Spaced repetition is very powerful compared to massed repetition, which is why software utilising the spacing effect is growing ever more popular. I sometimes feel like an SRS missionary, writing articles about why everybody should start using SRS and which program I prefer myself (if you don’t know what SRS is, please read these articles before reading this one). This is all very good, but it leaves many questions unanswered. For instance, how should spaced repetition software be used?

In this article, I will discuss how to review vocabulary using SRS, including how to use the various answer buttons and some other functions commonly available. I will use Anki for all examples, but other good programs will of course have similar or indeed identical features. The algorithms used to calculate the spacing between repetitions might not be identical for all programs, but they are similar. What I discuss in this article is useful beyond specific programs, so don’t put too much emphasis on the exact details.

In this article, I will discuss how to review vocabulary using SRS, including how to use the various answer buttons and some other functions commonly available. I will use Anki for all examples, but other good programs will of course have similar or indeed identical features. The algorithms used to calculate the spacing between repetitions might not be identical for all programs, but they are similar. What I discuss in this article is useful beyond specific programs, so don’t put too much emphasis on the exact details.

This article isn’t meant to be a guide to what is correct, it’s rather meant to be a discussion with some personal examples and motivations to why I’m doing what I do. If you have other ideas or don’t agree, please leave a comment!

More about spaced repetition on Hacking Chinese

- Why flashcards are terrible for learning Chinese

- Why spaced repetition software is uniquely well suited to learning Chinese characters

- Diversify how you study Chinese to learn more

- When spaced repetition fails, and what to do about it

- Should you focus on learning Chinese words or phrases?

- About cheating, spaced repetition and learning Chinese

- Three ways to improve the way you review Chinese characters

- Flashcard overflow: About card models and review directions

- If you think spaced repetition software is a panacea you are wrong

- Is your flashcard deck too big for your own good?

- Towards a more sensible way of learning to write Chinese

- You can't learn Chinese characters by rote

- Measuring your language learning is a double-edged sword

- Answer buttons and how to use SRS to study Chinese

- Chinese vocabulary in your pocket

- Dealing with tricky vocabulary: Killing leeches

- Spaced repetition isn't rote learning

- Anki, the best of spaced repetition software

- Spaced repetition software and why you should use it

Answer buttons

Most programs make use of four buttons, typically labelled:

- “again”

- “hard”

- “easy”

- “very easy”

Without any kind of definition, these answers are completely arbitrary. Do you hit “again” even if you fail a minor point in an otherwise complex and completely correct answer? Do you hit “easy” or “very easy” when you encounter a word you feel that you know quite well? What’s the difference between “hard” and “easy”? Of course, there are no entirely correct answers here, but I will give you my own ideas. Before that, though, let’s discuss briefly why this matters at all.

The short answer is that the choice matters greatly in the long run. Even if the algorithms will more or less automatically adjust the difficulty and the intervals for you, make sure you’re not being too harsh. A quick calculation shows that if you could use “very easy” for 10% of the cards instead of “easy”, you will save many hours over a year of reviewing (how much you save depends on how much time you spend reviewing of course). This time could have been spent doing something more useful. However, the opposite is true as well. If you select “very easy” for cards you don’t know that well, you will end up failing them, thus wasting more time than you would have saved, so don’t be too lenient either.

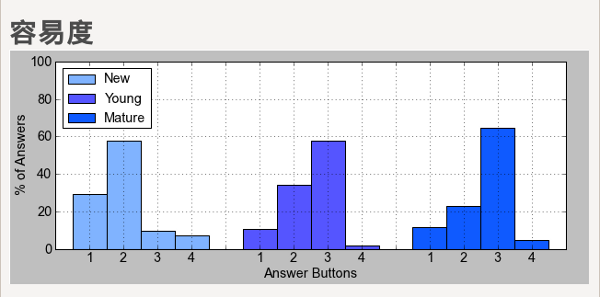

What does all this mean, then? It means that you should assess your answers as accurately as you can. This is individual to a certain degree and requires a bit of practice. If you use a decent program, you should be able to get detailed graphs showing you how much you click the various alternatives. Here’s what my graph looks like:

Avoid perfectionism: 90% is good enough

Note that most algorithms are set to give a 10% failure rate, which is almost exactly what I have if we ignore new cards. This is because a higher rate would mean that you’re wasting time studying too many words you already know, so don’t make the mistake of thinking that a higher number is necessarily better. Perfectionism is a waste of time. If you fail 10% of the cards, you’re doing it right!

