Analysing and balancing language learning is important whether you’re an independent student or a teacher. If you’re a student, no one else can tell you what you need to do to reach your goals, at least not without knowing a lot about your situation. In most cases, that means that you have to do it yourself. If you’re a teacher, you need to make sure that your students are investing their time and energy wisely.

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcast, Overcast, Spotify, YouTube and many other platforms!

There are many ways of analysing and categorising learning activities, something I have talked about in an earlier article where I brought up the four skills (listening, speaking, reading and writing), the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (reception, production, interaction and mediation) and Paul Nation’s four strands (meaning-focused input, meaning-focused output, language-focused learning and fluency development). For an overview, please check this article: Chinese language logging, part 2: A healthy, balanced diet of Mandarin.

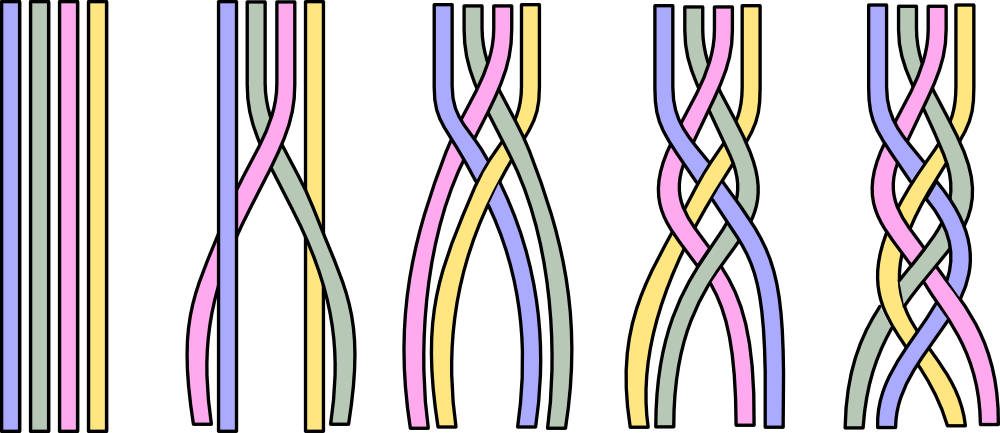

Paul Nation’s four strands: a model for balancing language learning and teaching

In this article, I want to look closer at the Four Strands and see how you can use them to balance your own learning (or that of your students if you’re a teacher, of course). I have used this model for many years, both when planning my own courses and when coaching students. It’s also included in Unlocking Chinese: The ultimate course for beginners, where I use it to explain how you can use the Four Strands to plan your learning.

Paul Nation published his article The Four Strands in the International Journal of Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching in 2007, and it has been widely used and cited since then (it has more than 750 citations on Google Scholar, for example). Still, in my work with professional development for language teachers, I’ve found that even most teachers aren’t familiar with the model, let alone most students. This is a pity, because it’s easy to understand and, if implemented, have huge positive impacts on the way languages are learnt and taught across the world.

In this article, I will explain what the four strands are and how you can use them to analyse and balance your own learning. If you want a more complete justification for each of the strands, please read Nation’s article (full reference at the end), but as far as I know, it’s not freely available.

Before we get started, it’s worth discussing what this model is for and who is meant to use it. It’s mainly meant as a tool to plan language courses and curricula, not the learning of individual students. If you’re a student yourself, you can of course use it and think of your own learning as a course with one student. In a way, the four strands work even better on an individual level, because one of the problems when trying to apply the model to a whole class is that the uneven language proficiency among students will make it very hard to satisfy everybody.

A quick breakdown of the four strands and what they imply

Let’s have a look at each strand very briefly first and discuss some overall points before describing each in more detail.

Let’s have a look at each strand very briefly first and discuss some overall points before describing each in more detail.

- Meaning-focused input – Listening and reading language you’re mostly familiar with, with a focus on understanding the content, as opposed to learning new words or grammar.

- Meaning-focused output – Speaking and writing using language you’re mostly familiar with, with a focus on conveying meaning, as opposed to using words you just learnt or practising a specific grammar pattern.

