As Infants, we don’t yet rely on categories to make sense of the world; everything is a glorious mess. When we engage with our first language, we establish sound categories that enable us to understand, but we also lose the ability to deal with sounds that aren’t important.

As Infants, we don’t yet rely on categories to make sense of the world; everything is a glorious mess. When we engage with our first language, we establish sound categories that enable us to understand, but we also lose the ability to deal with sounds that aren’t important.

When we learn a second language as adults, we need to regain that ability.

But how?

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode (#198):

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Overcast, Spotify, YouTube and many other platforms!

Overview

To make this article easier to navigate, here’s a table of contents:

- We gradually learn to not hear sounds we don’t need

- Learning to perceive sounds in our first language

- Learning to hear new sounds and tones as an adult is not easy

- You learn to distinguish new sounds through input

- Underlying patterns of speech sounds are hard to untangle

- Input and engagement are often enough to learn new sounds and tones

- Method 1: High-variability training

- My graduate school research project about tone perception

- Method 2: Perceptual training through exaggeration

- Exaggerating tones to hear them better

- Conclusion: Learning to hear new sounds and tones

- References and further reading

We gradually learn to not hear sounds we don’t need

Being able to perceive the world without filters and categories might seem like a superpower at first, but it isn’t. Perceiving everything is the same as perceiving nothing.

The underlying sound system of a language is less complex than one might think. A typical language might have slightly less than ten categories for vowels and slightly more than twenty for consonants. Tonal languages add a handful of tones, but that’s it.

These sound categories are called phonemes. A phoneme is simply a sound that can be used to distinguish the meaning between different words in the language.

- In English, “seal” and “zeal” are two different words, one with /s/ at the start and one with /z/. In Mandarin, though, sān (三) means “three”, but if you pronounce it with a /z/, it’s just a weird way of saying the word; it doesn’t mean something else.

- In Mandarin, mǎi (买) and mài (卖) mean “buy” and “sell” respectively, but in English, “my” pronounced with different tones still means that something belongs to you, even though you can indicate that it’s a question by raising the tone, for example.

For more about the basics of tones, please check The Hacking Chinese guide to Mandarin tones:

Learning to perceive sounds in our first language is almost always successful

Mastering the sound system of our first language is about being able to accurately sort sounds into the categories that are relevant to that language. Thus, Chinese children notice that tones are important in their language and so they maintain the ability to distinguish them. They don’t need to distinguish between /s/ and /z/, so they forget to do that. Engilh-speaking children don’t need tones, so don’t develop the ability to sort words based on pitch contours.

This process is automatic and almost always successful, but only for languages you engage with the sounds as an infant. While the idea of a critical period after which you can’t learn to hear or say sounds in a new language is not true, it is certainly true that this becomes harder as you grow older.

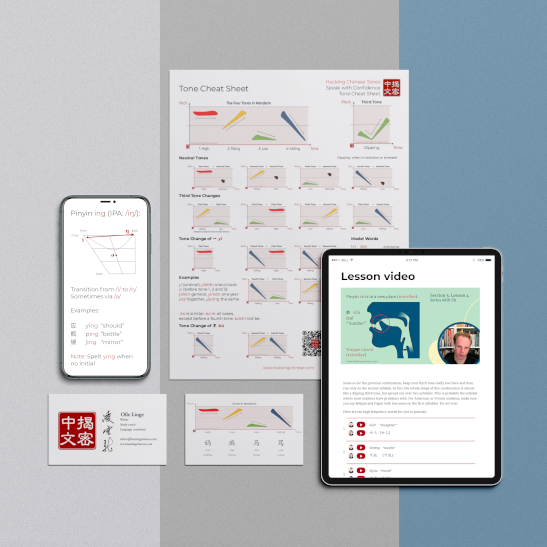

For more structured guidance about learning Mandarin pronunciation as an adult, check my course Hacking Chinese Pronunciation: Speaking with Confidence.

In this article, we’re going to look at how to learn to hear the sounds of a new language as an adult. Since this is Hacking Chinese, we’re going to focus on Mandarin here, so tones are included. After saying some general things about learning new sounds, we will look closer at two methods that have been proven to work.