Now, most of this is self-adjusting. If you enter a bunch of difficult words, you will hit “hard” quite a lot (check my new cards, for instance). However, since the intervals of these cards will be shorter because of that, you will also learn them better, which means the interval will be adjusted so you think they are “easy” next time you see them. This is the whole point.

The answer buttons and how I use them

Here’s what I usually do (including approximate percentage for mature cards):

- “again” (~10%) – I really don’t know the word, or I have forgotten a crucial part of it (such as forgetting the pronunciation of a character or only having a vague idea of what it means). However, the nature of the mistake is important. If it’s something I think it’s likely I will remember next time, I might choose “hard” rather than “again” for relatively new cards (interval less than one month). The reasoning behind this is that it will just clog the review queue if I reset the interval by hitting “again”. If I make the same mistake next time, I will choose “again”. I’m convinced this saves quite a lot of time in the long run.

- “hard” (~20%) – I select this answer if I can come up with the right answer, but only after considerable mental effort, such as retrieving old mnemonics or comparing with other words I know. Also, see the discussion above about using “hard” instead of “again” for mistakes that are unlikely to occur twice. I never use this for words that have longer intervals (months or years), because you simply won’t see them again for a long while even if you choose “hard”.

- “easy” (~65%) – This option is for cards that I recall almost instantly or feel very familiar with. These are words that wouldn’t stop me when I’m reading and don’t require much mental effort to recall. I estimate that I spend less than three seconds each on these cards; if more, they count as “hard” rather than “easy”.

- “very easy” (~5%) – I only use this answer when I’m completely sure that I won’t forget this word within the given interval. For new cards, it means that I have learnt it properly and really think that the current interval is much too short and is a bit wasteful. For old cards, I answer “very easy” for anything I’m sure I’d know years from now even without reviewing. Instant or intimate knowledge of the word is what generates “very easy” for me.

Look at the interval

I think it’s a mistake to be 100% consistent when reviewing vocabulary if you ignore the intervals and only look at the buttons themselves (“again”, “hard” and so on). There is a huge difference between “hard (4 days)” and “hard (4 years)”. The reason is that I can easily pick the first one if I make an easily correctable mistake on a new word because I know I will be checked again in a few days anyway. If I fail again because the correction wasn’t as easy as I imagined, I will know that and can hit “again” if I feel the interval has grown too large. If the interval is four years, however, I won’t see the card ever again (in practical terms) even if I choose “hard”, which means that I can’t be sure I’ve corrected the mistake. In this case, I would hit “again” and suck it up.

Other useful functions

There are many other features you should use to increase efficiency further:

- Leeches are cards that drain time because you fail them over and over. Anki suspends these cards automatically after a given level. I suggest lowering this level (the default number is 16), because if you fail a card that many times, you really need to do something else. As I’ve argued elsewhere, spaced repetition is meant to reinforce what you already know, not force new knowledge through cramming. Please also refer to my article about killing leeches.

- Suspending cards simply means that you manually remove them from the review queue and that they won’t appear until you activate them again. I do this for cards I suspect have serious problems or when I think that reviewing them is useless, perhaps because I’ve given too little information and might confuse the word with other words.

- Marking is something I’ve started doing a lot recently, which basically means putting a tag on the word that you can easily find later. I separate active vocabulary learning from reviewing, both in time and space. I review using my phone, but I always use my computer to kill leeches, delve deeper into difficult words or sort out synonym issues. Therefore, while reviewing, I simply mark any card I might need to work more with and keep reviewing. Then, I go through these words later, using dictionaries, asking native speakers, correcting mistakes.

