In this article, I will continue the story of how I learnt Chinese. In previous parts, I have already talked about why I started learning and what it was like to study Mandarin in Sweden. After the first year, I moved to Taiwan to continue learning.

In this article, I will continue the story of how I learnt Chinese. In previous parts, I have already talked about why I started learning and what it was like to study Mandarin in Sweden. After the first year, I moved to Taiwan to continue learning.

This post is part of a series; here are the other parts:

- Where it all started

- Learning Mandarin in Sweden

- My first year in Taiwan (this article)

- My second year in Taiwan

- Returning to Sweden

- Graduate program in Taiwan

- Teaching, writing, learning

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Overcast, Spotify, YouTube and many other platforms!

Going to Taiwan

This meant learning in an immersion environment combined with fairly traditional language lessons. This brought me into contact with a whole new range of issues with language teaching as done in the Chinese-speaking world. As a result of this, I started experimenting more on my own and learnt a lot about how to compensate for the weaknesses in courses and curricula.

The decision to continue to study Chinese in Taiwan was mostly a coincidence. My teacher in Sweden forwarded a note about a scholarship (the Huayu Enrichment Scholarship) and I applied for it without really expecting either to get it or to continue studying Chinese. When I actually received the scholarship, I sort of had to go. You don’t turn down the offer of studying a language for one year with most costs covered.

Arriving in Taiwan – 中華大學

Arriving in Taiwan – 中華大學

I spent the first semester at 中華大學 outside 新竹. All Taiwanese who hear that ask the same question: Why? It’s a young university with a technical profile and completely unknown for their language centre. The truth is that I went there because they were one of the few institutions who really cared about me.

You see, when I applied for the scholarship, I had missed the fact that I was also supposed to have applied to a university, which I hadn’t. I had to do that really fast. I sent e-mails to all institutions on the official list. Most didn’t even bother to reply. Out of the few that did, 中華大學 was the only one that seemed to care about each individual student. This seemed important, so I went there.

Arriving in Taiwan was overwhelming, but mostly in a positive way. All things practical went very smoothly, and I received great help from the university. The biggest chock was language, which I touched upon in the previous article. To summarise, I could say a few things, but found it impossible to understand what people said. I understood perhaps 50% of what was said in class. My classmates had studied for about as long as I had, but mostly in Taiwan, which makes a huge difference.

Even though I think spending a few months at 中華大學 wasn’t so bad, it became apparent towards the end of the first semester that it wouldn’t work in the long run. I was the only full-time language student in my class, and spent perhaps five times as many hours as they did per week learning Chinese. I was far behind when I started, but felt that things had already become too easy when Christmas neared.

Another problem was that our classes were held in the evening, which meant it was very difficult to find native speakers to socialise with; I had time during the day when everybody worked or went to class, I was busy when they had time off. I needed a bigger language centre with more options and other people who took learning as seriously as I did.

Moving on – 文藻外語學院

Moving on – 文藻外語學院

For various reasons, my choice fell on 文藻外語學院 in 高雄, Taiwan’s second-largest city located in the south. 文藻 is a language college with a bigger language centre and filled with native students interested in languages.

While this provides a better learning environment in general, larger institutions also come with some problems. Each student matters less, and it’s less likely that they will make exceptions for you or accommodate to your needs in general. At 文藻, it still worked, but I had to push for it a lot harder.

For example, after taking the placement test, I was placed in a class which focused on the third book in the 遠東生活華語 (Far East Everyday Chinese) series. This was probably accurate in the sense that it was roughly on par with the course I had taken the previous semester. However, the whole point of transferring to 文藻 was that the pace was too low! I realised quickly that I had to do something to avoid the same problem occurring again.

I discussed the issue with the responsible teachers at the school and basically asked them what the most difficult class they had was, then asked to join it. They flatly refused (and rightly so). I then asked what the second most difficult class was and asked if I could join that one instead. They said no. I pleaded a bit and asked at least be allowed to try it. They said okay, but that I only would be allowed to stay if the teacher agreed.

