stroke number is close to zero.

The real problem is of course that looking at radicals is of course completely the wrong approach. Like I say in the article, radicals in themselves are rather useless, they are only important insofar as they are often common semantic components in other characters. What would be awesome is a list of an arbitrary but fairly large number of components (semantic and phonetic), sorted by how productive they are in characters within a given set (say the 2,500 most common ones or something), but this in not a trivial task, especially since identifying components and their functions is not clear cut and can’t really be done reliably by a computer. The guys over at Outlier Linguistics probably have the data to do this, but the only product I’m aware of is their posters, but they don’t take you beyond the 100 mark either.

It was very helpful to me.

I was not able to understand any Chinese characters due to difficulty but I have just learnt word root of some Chinese like “forest” derived from “tree”.

I didn’t know that Chinese was a very interesting language. I wish to communicate with my roommate who can speak Chinese.

Glad you found it helpful! If you want a more in-depth discussion of how characters work, you can check out the series of articles and podcast episodes starting here: The building blocks of Chinese, part 1: Chinese characters and words in a nutshell

This is actually very useful. I am surprised that Chinese character were composed of several radicals into one. I have never thought that Chinese would be much easier after learning the radicals, I am hoping that I could write Chinese soon!! Thank you formaking this lesson, looking forward to see more of your contents!

Glad to hear you found it helpful! If you want to learn more about the building blocks of Chinese, you can always check out the series called The building blocks of Chinese, starting with this article.

This is a great post! I’m starting to learn Chinese and this will help me a lot.

This was very helpful, thank you!

Is it possible that you have written 子旁 occasionally where you meant 字旁?

Well spotted! There were indeed two instances of typing 子 instead of 字, which I have both fixed. Thank you!