Lists are nice. They make the world seem more orderly and manageable. Ticking something off a list feels good, and when you’ve worked your way through the whole list, you know that you’ve accomplished something. Progress!

No wonder that students love studying lists, ranging from official HSK lists, vocabulary lists from standard textbooks, or just random list of interesting or useful characters or words found online.

But a language is a complex system for communication, not just a list of vocabulary, so reducing it to that can be dangerous. Lists make the language seem orderly and manageable, but this is an illusion!

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Overcast, Spotify, YouTube and many other platforms!

In this article, I will discuss pros and cons with using lists for learning Chinese. As we will see, lists can be useful, but some lists are more useful than others, and they need to be used in the right way!

Why using vocabulary lists to learn Chinese is a good idea

First, let’s have a look at why you might want to use lists for learning new characters and words:

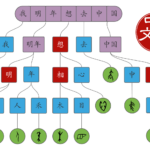

Lists are easy to find and access – There are more vocabulary lists online than you can possibly make use of in your life studying Chinese. Finding those words manually could take a very long time. Some lists are of very high quality, with audio recordings and images, which would be hard to replicate on your own. The same can be said for lists of the most common components, characters and words, which allow you to focus on the most useful content first.

Lists are easy to find and access – There are more vocabulary lists online than you can possibly make use of in your life studying Chinese. Finding those words manually could take a very long time. Some lists are of very high quality, with audio recordings and images, which would be hard to replicate on your own. The same can be said for lists of the most common components, characters and words, which allow you to focus on the most useful content first. Lists limit your options and help you focus – A list is ordered in a clear way and the task ahead of you is clear: just work your way through the list. You need to make few choices once you have selected the list. Analysis paralysis is a real issue, so not having to waste time considering what to do next is great. There are always more lists to continue with after you’ve finished the one you’re working on now, too.

Lists limit your options and help you focus – A list is ordered in a clear way and the task ahead of you is clear: just work your way through the list. You need to make few choices once you have selected the list. Analysis paralysis is a real issue, so not having to waste time considering what to do next is great. There are always more lists to continue with after you’ve finished the one you’re working on now, too. Lists make progress measurable – When you use lists, it’s easy to see how many characters and words you have learnt, which is highly motivating. Finishing a list and moving to the next is like ticking a huge, mental checkbox, telling your brain that you’re doing well. Compare this to some other, more vague learning activity where you don’t feel or see progress at all unless you’re a beginner. This is an especially serious problem once you’ve reached the intermediate plateau.

Lists make progress measurable – When you use lists, it’s easy to see how many characters and words you have learnt, which is highly motivating. Finishing a list and moving to the next is like ticking a huge, mental checkbox, telling your brain that you’re doing well. Compare this to some other, more vague learning activity where you don’t feel or see progress at all unless you’re a beginner. This is an especially serious problem once you’ve reached the intermediate plateau. Lists are convenient to review – Most flashcards apps, such as Anki, Skritter or Pleco, have a feature where you can study lists created by others. With a few clicks, you can find all sorts of vocabulary lists and add hundreds or even thousands of words. These apps then let you review these words over time, making sure that they stick, which requires much less effort than keeping track of interesting words you encounter here and there.

Lists are convenient to review – Most flashcards apps, such as Anki, Skritter or Pleco, have a feature where you can study lists created by others. With a few clicks, you can find all sorts of vocabulary lists and add hundreds or even thousands of words. These apps then let you review these words over time, making sure that they stick, which requires much less effort than keeping track of interesting words you encounter here and there. Lists split the language into manageable chunks – Learning words, characters or even components allows you to tackle the language one small unit a time. Reading text or listening to flowing speech is hard; learning the building blocks makes it easier. As mentioned above for measurable progress, smaller chunks also give you a sense of achievement.

Lists split the language into manageable chunks – Learning words, characters or even components allows you to tackle the language one small unit a time. Reading text or listening to flowing speech is hard; learning the building blocks makes it easier. As mentioned above for measurable progress, smaller chunks also give you a sense of achievement.- Lists collect related words and make the easy to access – If you want to brush up on your computer vocabulary in Chinese or find words related to sports, you can find a list of words that cover these topics. This is significantly faster than reading and listening so much that you can collect these words yourself.

Each of these are valid reasons for using lists in some way, and I think that combined, they account for the bulk of the explanation as to why students of Chinese (and other languages, of course) tend to rely on lists a lot.

