I’ve talked, read and written about Mandarin Chinese pronunciation and Pinyin a lot, both in casual and academic settings, both in English and Chinese.

I’ve talked, read and written about Mandarin Chinese pronunciation and Pinyin a lot, both in casual and academic settings, both in English and Chinese.

Something that I have noticed is that people often fail to distinguish between pronunciation and Pinyin. This might look like an innocent and rather small mistake, but as I’m going to show in this article, it can be a real problem.

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcast, Overcast, Spotify and many other platforms!

Chinese pronunciation and Pinyin are not the same thing

Let’s start by sorting out what’s what before we go on to discuss what the consequences for getting this wrong can be:

- Pronunciation refers to how we say words in a language, specifically which sounds are used and what characterises them. In short, pronunciation is about sounds and how we produce them. From a practical point of view, good pronunciation is about using sounds that make it easy for speakers of that language to understand what we’re saying. From a formal point of view, good pronunciation is about following an officially sanctioned standard. For more about this, please check out this article about what correct pronunciation even means: Standard pronunciation in Chinese and why you want it.

- Pinyin, short for Hànyǔ Pīnyīn (汉语拼音), is the most commonly used romanisation system for Mandarin Chinese, meaning that it is a way of writing the language using the Latin alphabet. While it’s clearly related to sound, Like all transcription systems like this, it is an artificial and designed system for writing down spoken words. There are many others, the most common one being Zhuyin. What I’m talking about in this article is relevant for both, but I will use Pinyin as an example. For more about other systems, please head over to this article: Learning to pronounce Mandarin with Pinyin, Zhuyin and IPA: Part 1

So, pronunciation is the real thing; it’s about the sounds of the spoken language. Pinyin (or any other transcription system) is just a way of referring to the sounds of the spoken language in written form.

While it could be argued that spoken language is also man-made, it has evolved much more organically than any writing system. Written language is more artificial and can be regarded as an invention.

This is particularly true for systems like Pinyin, which really is a designed construct, even if it is of course based on the evolution of earlier, similar systems.

Two different things might sometimes appear to be the same

To someone who teaches and researches pronunciation, it’s strange to treat pronunciation and Pinyin as one and the same, but in my experience, it’s fairly common among both students and teachers of Chinese with less experience and interest in these topics.

This is not too hard to understand why, though, because from a practical point of view, they can be superficially identical.

Let’s look at two examples:

- If you say a word like 去 (qù), “to go”, but pronounce it with a normal “u” sound [u] instead of “ü” as it’s supposed to be (that’s [y] in IPA), and someone points this out to you, it could be that you don’t know how to pronounce [y], but it could also be that you haven’t learnt Pinyin properly. This is one of many traps and pitfalls students often fall into when learning Pinyin. The problem is that it’s impossible to tell if you have a problem with Pinyin or with pronunciation just by looking at that one mistake! It would be easy to tell which with some further probing, but without that, they are identical. For example, if you can pronounce the “ü” in 女 (nǚ), “woman”, but not in 雨 (yǔ), “rain”, it’s likely that you simply don’t know that the sound spelt “yu” is actually pronounced [y]. If you get both of them wrong, your problem is not limited to Pinyin.

- In most beginner Chinese courses, pronunciation and Pinyin are treated as the same thing. Pinyin and pronunciation are both covered together, in parallel, both in textbooks and curricula. Typically, this involves an intense period at the very beginning where you learn about the sounds (pronunciation) and how they are written down (Pinyin). Sadly, it’s then often assumed that students know pronunciation after this point, and little effort is put into teaching pronunciation beyond the first few weeks of class.

The problem here is of course that learning Chinese pronunciation and learning Pinyin are completely different processes. Problems in these areas require different solutions, so confusing one with the other will lead to slower progress.

The real challenge is pronunciation…

Learning pronunciation is the real challenge, of course. It requires you to learn a bunch of new sounds, redefine some sounds you already know from other languages, and then make all this work together in real time.

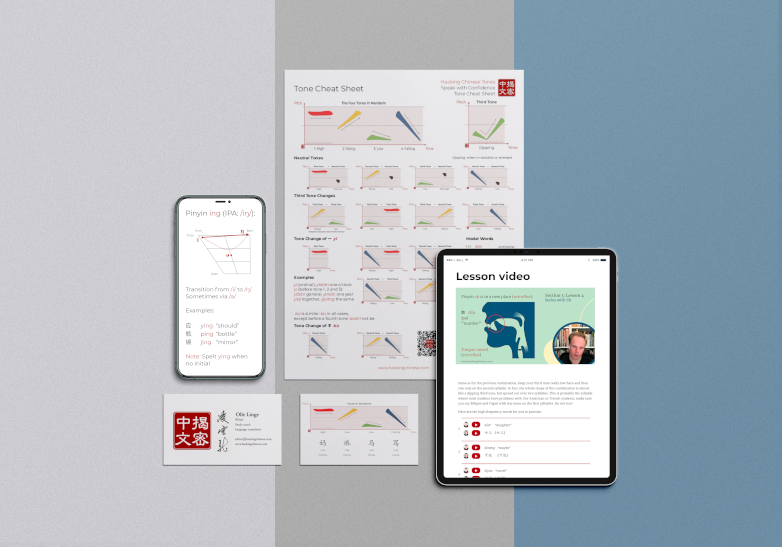

For the average student, this takes a long time, often years. The reason it takes a lot of time is because you need to hear the language a lot, and the way most people study, they don’t do this nearly enough. If you focus a lot on pronunciation, listen and mimic as much as you can, it can be done much faster. This can be done on your own, but if you prefer my guidance, you should check out my pronunciation course, which opens for registration again on May 10th:

…but learning Pinyin is easy

Learning Pinyin, on the other hand, is very easy. It’s just a matter of mapping some 20 initials, some 40 finals and four tone marks to the sounds of the language. If you know other languages using the Latin alphabet, you have many mappings for free. Naturally, there are some traps and pitfalls to be aware of, but these can be easily avoided!

