One of the most common analogies used to talk about learning is that it’s like moving in space. You are at point A now, you want to get to point B, and so you must find a way to move from one to the other. You move forward, you run into obstacles in your path, you work your way around them, you get closer to your destination.

One of the most common analogies used to talk about learning is that it’s like moving in space. You are at point A now, you want to get to point B, and so you must find a way to move from one to the other. You move forward, you run into obstacles in your path, you work your way around them, you get closer to your destination.

Overall, this is a good metaphor for learning Chinese, but the details matter! Learning Chinese is more like walking a thousand miles than running 100-metre dash and treating it as if it were a competition of who can run across the home straight fastest when there is in fact no competition involved and the distance you need to travel is more like a thousand miles, has consequences.

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Overcast, Spotify, YouTube and many other platforms!

There are several differences between a thousand-mile journey and 100-metre dash:

- Scale is different by several orders of magnitude, so strategies that will work well for travelling short distances often don’t work for long distances. This is true for both walking/running and learning Chinese.

- The path to your goals is never a straight line on flat ground. Indeed, sometimes even finding a path is hard! We don’t start in the same place and don’t head towards the same destination either, and most people change their goal many times.

- Learning Chinese is not a race against other learners, so there are no official rules and no prize waiting for you at a finish line. Most importantly, someone else getting a burst of speed and overtaking you is not bad.

Let’s have a look at these in more detail and what they mean for you as a learner of Chinese.

The road to mastering Chinese is long

While the numbers I’ve given so far are arbitrary, it’s important to understand that learning Chinese takes time. If you invest all the time you have, you might be able to make great progress in a few months or a year, but if your goal is to reach an advanced level of Chinese, it’s going to take much longer than that. If you study part time, it’s going to take even longer.

This means that you need to evaluate learning strategies and activities both from a short-term and a long-term perspective. They need to work not just to achieve the goals you have for learning this week, they need to be sustainable in the long term.

Here are some observations using the same analogy as before:

Exactly how you start doesn’t matter, the point is that you’re moving. In 100-metre dash, the start is extremely important, but if you are going to walk a thousand miles, you don’t care about saving a sliver of time when you set out. When learning Chinese, don’t obsess over finding the right method for learning straight away (you won’t) and don’t worry about getting things wrong (you will anyway, but you can fix that later). Just get moving and keep moving. Read more here: Analysis paralysis: When choosing method becomes a problem.

Exactly how you start doesn’t matter, the point is that you’re moving. In 100-metre dash, the start is extremely important, but if you are going to walk a thousand miles, you don’t care about saving a sliver of time when you set out. When learning Chinese, don’t obsess over finding the right method for learning straight away (you won’t) and don’t worry about getting things wrong (you will anyway, but you can fix that later). Just get moving and keep moving. Read more here: Analysis paralysis: When choosing method becomes a problem.

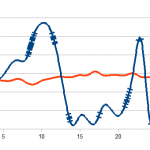

Your average pace matters, not your top speed. When running 100 metres, a sprinter keeps accelerating almost the entire race. The top speed you reach is extremely important because you can keep it to the finish line, and it will determine your time. When walking a thousand miles, however, sprinting 100 metres in 10 seconds is bad if you want to travel a thousand miles, because it’s a wasteful use of energy. A human can easily outrun a cheetah over long distances. I’ve written more about this here: Your slumps affect your language learning more than your flows.

Your average pace matters, not your top speed. When running 100 metres, a sprinter keeps accelerating almost the entire race. The top speed you reach is extremely important because you can keep it to the finish line, and it will determine your time. When walking a thousand miles, however, sprinting 100 metres in 10 seconds is bad if you want to travel a thousand miles, because it’s a wasteful use of energy. A human can easily outrun a cheetah over long distances. I’ve written more about this here: Your slumps affect your language learning more than your flows.

