From 李纯博’s 雨天.

For people who are learning languages other than Chinese, the question of how to improve handwriting doesn’t come up often. Some people are interested in penmanship and calligraphy, but that’s beyond writing merely to communicate, more art than language.

For people who are learning Chinese, there are a lot of things to say about handwriting. In this article, I will cover most of them, albeit briefly in some cases. Here are some of the questions that I will answer:

- Do I need to learn to write by hand?

- What skills does handwriting in Chinese require?

- How do I improve my handwriting?

- What resources are there to help me learn?

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to this article:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcast, Overcast, Spotify and many more!

Why handwriting in Chinese is hard

Let’s start with the basics in case you’re new to learning Chinese. Almost all languages use a phonetic script, meaning that the written word reflects the pronunciation of the spoken language. The most familiar way for most readers ought to be the Latin alphabet I use to write these words, but even seemingly complicated scripts like Arabic and Korean are phonetic as well.

Chinese, on the other hand, uses characters, which were created in many different ways. The basic characters have nothing to do with pronunciation, but are instead depictions of objects, called pictographs. More complex characters often do include clues about how they are pronounced, but these require an advanced level to make full use of and are just that: clues. This means that to read and write Chinese characters at a near-native level, you need to learn many thousands of characters. For more about how the Chinese writing system works, please check out the series of articles starting with this article:

The building blocks of Chinese, part 1: Chinese characters and words in a nutshell

Handwriting Chinese characters is extra tricky because of the large number of unique components and the even larger number of combinations of these components you need to keep track of. Recognising a character in context, such as when reading, is much easier than writing the same character by hand. It’s perfectly possible to be able to read well, but not be able to write much by hand at all, and this is indeed quite normal. Native speakers typically spend a, for us, unimaginable amount of time learning to write characters, which both impractical and difficult to match as a second language learner.

So, in essence, if you can read and type French, you can write it by hand, but knowing how to read and type in Chinese does not mean that you can write by hand, and learning to do so would be a major undertaking.

Is it necessary to learn to write Chinese characters by hand?

Given the amount of time it takes to learn to write by hand, do you really need handwriting? Since the most popular input systems on phones and computers rely on how the characters are pronounced, can’t you just skip handwriting altogether? This depends on your goals. If your goal is to learn only spoken language, then skipping handwriting, or indeed writing altogether, is not a problem.

However, most students want to learn to read and write too, although to a more limited degree. That means that you would know how to say more things than you could write, for example, which seems to be the most natural way to me. I have argued elsewhere that delaying character learning should be the default option in most cases, see for example Should you learn to speak Chinese before you learn Chinese characters?

Should you learn to speak Chinese before you learn Chinese characters?

It also seems natural to be able to write fewer characters by hand than you can type, but this doesn’t necessarily mean that you should skip handwriting altogether. I think all students who want to learn to read and write Chinese characters should also learn to write by hand, not because it is practically useful (it usually isn’t, even if you live in a Chinese-speaking environment), but because it helps you understand Chinese characters. It’s up to you to decide if that means learning 100, 1,000 or 5,000 characters. Read more here:

What you need to write a Chinese character by hand

Still here?

Okay, let’s continue by looking at what writing a Chinese character required in terms of knowledge and skill. Success depends on being able to:

- …recall which character to write out of several possible options, e.g. recalling that it should be 工作 (gōngzuò) and not 工做 (gōngzuò). It could be argued that this is one of the more challenging aspects of learning Chinese characters, which I have done here: The real challenge with learning Chinese characters.

- ...recall the components the character is made up of, e.g. recalling the character that 想 (xiǎng) is composed of 心 (xīn) and 相 (xiāng), which is itself made up of 木 (mù) and 目 (mù). This is best solved by knowing the meaning of commonly recurring components and using mnemonics to connect them.

- …recall the relative placement of the components, e.g. recalling that it’s 能够 (nénggòu) and not 能夠 (nénggòu). This can be very tricky! Both the examples are actually correct, but the former is correct in simplified Chinese and the latter in traditional Chinese. I wrote an article about characters that share the same components but are still different.