Some questions for the reader

- Are your answering criteria different from mine?

- What does your graphs look like for new/young/mature cards?

- Do you use leeches, suspending and marking as I do?

- Do you use any other cool tricks I haven’t mentioned?

- Any other tips, tricks or ideas you’d like to share?

Tips and tricks for how to learn Chinese directly in your inbox

I've been learning and teaching Chinese for more than a decade. My goal is to help you find a way of learning that works for you. Sign up to my newsletter for a 7-day crash course in how to learn, as well as weekly ideas for how to improve your learning!

15 comments

So you only use anki to review vOcab? What about sentence patterns or the cloze deletion method? Such as suggested on sites such as ajatt. Do these methods make sense to you?

I have some grammar patterns in there as well as well as some phrases I find interesting or difficult. I also have a separate deck for memorising 道德經. I don’t have a deck based on sentences and cloze deletions, though. The reason isn’t that I disapprove of other methods, indeed I think using sentences might work very well (I’m trying it out with 成語), but there is simply no way I can turn my current deck into sentences, much less MCDs, ajatt style. I have around 21 000 cards, so any systematic change would be impossible.

I think the main advantage of having just words is that it’s much, much quicker, both when reviewing and when adding (finding the right sentences is sometimes very hard, especially if you don’t know the key words you’re supposed to learn. How do you know the sentence you’re using is good? I prefer to rely on massive volumes of reading and listening to pick up context. This is perhaps not ideal, but it seems to work pretty well.

What I could do is try using sentences from now on with new words I learn. That would enable me to form an opinion about what it’s like. That won’t mean I change my main method to this, but that’s mostly a question of momentum. In short, I think all methods mentioned are sound, at least in theory. The reason I haven’t written about this in more detail is because I haven’t formed an opinion about the question yet!

One distinction I use when reviewing is literary vs. conversational Chinese (my deck has quite a bit of both). If it’s literary Chinese, I am not terribly concerned with getting the pronunciation right, and focus mostly on remembering the meaning. If it’s a conversational word/phrase, I am MUCH more likely to hit again or suspend over a pronunciation mistake.

Excellent point, Sara. I do this as well and can think of some situations:

1) Characer parts (i.e. learning how to pronounce some radicals is useless, I hit “hard” rather than “again)

2) Classical Chinese (I don’t have much of this, but there is still some; I don’t need to read this aloud)

3) Very formal vocabulary (your example, but the problem is that it’s hard to know what’s formal enough, so to speak)

4) Very rare vocabulary (enough to just understand, perhaps similar as the previous situation, although rare and formal aren’t necessarily the same)

Partly out of habit, and partly because it suits me just fine and I don’t want to spend time on switching to Anki just for the extra bells and whistles, I use Mnemosyne.

Recently, I tried an experiment by creating a separate category of cards within my deck. The only difference with the other cards is that I would systematically rate my response a “2” (out of 5), regardless of the strength of my recollection. With Mnemosyne, a “1” will almost make you start anew with a card, while a “2” will simply reduce the interval before the card comes up again.

With Mnemosyne’s algorithm at least, I have found that the interval between reviews is not dramatically affected by choosing “2” instead of say “4”. I am making up an example here, but rating a card “2” might make it show up say 21 days later, whereas a “4” would give you a 34 day interval. With each review, regardless of the rating, the individual intervals get longer and longer – but cards rated 2 are simply scheduled to come back earlier.

Now, I know the theory behind SRSing is that for maximum reinforcement, you should only review a card when you are on the cusp of forgetting it – this is not only to reduce the total number of reps over time, but also because the extra effort involved in successfully retrieving an answer from your memory will have a reinforcing effect. (This is my understanding of it anyway.)

However, I have personally found that my special category of “always-rate-them-2” cards have impressed themselves on my memory more thoroughly. The added repetition is not so much that they ever get boring or crop up too often for my taste ; and the whole process is not more time-consuming because my recall is quicker and more effortless. I can go through a deck faster, and tend to avoid my daily reviews less often (not at all in fact).