- Language-focused learning – Explicitly learning about the language (characters, vocabulary, pronunciation, grammar, etc.), plus input and output where most of the language isn’t familiar.

- Fluency development – Any language activity where you encounter nothing or almost nothing you aren’t familiar with. The goal is only to get better at using what you’ve already learnt. The focus is on meaning.

There are a few important things to discuss here that might not be apparent if you haven’t read Nation’s article carefully or applied the four strands in a real learning or teaching situation.

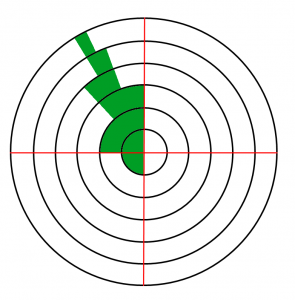

The four strands are equally important – Even though Nation admits that the exact weighting of each strand is somewhat arbitrary, he still maintains that they should have equal weight. I personally don’t agree with this statement, because I think input is more important than he thinks, and I often advocate high-volume listening and reading practice. Still, even if you aim for some other distribution than 25% for each strand, the model is still useful. I’ve written about the importance of input many times, but this article is probably the most direct argument in favour of input: Is speaking more important than listening when learning Chinese? When it comes to reading, check out: An introduction to extensive reading for Chinese learners.

The four strands are equally important – Even though Nation admits that the exact weighting of each strand is somewhat arbitrary, he still maintains that they should have equal weight. I personally don’t agree with this statement, because I think input is more important than he thinks, and I often advocate high-volume listening and reading practice. Still, even if you aim for some other distribution than 25% for each strand, the model is still useful. I’ve written about the importance of input many times, but this article is probably the most direct argument in favour of input: Is speaking more important than listening when learning Chinese? When it comes to reading, check out: An introduction to extensive reading for Chinese learners. Three strands focus on familiar language – Only language-focused learning includes intensive reading and listening, which is when you tackle difficult texts and try to learn about the language explicitly. This is radically different from almost all Chinese courses I’ve ever taken or heard about. If you study Chinese at university or at a language school in China, you’re likely to have almost all your classroom time filled with language-focused activities. This will lead to what I’ve called an illusion of advanced learning: The illusion of advanced learning and what to do about it.

Three strands focus on familiar language – Only language-focused learning includes intensive reading and listening, which is when you tackle difficult texts and try to learn about the language explicitly. This is radically different from almost all Chinese courses I’ve ever taken or heard about. If you study Chinese at university or at a language school in China, you’re likely to have almost all your classroom time filled with language-focused activities. This will lead to what I’ve called an illusion of advanced learning: The illusion of advanced learning and what to do about it.- Three strands focus on meaning – Apart from the first two strands, which have “meaning-focused” in their names, fluency development is also meant to be meaning-focused. There’s plenty of research that shows that meaning-focused activities, i.e. where the focus is on making sense of something or making yourself understood, are both more effective and more motivating for students. This is again in stark contrast with most activities presented in textbooks and language courses, which typically don’t focus on meaning, but are instead focused on form (correct writing, spelling, pronunciation, grammar, etc.).

All time counts, not just time spent in a classroom – While Nation’s article is addressing language teachers, he doesn’t say that each lesson should be balanced in terms of the four strands, or not even that classroom time in general should be. Naturally, some activities are better performed outside the classroom, such as meaning-focused input or fluency development (especially for listening and reading). As an independent student, it’s important to study the right thing at the right time, something I’ve talked more about here: Time quality: Studying the right thing at the right time.

All time counts, not just time spent in a classroom – While Nation’s article is addressing language teachers, he doesn’t say that each lesson should be balanced in terms of the four strands, or not even that classroom time in general should be. Naturally, some activities are better performed outside the classroom, such as meaning-focused input or fluency development (especially for listening and reading). As an independent student, it’s important to study the right thing at the right time, something I’ve talked more about here: Time quality: Studying the right thing at the right time. Meaning-focused input takes time to have effect – According to Nation’s model, explicit vocabulary learning belongs among the language-focused activities, so this would include studying characters, using flashcards and otherwise maintaining and expanding your vocabulary. Some people, notably those focusing on comprehensible input, argue that these things are better done through more meaning-focused input. Research shows that this is clearly possible, but if you don’t focus on vocabulary, you need to see and hear words many more times for them to stick. Thus, don’t think that spending ten minutes with a podcast or graded reader will magically expand your vocabulary; you need much more than that and should expect results to come over time, not over night.