But that doesn’t mean that you should use them all the time or that there aren’t problems associated with using lists. There’s a fair amount of research into vocabulary acquisition related to lists, and even if it doesn’t unanimously discard lists as a source for vocabulary, lists aren’t as good as you might think. Let’s turn the above pros around and see how they can actually also be cons.

Why using vocabulary lists isn’t such a good idea after all

As I said in the introduction, a language is a complex system for communication. It would be naïve to think that you could master Chinese simply by studying lists of characters and words, but even if few students think that’s the case, many act as if it were at least partly true. If your Chines diet consists mostly of HSK vocabulary lists and test preparation, then you’re missing both more fun and more useful methods!

Here’s the other side to the above advantages:

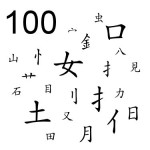

Lists are easy to find and easy to access… but how do you know that you’ve found the right list? The fact that you can find and use lists easily by searching online doesn’t necessarily mean that the lists you find are suitable for you or that they are of high quality. For example, a frequency list based on newspaper text is not suitable for boosting vocabulary for spoken language. Or a list compiled by another beginner based on a textbook with bad translations is not the best source for new vocabulary either. Learning all radicals is a waste of time, but learning the most common 100 is a great idea. It all depends.

Lists are easy to find and easy to access… but how do you know that you’ve found the right list? The fact that you can find and use lists easily by searching online doesn’t necessarily mean that the lists you find are suitable for you or that they are of high quality. For example, a frequency list based on newspaper text is not suitable for boosting vocabulary for spoken language. Or a list compiled by another beginner based on a textbook with bad translations is not the best source for new vocabulary either. Learning all radicals is a waste of time, but learning the most common 100 is a great idea. It all depends. Lists limits your options and help you focus… but aren’t you just ignoring the problem? Not having too many choices is good as a beginner; you need guidance. However, since learning Chinese is a complex task with many things to do that can be done in many different ways, hiding within the confines of a vocabulary list won’t really help; you’re just ignoring the complexity of the problem. If you really trust the person making the choices for you and they know of your situation, motivation and goals, you might be fine, but probably not. For example, even the official HSK lists contain lots of useless words, omissions and other oddities. The same goes for the TOCFL lists.

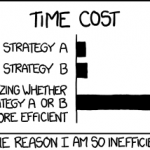

Lists limits your options and help you focus… but aren’t you just ignoring the problem? Not having too many choices is good as a beginner; you need guidance. However, since learning Chinese is a complex task with many things to do that can be done in many different ways, hiding within the confines of a vocabulary list won’t really help; you’re just ignoring the complexity of the problem. If you really trust the person making the choices for you and they know of your situation, motivation and goals, you might be fine, but probably not. For example, even the official HSK lists contain lots of useless words, omissions and other oddities. The same goes for the TOCFL lists. Lists make progress measurable… but are you measuring the right thing? – I believe that measurable progress is great, but as soon as you start measuring, you need to be careful that you’re measuring the right thing. You are, after all, trying to learn Chinese, not only Chinese characters and words. I’ve written two articles about this problem already: The importance of counting what counts when learning Chinese and Measurable progress is a double-edged sword. Yes, you’re making a lot of progress if you measure how many words you can handle in your flashcard app, but does that mean that you can use them? Even if you could, is that equal to proficiency? Not really. Focusing only on lists would be a bit like going to the gym to get stronger in roder to become better at basketball, but then never really leave the gym.

Lists make progress measurable… but are you measuring the right thing? – I believe that measurable progress is great, but as soon as you start measuring, you need to be careful that you’re measuring the right thing. You are, after all, trying to learn Chinese, not only Chinese characters and words. I’ve written two articles about this problem already: The importance of counting what counts when learning Chinese and Measurable progress is a double-edged sword. Yes, you’re making a lot of progress if you measure how many words you can handle in your flashcard app, but does that mean that you can use them? Even if you could, is that equal to proficiency? Not really. Focusing only on lists would be a bit like going to the gym to get stronger in roder to become better at basketball, but then never really leave the gym. Lists are convenient to review … but are you learning the words properly? Many students, including myself, go through some period where they binge on new vocabulary, recklessly importing various lists into the flashcard program of their choice. However, while it is convenient, I’ve found that I seldom learn these words as thoroughly as those that I add or edit manually myself. Learning is not always convenient. Deep processing requires effort and focus. Your flashcards will only cover a small part of what it means to know a word.