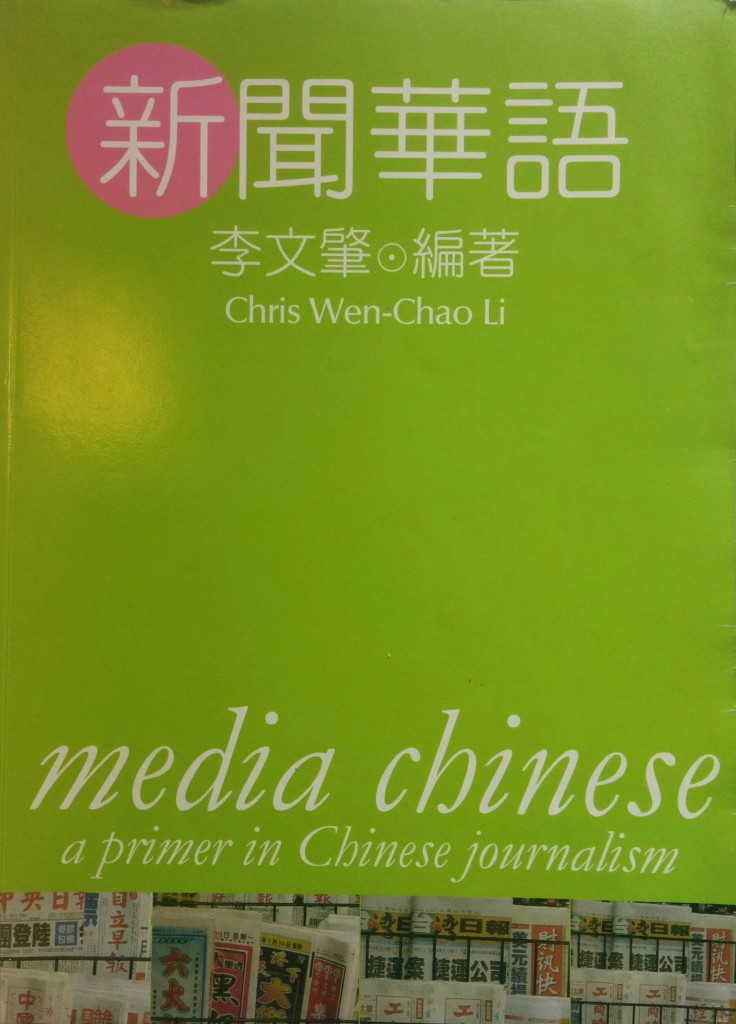

The book we used was 新聞華語 (Media Chinese), which turned out to be really hard. I spent hours preparing for each class, and articles sometimes had more than a hundred new words.

The book we used was 新聞華語 (Media Chinese), which turned out to be really hard. I spent hours preparing for each class, and articles sometimes had more than a hundred new words.

All my classmates were more or less fluent in Mandarin, whereas I still had to struggle both to understand and to express my own thoughts. However, I had both the time and the motivation necessary and stayed afloat throughout the semester.

I was allowed to stay, and although I didn’t catch up with my classmates who were simply too far ahead, I learnt an incredible amount of Chinese. I was miles ahead of the people who stayed in the class where I was originally placed. I’ve written more about this in Is taking a Chinese course that’s too hard good for your learning?

Social life and language learning

Learning in a classroom is not enough, even if the classroom is located in a Chinese-speaking environment. Most language schools are fairly traditional and stay close to the textbook, focusing a lot on reading and vocabulary. Even though I spoke a lot in class too (small class size is a blessing), that was far from enough. I limited my use of English to about once per week when I played role-playing games with a group of other foreigners. The rest of the time I spent with native friends, language exchange partners and foreign classmates whose Chinese was a lot better than mine. I also practised some sports, such as diving, which meant I got to know native speakers who were far from campus, both literally and metaphorically speaking.

I think this approach was just right for me; I benefited a lot from the difficult class I was in, but the danger was of course that I had skipped a lot of more elementary language that I now had to cover on my own. This is not difficult if you have the time to spend, but can result in an advanced but narrow competence if you’re not careful.

Most of the time with native speakers was spent on simply talking about things, mostly unrelated to my textbooks. An interest in languages was also a great common denominator between me and the Taiwanese students, which meant it was fairly easy to make friends.

Lessons learnt from my first year in Taiwan

So, what did I learn during this first year that other students can benefit from? Here’s a selection of important insights I think are worth sharing:

- Don’t invent the wheel – I spent a lot of time developing clever ways of reviewing characters and words. I actually developed a simple spaced repetition system on my own and kept track of scheduling manually. Spending a few hours online reading about this would have helped enormously!

- Language exchanges are great – I’ve seen many negative comments about language exchange online, but I’ve met over 30 native speakers this way, and it’s been great for my learning. It’s also an excellent way to make friends if you’re not the extrovert kind who find it easy to chat with a random stranger. I haven’t experienced the language struggle people talk about; just divide the time evenly and it’ll be fine!