Meaning-focused input takes time to have effect – According to Nation’s model, explicit vocabulary learning belongs among the language-focused activities, so this would include studying characters, using flashcards and otherwise maintaining and expanding your vocabulary. Some people, notably those focusing on comprehensible input, argue that these things are better done through more meaning-focused input. Research shows that this is clearly possible, but if you don’t focus on vocabulary, you need to see and hear words many more times for them to stick. Thus, don’t think that spending ten minutes with a podcast or graded reader will magically expand your vocabulary; you need much more than that and should expect results to come over time, not over night.- Upgrade the way you study or teach one step at a time – Assuming that you think this article and the four strands make sense, you shouldn’t feel that you have to completely change the way you learn overnight. I think most people who read this will realise that they spend much more than 25% on language-learning activities and much less than 50% on meaning-focused activities. If this is true for you, start by removing one language-focused activity you don’t like that much and replace it with one focused on meaning. Maybe spend an hour less on reading about Chinese grammar and use that on a graded reader or podcast you like.

Let’s have a closer look at each strand to see what defines it and also what some implications are for Chinese learners.

Meaning-focused input

In order for something to qualify as meaning-focused input, it needs to fulfil certain criteria:

- Is most of what you hear or see already familiar to you?

- Are you interested in what the text or audio says?

- Is the new language you encounter restricted to a few percent of the total?

- Can you figure out the meaning of unknown language by context?

- Are you listening and reading a lot?

Only if the answer is “yes” to all five questions does it count as meaning-focused input. This is a high bar to clear, and this type of learning is almost unheard of in institutional courses for learning Chinese. Most textbooks contain much more new vocabulary than a few percent; that’s what graded readers aim for, providing you already know the words they assume you know in advance (which is rarely the case in practice). If you read something and you only encounter something you’re not sure if in every other sentence, you’re probably in the right territory. This is extensive reading and listening.

The point here is that in order to learn a language, you need to have heard and seen target vocabulary and grammatical structures many, many times in different contexts before you’ll be able to use them proficiently yourself. Most teachers and students do the opposite and focus on a very limited amount of text and audio. Progress will be slow because the content is difficult.

Standard textbooks are constructed in a way that disqualifies them as meaning-focused input, because the whole point is to teach vocabulary and grammar. While this differs from textbook to textbook, unfamiliar language is typically crammed into a very small space, often with several unknown words or grammar patterns in each sentence. This is impossible to understand without the support of word lists or other forms of guidance.

I have discussed the topic of textbooks in another article, where I discuss how they can be valuable resources for listening and reading, even with the problems discussed above: Why you should use more than one Chinese textbook.

Meaning-focused output

The next strand is meaning-focused output. Here’s how you can tell if an activity fits into this category:

- Do you talk or write about things you’re mostly familiar with?

- Is your goal to convey meaning to someone (i.e. communicate)?

- Do you already know most of the Chinese you need to accomplish this?

- Can you use communicative strategies to reach your goal?

- Are you speaking and writing a lot?

Again, it only counts as meaning-focused output if you answer “yes” to all the above questions. Some of them require further explanation, though, so let’s have a closer look at what “communication” means in this context.

One way of looking at it is to say that you’re communicating if you’re saying or writing something the recipient doesn’t already know, or if you’re trying to understand something written or spoken that you don’t already know. If I tell you that my birthday is February 27th in Chinese and you didn’t know that before, that’s communication. If you read a dialogue in your textbook where someone asks 大卫 where he’s from and he says 美国 (Měiguó), that’s not communication. If your classmate ask you what your favourite colour is even though she already knows it’s green, that’s not communication either. There needs to be an information gap between speaker and listener or between writer and reader for it to count as communication.