So, although this is unorthodox, I have decided to use this same method with all my cards. As I mentioned before, this does not have the effect of freezing my reviews in time, since the intervals do get longer – it just happens more gradually.

Perhaps I am an anomaly, but I would suggest trying “systematic two-ing” as an experiment to those who are intrigued by the idea.

I actually have tried this before, and for me, it is definitely not the most efficient method. While I was able to keep my queues to zero, it took a lot of time. I can get the almost the same results (as far as remembering stuff) by choosing the interval based on difficulty as Olle describes in this post with a lot less time spend on reviews.

Interesting comment! I have a couple of things to say. First, the numbers you give for your experiment are roughly similar to what they would be in Anki and I did some calculations prior to writing this article and ended up with the same figures, but with a completely different conclusion. Decreasing the review interval with 38% (using your numbers), which means that you reduce review time by the same amount. For all cards in a year of studying 40 minutes per day, this would save 244 hours. Naturally, this isn’t relevant for all cards. I mentioned 10 hours, which is because the difference was less than 38% in my case and I only assumed that it was relevant for 5% of the cards, which ends up close to 10 hours. I think this is quite a lot of time. In ten hours, I could learn several hundred characters. Perhaps our perspectives are different.

Second, I don’t think you’re observation about better recall is weird or that your approach is unorthodox. What you’re doing is aiming for more than 90%, which is something I wouldn’t do, but which is perfectly fine to do if you know what you’re doing. Remember that the goal with SRS isn’t to learn all the words, it’s to learn the words as efficiently as possible given a 90% recall rate. So, it’s fairly obvious that you will get better results from reviewing more often (I haven’t heard or read about what you say about memory being reinforced when trying to recall something which is close to being forgotten, do you have a reference for this?). The question isn’t if it works or not, the question is if it’s worth the extra time.

Finally, I think it’s great that you conduct these experiments! This is what everyone should be doing. I’d be delighted to read about other experiments you’ve tried.

Another significant point is:

SRS should not be the only time you review vocabulary/grammar/whatever. In my opinion, it should not even be the main way to review vocab etc.

The main way I review language is actually reading/listening to stuff in Mandarin. Everytime I understand a word in context, it’s a review. I consider SRS to merely be a support. If I relied on reading/listening alone for review, then there would be words where the intervals would be to long between encounters. I use SRS to fill most of this gap (as you say in the article, trying to completely fill in the gap is inefficient), and to me, SRS is just that – a fill-in. That might be why I found the press-2-only method to be inefficient – I am actually reviewing most words far more often than they appear in my SRS, so increasing the frequency of SRS reviews for words which are not actually hard/rare is excessively redundant.

Excellent point again. I have mentioned this in other articles about SRS, but perhaps I should have mentioned it here as well. I spend quite a lot of time with Anki, but I spend much, much more time listening to the radio, watching various broadcasts and reading books. This is also review. More importantly, over time, exposure to audio and text will generate knowledge about how words are used, something I think is tricky to incorporate into SRS practice (although of course it can be done with sentences and so on).

Fair point on the “hard (4 years)”. In my opinion, this is really a shortcoming of Anki (or any other SRS that would do the same): once you reach months and years, the intervals just stop making sense.

-The hard button is always too high, but using “again” will just be such a loss of time (because perhaps I would be happy having the word in 1 week, and not having to redo it from the start.

-The easy/very easy intervals start being so long that it’s quite unlikely that I’ll ever see the card again (I don’t think my deck can live 5 years..). What I’d be more happy with (but I’m too lazy to implement it) would be to have a way to tell Anki “give me intervals that will make me review 20mn per day”. If I have less than that in a day, give me more to complete those 20mn, if I have much more, find a way to even it out. As far as I know, there is no “practical” way to do that, at the moment.

Other than that, I use globally the same strategy as you do. I coincidentally also started using marking to kill leeches once I’m back home, and it has proven to be very efficient.