- Class size matters – The most important factor to consider when you choose which course to enrol in is the size of the class. With fifteen other students in the group, you will mostly speak with other learners and won’t get much individual feedback. If you’re in a group of five, you will get plenty of attention. I think 3-5 is the ideal size, but it depends on what you do outside class as well.

- Institutions hold ambitious students back – If you just go with the flow, you will learn much more slowly than you have the potential to. This is provided that you’re not working full time as an English teacher or just want to party all the time, of course. If you have the time, try to get into more difficult classes, where just surviving requires you to learn fast. While doing this, don’t neglect the foundations. You can deal with most of that outside class, though!

- Going to class is great, but it’s not enough – I have learnt an incredible amount of Chinese from my teachers and textbooks. Even though many of the articles on Hacking Chinese are dealing with problems when learning Chinese, I still think that classroom learning is very important. You just need to make sure you take responsibility for your own learning and cover the things you won’t learn in class.

Proficiency after my first year in Taiwan

I came to Taiwan knowing a lot of words and some grammar, but without really being able to say more than the most basic things. Listening was almost impossible. After the first semester, my parents visited, which meant a few weeks of travelling across Taiwan and having to use everything I had learnt. I wouldn’t say I was fluent back then, but I could use the language to achieve most practical things I needed.

After my second semester, my reading and writing improved a lot. Naturally, speaking and listening improved too, but still suffered from the common problem of not being practised enough. Looking back, it seems like I built advanced but narrow knowledge. I don’t think that was the wrong thing to do, but spending all that time learning to read newspaper articles definitely took time from basic speaking and listening.

Stay tuned

That’s it for this time! Next time, I will talk about my second year in Taiwan.

Tips and tricks for how to learn Chinese directly in your inbox

I've been learning and teaching Chinese for more than a decade. My goal is to help you find a way of learning that works for you. Sign up to my newsletter for a 7-day crash course in how to learn, as well as weekly ideas for how to improve your learning!

9 comments

Great post. Lots of valid points and things to be aware of when joining a study program.

Just being on one does not guarantee success. It’s the time spent out of class using and adapting what you learnt in class.

Thanks for the insight into your personal journey Olle. It is interesting how much can be achieved when you are motivated enough and put in the time.

I’ve been back in Australia since 2014 and my Mandarin has been gradually regressing while I work and complete further study here. My listening is still okay, but I have lost a lot of active vocabulary that I used to know. I might end up back in Taiwan to teach in another year or two and I am interested in applying for a scholarship and spending 6-12 months getting my Mandarin to where I would like it if I am going to live in Taiwan permanently.

A lot of it relies on the learner, but a positive learning environment and good teachers are a huge boost too. Without going to ICLP (too expensive) would you recommend Wenzao or anywhere else in Taiwan that you or others had experience with?

I am also interested in your input on the matter if you don’t mind Gwilym.

This is an interesting discussion I’ve had with several students. The structure and framework that a course offers is extremely valuable for most learners. It might not be for the professional polyglots, but those make up 0.01% of the population and are largely irrelevant. For the rest of us, courses are great, they are just not enough. So, there are two options if you live in Taipei (just a concrete example):

1) Go to ICLP

2) Go to Shida or simila

The first is roughly four times as expensive. This is wasted money if you are a disciplined and/or highly-motivated student. You can hire a tutor for many hours a week and still spend less money if you go to Shida. However, by going to ICLP, the minimum requirement of effort increases a lot, which matters for most students.

So, pay for as much structure as you need (which might be very little or very much). Use any remaining budget to pay for high-quality tutoring in areas your course doesn’t cover (enough). Fill the rest of the time with things you shouldn’t do in class (reviewing words, learning characters) and interaction with native speakers.

I should probably turn this into an article. 🙂

I know that I would definitely appreciate an article like that.

I think that I did learn a lot while in Taiwan because even though I was not consistent enough with my study. I went out of my way to immerse myself as much as I could. I believed that my approach was working well at the time. I thought all I needed was Anki, Pleco and trying to make local friends, with a few kung fu movies and dubbed animes thrown in for good measure. The problem was I was just not disciplined or consistent enough to maintain my peak levels of study I went through. Looking back I realise I could have made much greater progress with the pressure of a course in addition to my self-enforced cultural immersion.

I hope the second time works out slightly better.