I also want to say a few words about strategies. Here, we’re not talking about learning strategies such as how to learn characters or how to best practise pronunciation as a beginner, but instead we’re talking about strategies you use for improving spoken or written communication. It could be something simple, like repeating yourself when you see that the other person doesn’t understand or rephrase a sentence because you forgot how to write an important character.

Strategies are of utmost importance when interacting with real people. Most of the time, meaning-focused input and meaning-focused output are combined into one activity: having a conversation, either verbally or by writing text messages of some kind. To make communication work, you need to build an arsenal of strategies you can use to ask for clarification when you don’t understand, clarify yourself when the other person doesn’t understand, and otherwise deal with problems that hinder communication to take place. For the language teachers out there, this is part of what’s called “the negotiation of meaning”.

The reason it’s important to speak and write a lot when learning a language is because these are skills that are built over time with lots of practice. Naturally, you need input first to have an idea of what works in Chinese, but nobody becomes an expert in using limited language to convey meaning without practising. Output also opens the possibility to receive feedback of various kinds, something I’ve covered in more detail here: How to get honest feedback to boost your Chinese speaking and writing.

Language-focused learning

I’m not going to spend too much time on language-focused learning, because this is what most students and teachers do all day every day. As I’ve said above, some courses at universities and language schools do almost nothing except language-focused learning. Still, I’m of the opinion that language-focused learning can be very beneficial in small doses, but that most students of Chinese are overdosing on these activities, with the result that people can study for years and still not learn much. I have talked more about this here: Learn Chinese implicitly through exposure with a seasoning of explicit instruction.

Learn Chinese implicitly through exposure with a seasoning of explicit instruction

Fluency development

The fourth and final strand, fluency development, should include all four skills (listening, speaking, reading and writing), and is about getting better at what you already know. Here’s how to tell if an activity is developing fluency or not:

- Is everything or almost everything you hear, say, read or write already known to you?

- Are you trying to receive or convey meaning?

- Is there pressure or encouragement to do so faster than you normally do?

- Are you doing a lot of listening, speaking, reading and writing?

One of the few things I don’t fully agree with in Nation’s article is the idea that pressure or encouragement to perform quickly is necessary for something to count as fluency development. I understand what he means and I sometimes do this in my own teaching as well.

An example would be to ask a pair of students to give their own answers to ten questions about their opinions on different topics within fifteen minutes, then mix up the pairs and ask them to go through the same questions in twelve minutes, then nine, and so on. Practise makes perfect, so what took fifteen minutes can be accomplished in much less time after a few tries. This is still communication, assuming that the students don’t know how the other will answer the questions.

Still, I think this doesn’t have to be explicit, and I rarely think about fluency development in these terms. If you re-listen to a podcast you studied a few months ago or listen to a new one a bit below your actual level, this surely counts as fluency development even if you don’t increase the speed of the podcast. The same is true if you read a book containing almost entirely words you already know: few people will read slowly even if they are neither pressured nor encouraged to increase speed. I agree that deliberately trying to go faster than you are comfortable with can sometimes be a good idea, but I don’t think that should be a requirement.

I’ve written a lot about fluency development, but here are two articles I think are particularly relevant: Chinese listening strategies: Improving listening speed and How to improve fluency in Chinese by playing word games. I have also written about this particular strand here: How to become fluent in Chinese:

A few final thoughts

Paul Nation is better known for his research into vocabulary acquisition, something I’ve been interested in for a long time. Thus, I only read his article about the four strands in 2015 when I started working with professional development for language teachers. Since then, I’ve had plenty of opportunity to use the model and it holds up surprisingly well. This is partly because I think I share many basic views on second-language acquisition with the author, but it’s also because the model is useful even if you don’t agree with the weighting of the strands, as I’ve already mentioned. Thus, even though the model was developed for language teachers and curriculum designers, it works well for individual independent students as well!

References

Nation, P. (2007). The four strands. International Journal of Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 1(1), 2-13.

Image source: Stilfehler, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons.

Tips and tricks for how to learn Chinese directly in your inbox

I've been learning and teaching Chinese for more than a decade. My goal is to help you find a way of learning that works for you. Sign up to my newsletter for a 7-day crash course in how to learn, as well as weekly ideas for how to improve your learning!