Learning to hear new sounds and tones as an adult is not easy

Creating or modifying sound categories as an adult is not easy, but it can be done, which is easy to show because otherwise, no English native speakers would be able to hear or say the tones in Mandarin, and no native speakers of Chinese would be able to hear the difference between “seal” and “zeal”.

While this type of second-language perception might not be identical to first-language perception, it can certainly be functionally equivalent and enable smooth communication in the language.

It’s not clear exactly what makes some sounds harder than others (for an overview of the research in this area, see Escudero, 2009). In some cases, completely new sounds can be easier because they are so obviously different from what you are used to. In other cases, sounds that are used in your native language but aren’t used to distinguish words might be harder.

The most researched example of the latter is the challenge of learning to distinguish /r/ and /l/ by adult Japanese learners of English. These are two different phonemes in English, but not in Japanese. However, both sounds do occur in Japanese, but it’s just something that happens to a sound in a specific context.

You learn to distinguish new sounds through input

To create new categories for sounds and tones, your brain needs input. As we saw in part two of my series Beyond tīng bu dǒng, being able to synthesise meaning out of a stream of spoken sounds is much more complex than people realise.

The problem is that while it’s easy to say that the difference between mǎi and mài is the tone simply describing the difference that does not enable you to suddenly hear it. This is because there are so many other things going on at once. For example, different speakers have different voices and say words differently in different contexts.

Beyond tīng bu dǒng, part 2: From sound to meaning in Mandarin

Underlying patterns of speech sounds are hard to untangle

Yet, underlying all this, there is a pattern to each tone that allows native speakers to process each word correctly. As an adult learner, your brain needs to remove all the unimportant cues and figure out what matters. Deep down, what is the difference between a third and a fourth tone?

The only way to do this is through input. You need to listen as much as possible and you need to know when you’re right and when you’re wrong. As we shall see, you also need varied input.

Input and engagement are often enough to learn new sounds and tones

In my experience as a teacher, most students learn to hear most sounds and tones without focusing on them explicitly. Some struggle with certain aspects of it, and others have an easier time, but on the whole, simply engaging with the language in a meaningful context and listening a lot will do the trick.

Most of the time. But what about when this doesn’t work? What if you just can’t hear the difference between two sounds or tones? How can you train yourself to learn to hear them?

Fortunately, two methods have been proven to work:

- High-variability training

- Perceptual training through exaggeration

Method 1: High-variability training

One of the most successful methods relies on systematic feedback using sounds produced by several native speakers. This gives your brain enough input to figure out what is particular to a certain speaker and what is a key element of the tone. By systematically receiving feedback on your perception of one speaker, you build competence locally, which can then be expanded with subsequent speakers.

Compare this with the normal foreign-language classroom situation where one or at most two native speakers are heard, rarely in a systematic fashion. This will allow you to hear the sounds and tones your teacher pronounces, but might not help establish perceptual categories that are robust enough to work in the real world.

But if you can correctly identify the sound you hear, and then hear this sound from several different speakers, your brain will have the information necessary to figure out which parts are crucial for understanding and which can be ignored. For instance, absolute pitch height is not a crucial part of identifying tones; it’s how the tones change that matters. All fourth tones are falling, but they start and end at different heights depending on the length and thickness of the speaker’s vocal cords. Children usually have higher-pitched voices than females, who in turn usually have higher-pitched voices than males, yet a high tone is still a high tone, and a low tone is still a low tone, relatively speaking.

My graduate school research project about tone perception

In grad school, I conducted some research in this area. With the help of Kevin Bulloughey at WordSwing, I built a tone-training course. In essence, it puts you through systematic exposure to tones spoken by different speakers, gradually helping you to form the correct categories for the basic tones in Mandarin. If you’re interested, the course is still available; please check this article.

This course will be too easy for most intermediate and advanced students (there is a pretest that will tell you if you’re in the target group or not). However, the underlying principle is still the same, regardless of language or the level you have attained in it: You need lots of input from many different speakers to feed your brain enough data to be able to correctly identify sounds and tones.