Lists are convenient to review … but are you learning the words properly? Many students, including myself, go through some period where they binge on new vocabulary, recklessly importing various lists into the flashcard program of their choice. However, while it is convenient, I’ve found that I seldom learn these words as thoroughly as those that I add or edit manually myself. Learning is not always convenient. Deep processing requires effort and focus. Your flashcards will only cover a small part of what it means to know a word. Lists split the language into manageable chunks … but words don’t exist in a vacuum! This is in fact one of the major disadvantages with learning vocabulary in isolation, such as from a list. As I said above, a language is more than just vocabulary. You can’t just pile words randomly on top of each other and hope that they make sense. Knowing a word is about so much more than the definition, such as how it’s used (which can be complex), register, connotations and so on. You simply won’t get this from a list, no matter how good it is. You will only get that through extensive reading and listening.

Lists split the language into manageable chunks … but words don’t exist in a vacuum! This is in fact one of the major disadvantages with learning vocabulary in isolation, such as from a list. As I said above, a language is more than just vocabulary. You can’t just pile words randomly on top of each other and hope that they make sense. Knowing a word is about so much more than the definition, such as how it’s used (which can be complex), register, connotations and so on. You simply won’t get this from a list, no matter how good it is. You will only get that through extensive reading and listening.- Lists collect related words… but this makes them easier to confuse! There’s plenty of research that shows that learning words that have related meanings, such as twenty types of fruit or all the colours in a language, makes it significantly harder to remember the words. This is because of interference between the words. Generally speaking, if you learn two similar things at the same time, it will be harder to untangle them from each other later. However, comparing similar words can still be useful if you already know the words (see e.g. Nation, 2000).

As we can see, learning directly from a vocabulary list has certain drawbacks. You can get around some of them by using carefully curated content, having a competent teacher and being an independent learner who knows about the potential pitfalls. My hope is that this article has helped you towards becoming more aware of the problem.

Vocabulary lists can still be useful

I don’t mean to say that you should never learn vocabulary from a list. In fact, in most apps that rely heavily on word lists, such as Skritter, you aren’t meant to use the apps in isolation. If you’re studying a textbook anyway, having all the words already added to a flashcard app is awesome and saves so much time! The same goes for a graded reader you are going through. Naturally, you might want to add or remove words from the official list, but modifying an existing list is still better than creating everything on your own from scratch.

When I say that you shouldn’t learn characters and words from a list, I mean that if you’re seeing them for the first time in that list, you’re doing something wrong. There are cases where lists are a legitimate source of new vocabulary, though, but these are limited. A good example would be when you want to plug gaps in your vocabulary on a level significantly lower than your current one, or as preparation for listening or reading practice that would otherwise be too difficult.

If I shouldn’t learn vocabulary from a list, how do I know what to learn?

As we have seen, list shouldn’t be the main source of new vocabulary. In general, if you feel that you don’t have enough words to learn, you aren’t listening and reading enough. If you have enough words to learn, but don’t know which to learn first, you can normally rely on either their importance for you personally (if you think the word is important, it probably is) or their frequency in the kind of Chinese you engage with (only learn things that appear often). I’ve written more about which words you should learn and where to find them here:

There’s much more to say about different kinds of lists, especially frequency lists, which I have talked about here: Vocabulary lists that help you learn Chinese and how to use them

Vocabulary lists that help you learn Chinese and how to use them

References and further reading

Folse, K. S. (2004). Myths about teaching and learning second language vocabulary: What recent research says. TESL reporter, 37, 13-13.

Gholami, J., & Khezrlou, S. (2014). Semantic and Thematic List Learning of Second Language Vocabulary. CATESOL Journal, 25(1), 151-162.

Nation, P. (2000). Learning vocabulary in lexical sets: Dangers and guidelines.

Papathanasiou, E. (2009). An investigation of two ways of presenting vocabulary. ELT journal, 63(4), 313-322.

Schmitt, N. (2008). Instructed second language vocabulary learning. Language teaching research, 12(3), 329-363.

Webb, S., & Nation, P. (2017). How vocabulary is learned. Oxford University Press.

Tips and tricks for how to learn Chinese directly in your inbox

I've been learning and teaching Chinese for more than a decade. My goal is to help you find a way of learning that works for you. Sign up to my newsletter for a 7-day crash course in how to learn, as well as weekly ideas for how to improve your learning!