- …recall what strokes each component is composed of, e.g. recalling the difference between 千 (qiān) and 干 (gān). Naturally, most of the time, using the wrong stroke won’t turn the character into a different character, it will just make it look a bit odd or wrong to an experienced reader.

- …recall the properties of the strokes, including their length, placement, order and direction. A classic example is 己 (jǐ) 已 (yǐ) and 巳 (sì). Numerous examples of correct writing and errors arising from incorrect length, placement and direction can be found in this article: Handwriting Chinese characters: The minimum requirements. This problem is made worse by the fact that the correct way of writing often varies. For example, on the mainland, 起 is written with 己, but in Hong Kong and Taiwan, the standard is to write it with 巳 instead. How 起 itself looks on your computer screen right now depends on what font is being used. Also, as if all this wasn’t enough, don’t forget about stroke order!

- …form a mental image of the character combining all these things and commit it to paper by using a writing instrument such as a pencil. This is the actual writing, the penmanship. With some practice, all students can do this well enough to be able to communicate in writing, but whether you do it neatly or beautifully is another question, one that we will return to later in this article.

As you can see, this is more complex than writing by hand in other languages, where handwriting is mostly a slower and, at least for some, more frustrating way of typing. If I can type a word in English, I know how to write it by hand. This is not true in Chinese, where typing merely requires you to recognise a character, whereas handwriting requires much more, as I have just shown.

Intent, then execution

When it comes to improving handwriting, it helps to separate intent and execution:

- Intent refers to what you want to write, it is your mental image of the character, based on exposure to the written form, knowledge about the character and knowledge about characters in general.

- Execution is what you actually write, which is never exactly what you had in mind, which becomes painfully obvious for most when they write the first few characters. It looks easy, but writing neat characters is really hard, even if you know perfectly well what they look like!

To illustrate with an example, I know very well how to write the character 想 (xiǎng) and you probably do too. But does the character come out the way you intend every time? Probably not, unless your penmanship is already on an expert level. You’ll be able to spot things you didn’t write intentionally. Perhaps the 木 takes up too much space, or the bottom of 目 extends to far down, or the dots in 心 accidentally touch the hook. You didn’t intend for that to happen, yet it did. If you write the character again, you might or might not get the same result.

The point is that intent is much more important than execution!

Having a correct mental image of the character (intent) requires learning things about Chinese characters, but penmanship (execution) merely requires more practice, i.e. writing more by hand.

Compared with speaking and pronunciation, it’s often easier to tell the difference between a mistake (a problem with execution) and an error (a problem with your mental image). For example, if you intend to write 目 (mù), you won’t write 日 (rì) by accident, and if you intend to write 木 (mù), you’re unlikely to write 未 (wèi) instead. If you do, I would take that as a clear sign that you probably don’t know the characters very well, so that’s a problem with intent, not execution.

As a counter example, if you write 未 (wèi) instead of 末 (mò), or 已 (yǐ) instead of 己 (jǐ), that could very well be sloppy writing. I can’t know by looking at a single handwritten character whether you just accidentally put the pencil down too early (a problem with execution) or if you don’t know how to differentiate these characters.

The bottom line is this: If you intend to write the wrong character, it will turn out wrong every time you try to write it, no matter. If you intend to write the correct character, it might come out wrong because of imperfect execution, but simply practising more will fix this problem. I wrote more about intent here:

What you intend to write is more important than the character you actually write

Target models for Chinese characters

When you start learning Chinese, it’s important that you have models to mimic that are actually correct, or at least models that adhere to the standard in whatever region you’re focusing on. This is true for spoken Chinese and pronunciation as well, not just handwriting. Your teacher and textbook probably make an okay job of this, although there will always be some inconsistencies.

Today, however, most people study Chinese using their phones and computers. When you do that, make sure you have proper fonts installed. This will avoid a lot of confusion later and is well worth spending some time on as you start out. I didn’t do this when I started learning Chinese, but soon realised that I had actually learnt Japanese standard for many characters, because that was what my computer used by default!