Provided that you know how to pronounce Mandarin, Pinyin can be mastered in a matter of hours. I know this because I’ve learnt other transcription systems such as Zhuyin after learning the sounds and it really only takes a few hours.

The fact that many people are baffled by this and think that learning something like this is hard further proves the point that they are confusing pronunciation itself with the way we write. Learning a new phonetic writing system is not hard, but learning the sounds is!

Mastering Pinyin is not the same as mastering pronunciation

It should be clear by now why this is a problem. If you think that you know pronunciation just because you know how Pinyin works, you might be in for a surprise when you get a true evaluation of your pronunciation.

This is a particularly serious problem if teachers believe this, because while it’s certainly possible to go through everything a student needs to know about Pinyin in a week (I have done this many times with beginner students at university), it is not possible for normal people to learn to pronounce Mandarin clearly in a week. This, if you teach Pinyin and think that you have also taught pronunciation, you’re in dangerous territory!

Learn pronunciation before Pinyin, if you can

Ideally, pronunciation should be taught before Pinyin. The reason is that orthography (i.e. the way we write) does have an influence both on what we hear and what we say. This means that if you see a certain letter together with a certain sound, it might lead your perception astray.

For example, students tend to cheat and rely on their native language when using Pinyin. If you see that 是 is spelt shì in Pinyin, you’re probably more likely to pronounce it as “she” in English than if you only heard the sound (which is actually not that similar to an “i” or “e” sound). If you learnt to hear the sound first and only then learnt how to write it, I’m sure we would have less people saying “woe she may go run” (我是美国人/我是美國人). It wouldn’t make pronunciation easy, but it would remove some minor obstacles at least.

However, teaching pronunciation like this is impractical and time-consuming. Adult students typically feel frustrated if you give them nothing in writing (believe me, I’ve tried) and it’s very hard to take any notes, review properly, and so on, without having written references. Yes, it is possible, but the reason it’s still rare to see it is that it requires a lot of effort.

What ends up happening instead is the opposite: most students learn Pinyin before they learn pronunciation. What do I mean by that? I mean that they learn spelling rules and how Pinyin works before they can even hear the sounds of the language. If you struggle with hearing the sounds, check out this article: Learning to hear the sounds and tones in Mandarin. This is especially true if Pinyin is squeezed into a very short amount of time at the beginning of the course.

This is one of the main reasons I created my current pronunciation course here on Hacking Chinese: Most students don’t actually get the support they want and need from their teachers and courses, not to mention people who study on their own. It’s also notoriously difficult to get an honest assessment on your pronunciation elsewhere! If a professional and honest assessment is what you’re after, that is available as an add-on to the pronunciation course I mentioned above.

What is actually included in “pronunciation”?

Finally, now that we know that Pinyin and pronunciation are two separate things that need different types of studying, let’s look more closely at the word “pronunciation” and how it’s used, both in Chinese and English, because I think this contributes to the confusion.

I have spoken with dozens of Chinese teachers and taken many grad school courses in phonetics and phonology, all in Chinese. I have also talked about pronunciation with many native speakers, also in Chinese. One interesting observation is that in Chinese, fāyīn (发音/發音) sometimes only refers to the initials and finals, not the tones, which would then be shēngdiào (声调/聲調). Thus, someone might say “你的发音很好, 但是你的声调需要多练习”, which could be translated as “your pronunciation is good, but you need to practise your tones more”.

From a linguistics perspective, this doesn’t make much sense, as tones are most certainly included in how we pronounce words (that’s actually part of the definition of what lexical tones are).

Still, this is how many people use these words, and it’s good to be aware of the fact that there can be a distinction in Chinese. There doesn’t have to be one, though, so fāyīn (发音/發音) can certainly include tones as well.

You can sometimes see this reflected in English usage as well, even though I’m not sure if there’s a causal relationship. This would mean that the initials and finals in Pinyin are somehow treated differently than the tones.

For example, you might have a teacher who uses the words like I described them in Chinese above, so they might believe that your pronunciation is great, but that your tones suck (although they won’t tell you that). There are also students who ask questions like “Can I write without tones on the exam?”, which either tells me they’ve been sleeping up to this point, or that they are lazy and try to find shortcuts. The answer is of course, no , tones in Mandarin are not optional!

Conclusion

So, in case you were confused about the difference between pronunciation and Pinyin, I hope that I have cleared that up for you! I also hope that I’ve made clear why making a clear distinction between Pinyin and pronunciation in your head is actually important and will help you to improve your Mandarin.

If you want more insightful advice, along with a complete video guide to Mandarin pronunciation (and Pinyin, of course), I’m opening my pronunciation course for registration on May 10th, so be sure to check it out!

If you’re not interested in the course, I have written more than fifty free articles about pronunciation. Here ore some of my favourites:

How learning some basic theory can improve your Mandarin pronunciation

Learning to pronounce Mandarin with Pinyin, Zhuyin and IPA: Part 1

How to find out how good your Chinese pronunciation really is

A smart method to discover problems with Mandarin sounds and tones

A guide to Pinyin traps and pitfalls: Learning Mandarin pronunciation

About fossilisation and improving your Chinese pronunciation

https://www.hackingchinese.com/24-great-resources-for-improving-your-mandarin-pronunciation/

Tips and tricks for how to learn Chinese directly in your inbox

I've been learning and teaching Chinese for more than a decade. My goal is to help you find a way of learning that works for you. Sign up to my newsletter for a 7-day crash course in how to learn, as well as weekly ideas for how to improve your learning!