See the references at the end of this article for recommended reading, but as mentioned, I might return to this topic later considering that I’ve spent hundreds of hours researching it.

Method 2: Perceptual training through exaggeration

The other method that seems to work relies on something which should be familiar to most readers, although maybe not by name: child-directed speech (CDS). That’s the exaggerated, slightly high-pitched language adults instinctively use when they speak to children. This also works for adults, or at least the exaggeration does.

The idea is that if the learner needs to identify a boundary between two distinct sounds, it makes sense to first learn to identify two exaggerated versions that will be impossible to miss. For example, if the teacher pronounces Pinyin “p” with so much aspiration that you get knocked off your feet, you’re unlikely to miss the point. Then, the teacher gradually decreases the exaggeration until pronunciation becomes natural and normal.

Exaggerating tones to hear them better

Let’s look at an example with tones, namely the difference between the second tone and the dipping third thone, They both have a dip, but the the main difference is that the third tone rises much later. By starting with second tones that rise immediately and aggressively, and third tones that rise very late, the teacher can help you identify the crucial component (the turning point). Then the teacher gradually reduces the exaggeration and approaches the actual boundary between the two.

This method works particularly well if you have already identified two similar sounds that you find difficult to distinguish, but it’s harder to use as a general approach for learning new sounds (you need to contrast two sounds and it’s not always obvious which sounds you should combine). Another issue is that the teacher needs to know what they’re doing in some cases because otherwise, exaggeration might make them pronounce the sounds in a completely different way.

Still, the principle of exaggeration works in general and can be used with teachers or language exchange partners, and many people will do this naturally when someone has a problem understanding what they’re saying. It’s hard to do on your own, though.

Conclusion: Learning to hear new sounds and tones

As an adult learner of a tonal language like Mandarin, you need systematic input from several different speakers. That will allow you to gradually identify what part of the input is essential for identifying the right word. Combined with this, try having someone exaggerate distinctions you find extra hard and see if that helps!

References and further reading

Escudero, P. (2009). The linguistic perception of similar L2 sounds. In: P. Boersma & S. Hamann (red.), Phonology in perception, 15 (s. 151–190). De Gruyter Mouton.

Wang, X. (2008). Training for learning Mandarin tones. Handbook of research on computer-enhanced language acquisition and learning, 259-274.

Wang, Y., Spence, M. M., Jongman, A., & Sereno, J. A. (1999). Training American listeners to perceive Mandarin tones. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 106(6), 3649-3658.

Zhang, J., Wang, X., Sun, Y., Nishida, M., Zou, T., & Yamamoto, S. (2013). Improve Japanese C2L learners’ capability to distinguish Chinese tone 2 and tone 3 through perceptual training. In Oriental COCOSDA held jointly with 2013 Conference on Asian Spoken Language Research and Evaluation (O-COCOSDA/CASLRE), 2013 International Conference (pp. 1-6).

Editor’s note: This article, originally published in 2015, was rewritten from scratch and massively updated in May 2024.

Tips and tricks for how to learn Chinese directly in your inbox

I've been learning and teaching Chinese for more than a decade. My goal is to help you find a way of learning that works for you. Sign up to my newsletter for a 7-day crash course in how to learn, as well as weekly ideas for how to improve your learning!

3 comments

This looks pretty interesting. I’m sort of in a middle way to understand tones, but quite far from using them correctly all the time without having to recall each one, and certainly would benefit from some more basics, I’m going to give it a try! Thanks for the chance!

Thanks a lot for such useful guide!

Well, if I try to learn I’ll be a beginner, at least beyond hearing my preschool best friend’s parents speaking when I was like 2-5, but I don’t recall ever trying to learn then or at other times I was passively exposed as a child. I can be fresh data for the project. I am curious myself because I have a musical background and a good ear for it, but I also have CAPD, which is more about word differentiation, as well as autism and learning disabilities. It will be fascinating to see whether this makes learning a tonal language easier or harder; I always found reading, writing, and even speaking easier than hearing, regardless of language. But perhaps tonal phrases will prove easier than I anticipate and I’ll be pleasantly surprised that isn’t the trickiest part.

Curiosity is a good motivator. Time to invest is the antagonistic factor.