I have written two articles to help you sort out font issues:

These are computer fonts, though, and aren’t ideal for handwriting practice. In this guest article, Harvey Dam talks specifically about handwriting. The article is full of actual examples with real handwriting (not computer fonts) and should be studied by anyone who cares about handwriting!

How to practice execution

Assuming that you know what the correct character looks like, how can you improve your execution, or your ability to transfer your mental image to paper using a pencil? The answer of course depends on your current level, but I’ll give some general advice:

- Use grid paper – This is particularly useful for beginners since it gives you clear guidelines for how big the character is supposed to be, and it’s much easier to compare the proportions of different components, especially if the model you use also uses a grid. There are many tools to generate grid paper for Chinese characters, but here’s one. For resources that also include stroke order and the like, check this article instead. I have also included some resources at the end of this article.

- Get feedback – As is usually the case when learning languages, getting feedback is essential. While you will be able to spot some mistakes yourself, there will be things you’re doing wrong that you’re not even aware of. When starting to learn Chinese characters, it’s hard to fully understand how complex the writing system is, and if you care about getting it right, you really need feedback.

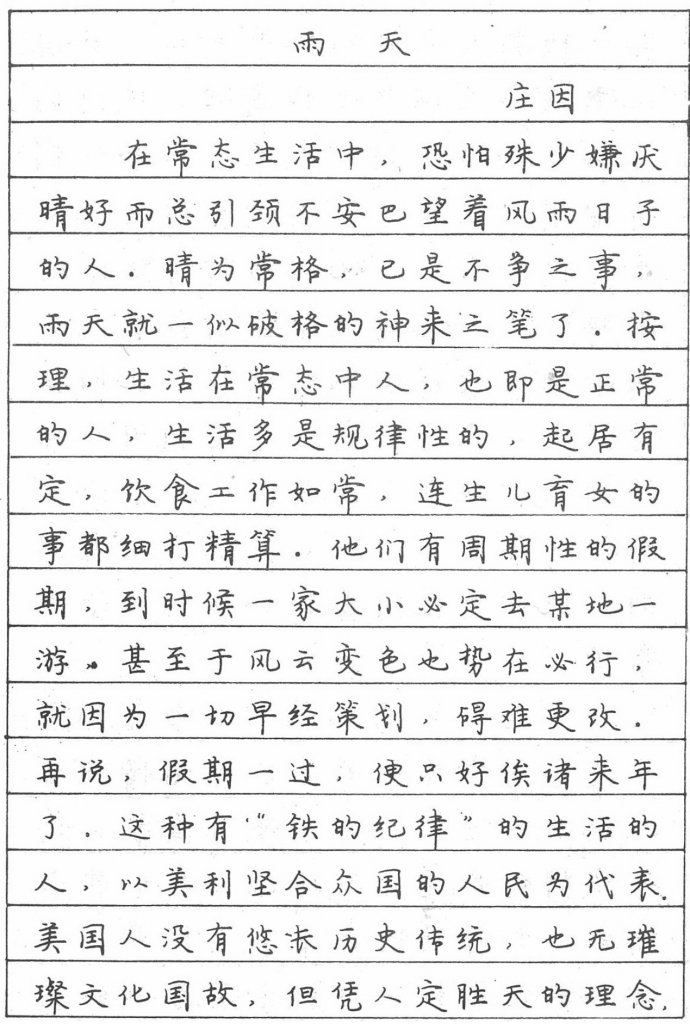

Mimic a target model – This is only good advice if you want to improve the way you write, not whether you remember the characters or not. Find someone who writes neatly (preferably approved by a native speaker so you don’t pick anything too far out) and mimic the way they write. I’ve pasted an example (right) from 李纯博’s 雨天.

Mimic a target model – This is only good advice if you want to improve the way you write, not whether you remember the characters or not. Find someone who writes neatly (preferably approved by a native speaker so you don’t pick anything too far out) and mimic the way they write. I’ve pasted an example (right) from 李纯博’s 雨天.- Practise, practise, practise – If you want to improve your Chinese handwriting, you need to practise. You need to care about the way it looks, you need to spend the time writing the characters, not just with the aim of getting them down on paper as quickly as possible, but to do so more neatly than last time.