I’ve never been to Taiwan, but some of my friends did and they had the best experience ever. I think the only obstacle here is when you go to China mainland because of the language.

Still, it’s a great psot, thanks for sharing your experience.

I’m not entirely sure what you mean, but I Had a great experience too (otherwise I wouldn’t have stayed and kept learning Chinese). However, there are major problems with how Chinese is taught, both in Taiwan and elsewhere. While going to class provides you with a basic structure, it’s far from enough, unless you go to a school that requires you to spend a lot of time on your own, such as ICLP or similar. Those institutions are really expensive, though, and you might be better off going to cheaper schools and just pay for extra tutoring.

Hey Olle, great post! What you are talking about is exactly my experience with Chinese. I am thankfully enrolled in a private school in the mainland that caters to Westerners. In seven months of learning (mostly through the GPA method), I feel comfortable traveling anywhere in China by myself.

Each of my classes is one-on-one so it forces me to interact. There is no one else to take the pressure off! At first it was tiring, but I have since come to love it! I am certainly not as motivated as you, and I’m certainly nowhere near any level of fluency; however, I can hold a conversation at a basic level for half an hour to an hour in Chinese. This has been deeply satisfying to me.

To me, it seems the most basic principle of language learning is finding opportunities to completely immerse yourself in that language. When my brain has no other option than to try to use Chinese, it will! And best of all, conversations offer context which makes it easier to remember words. For instance, today I just learned 乱七八糟. It was in the context of a conversation I was having with my cleaning lady. My apartment was a mess, and she used this word. I did have to look it up on Pleco because the meaning is idiomatic, but once I did, we both had a good laugh. It’s now stuck in my head because of that interaction.

You don’t seem to mention the colossal issue of the Taiwanese accent (correct next if I’m wrong). I have to say that aside from the opportunity to learn traditional characters I’m extremely dissatisfied with my Taiwanese language learning experience. Even my Taiwanese friend who is a Sinologist says that the Taiwanese speak inferior Chinese, which makes sense considering their history with language. It’s not just the accent, which could probably be compared to an Alabama accent or something equally strong and slurry, but a very superficial understanding of the language and a lack of creativity with the language that stems from that lack of understanding. Then there is the issue of failed attempts to speak standard Chinese to Chinese-learners which most often results in a version of Chinese that somehow is even more confusing and removed from standard Mandarin than the Taiwanese accent. Furthermore, there is the issue of a majority of older Chinese basically only being able to speak Chinese as a second language, if at all, and we all know that old people are normally an invaluable resource to language learners. Taiwan is great in many ways, but I can just roll my eyes ten times over when I hear it advertised as a great hub for learning Mandarin. From what I’ve seen and heard, it’s a great hub for learning bad Mandarin. Mainland China may not be the place to use Facebook and YouTube, but it is still the place to learn beautiful Mandarin, of course. Anyway, my Chinese only really started to improve when I found mainland Chinese language partners online. I’m not questioning your abilities here by the way- I’m sure you speak excellent Chinese- I’m only saying that for many learners in Taiwan this will really be a problem, whether they know it or not.

My experience after four years in Taiwan, studying at four different institutions, is very different from yours. The accent is much less of a problem than you make it sound, at least for the majority of people I know. Rather than being “slurred”, it’s actually a lot clearer than many northern (e.g. Beijing) accents because they don’t reduce syllables as much and use erisation less. Naturally, it will differ a lot depending on who you speak to, but accent has rarely been an issue for me, at least no more than it is in other areas. The problem of accent will arise regardless of where you learn Chinese, including Beijing. Very few people follow the standard anyway, and even the standard is just an accent that has official recognition.

The Taiwan standard differs a bit from the mainland one, but typically not enough to make it a practical problem. I usually tell students that it’s a little bit like the difference between General American and Received Pronunciation in terms of how hard it is to understand (i.e. no difficulty at all) and that the difference in vocabulary and grammar are on a similar level to American and British English as well (this is based on my own experience, not a quantified comparison, which would be very hard to make). As noted, not all people speak according to the standard, but again, that’s true anywhere.

I don’t even know where to start with “a very superficial understanding of the language and a lack of creativity with the language that stems from that lack of understanding”. I find it hard to take such a statement seriously.

I’ll keep recommending Taiwan as an excellent place to learn Mandarin. Is it the best place to learn? That will depend on many factors, and accent, traditional characters and so on are all part of the equation when choosing where to study, as are many other factors such as quality of life, quality of institutions and a myriad of other things.