- Spread it out – As is the case with most forms of learning, including motor skills such as penmanship, it’s more beneficial to space your practice than to mass it. That means that practising a little bit every day is better than doing one long session every month.

Resources for learning or improving handwriting

There are many apps, websites and books about handwriting and Chinese characters. This is not meant to be an exhaustive list of all resources I am aware of, but is rather meant to include a few helpful resources of each kind. For more, check Hacking Chinese Resources.

Standard references for stroke order

- Simplified characters (Mainland): 现代汉语通用字笔顺规范 (there is no online, searchable edition)

- Traditional characters (Taiwan): 常用國字標準字體筆順學習網 or 國語辭典 (both online and searchable)

- Traditional characters (Hong Kong): 香港標準字形及筆順 (also online and searchable)

- 汉典 does a good job of comparing standards; just search for a character and scroll down to 字形对比 (see one example for 起 below)

Information about characters (i.e. dictionaries, see separate post)

- Pleco – Mobile app (free and paid)

- Hanping – Mobile app (free and paid)

- Outlier Linguistics – Character etymology and more (paid)

- Wenlin – Character information (paid)

- 漢典 – Online dictionary (free)

Handwriting practice

- Hanzi Grids – Generates printable worksheets (free and paid)

- Incompetech – Various tools for generating worksheets (free)

- 书法字典 – Search calligraphy for specific characters (free)

Apps for practising handwriting on-screen

* Please. note that I work for Skritter, but that I’ve recommended the app long before I started doing that.

The place of handwriting in your overall strategy for learning Chinese

As a beginner, you probably don’t need to think too much about how handwriting fits in the larger scheme of things, but as you progress, you need to ask yourself what you want handwriting for and then devise a strategy that suits your needs.

For example, I teach Chinese, and value the ability to write most commonly used characters for that reason. I hardly ever write by hand in other situations, so if it weren’t for the teaching bit, I would spend less time on handwriting. I came up with a rather simple method to achieve my goals, yet spend as little time as possible on handwriting.

Here’s a summary:

- Reading gives me passive recognition of frequently used characters. Reading a lot is good for many other reasons, of course.

- Typing forces me to more actively select the correct character among alternatives, doubly so because my input method in Linux is pretty bad and often chooses the wrong characters.

- Skritter helps me withe active recall for less commonly used characters by way of spaced repetition, which is by far the most time-efficient way of reviewing rare characters.

- Handwriting input on my phone replaces typing occasionally and embeds handwriting in real-life communication. I also get immediate feedback, albeit a bit crude.

This method works for me, but it might be overly ambitious for you! Or it could be that you care much more about handwriting than I do, in which case my approach will be inadequate. I wrote more about my minimum-effort approach here:

A minimum-effort approach to writing Chinese characters by hand

Your method

What does your approach look like? How important is handwriting to you? Leave a comment!

Interested in how to learn to read other people’s handwriting? Continue reading here:

https://www.hackingchinese.com/learning-read-handwritten-chinese/

Tips and tricks for how to learn Chinese directly in your inbox

I've been learning and teaching Chinese for more than a decade. My goal is to help you find a way of learning that works for you. Sign up to my newsletter for a 7-day crash course in how to learn, as well as weekly ideas for how to improve your learning!

3 comments

Care must be taken when selecting support for character learning: in cases where the character fonts are based on simplified character sets, the tendency is to introduce systematic errors, i.e. to replace the correct full-form character with a simplified one. This affects dictionaries, books about character writing and apps. For example, Shanki (mentioned above) replaces the correct full-form character 從 with the simplified one, even when full-form (traditional) characters are selected.

It is easy to choose bad models but nearly impossible to overcome their bad influence, and for those wishing to learn full-form characters, the field of Chinese learning is full of such traps.

In short, don’t believe the claims of any supposed support to writing characters without independent verification.

I would really like to see something on how to read Chinese handwriting! I have a degree in Mandarin but we all learned to write in print style, and never had to read a single word of hand-written Chinese. When I went to work in China I was frequently given hand-written notes which I had to try to read. There is almost nothing out there on the net, or in books.

You mean, such as this one: Learning to read handwritten Chinese? 🙂