Motivation is more important the farther you need to go. If you’re fit, running 100 metres as fast as you can requires only a basic motivation to try it. I run a lot, and when I try to run 10 kilometres as fast as I can, it does require motivation to not give up after about half the distance, but I can just push through. When you walk a thousand miles, though, motivation is everything. If you don’t have a good reason to keep walking, you will stop at some point, distracted by all the pretty things scattered along the road. I’ve mused about this and related topics here: Enjoying the journey while focusing on the destination.

Motivation is more important the farther you need to go. If you’re fit, running 100 metres as fast as you can requires only a basic motivation to try it. I run a lot, and when I try to run 10 kilometres as fast as I can, it does require motivation to not give up after about half the distance, but I can just push through. When you walk a thousand miles, though, motivation is everything. If you don’t have a good reason to keep walking, you will stop at some point, distracted by all the pretty things scattered along the road. I’ve mused about this and related topics here: Enjoying the journey while focusing on the destination.

Many people, especially those who aren’t learning Chinese or have only been learning it for a while, misunderstand the real challenge. Chinese is difficult to learn, not because each step is hard but because there are so many steps. And as I argued in a recent article, you should think twice before forcing yourself to use methods you don’t enjoy:

Should you use an efficient method for learning Chinese even if you hate it?

The winding road to Chinese fluency

Learning Chines is not like any kind of organised sports event except orienteering. Regardless of if you run 100-metre dash or an ultramarathon, the start, the end and the path between them are usually set for you. When you learn Chinese, you get to choose both the destination and how to get there. There might be some things that look like a trail, but these might not lead you where you want to go and should be used cautiously. A good example of this is HSK, which you shouldn’t use as a roadmap for learning Chinese.

Instead, exploring the landscape and finding a way forward is part of what it means to be an independent language learner. This can sometimes be frustrating, but there really is no other sensible option. You’re the one learning the language, you should be in control.

Identify the goal, then plot how to get there

The solution is two-fold: First, you need to figure out where you want to go. This could be something you already know, but many students aren’t clear about why they’re learning Chinese. Being aware of where you want to go is important because it helps you determine what skills you need to pick up; it helps you plot the path ahead, in other words. Read more about why goals matter here: Why you need goals to learn Chinese efficiently

Second, you need to find a path from where you are now to where you want to be. This is trickier and there are no one-size-fits-all solutions, as it depends on what situation you’re in, what your specific challenge is and much more.

Hacking Chinese is in a sense an attempt to provide hundreds of different answers to this question, so if you want to read about how to improve in a specific area, check the sidebar (desktop) or footer (mobile) and click the category you’re interested in. You’ll get to a page summarising that area of learning Chinese, followed by articles in that category.

Goal setting and plotting a path from where you are to where you want to be is also covered in my course Hacking Chinese: A Practical Guide to Learning Mandarin. If you’re interested in that, you can read more here:

Learning Chinese is not a competition

Even though friendly competition can provide a form of motivation, such as in the shape of Hacking Chinese Challenges, learning Chinese is not a race. While I don’t think that most readers of this article think that it is, this still is common in discussion fora and on social media. If you don’t reach a certain milestone in a certain time, you’re a bad learner. Look at me, I passed HSK5 in a year! And so on.

The most destructive version of regarding Chinese as a race is when you envy other students for doing better than you, or even think that they are performing worse is somehow good for you. This is clearly nonsense, but an attitude I have encountered many times. Why share notes from yesterday’s lesson if it can give you an advantage over your classmates?

If you are going to compete, compete against yourself

If I were to identify one of the most significant strengths I have in life, it would be that I really don’t care about competing with other people. I do care about learning, improving and achievements, but I don’t view these things in the light of what other people do; I only compare with myself.

A slightly more fruitful way of regarding learning Chinese as a competition is to see who can improve efficiency the most, meaning how much you get out of each unit of time you invest in learning. This is not very glamorous, though, but it is equally important for those who study full time and those who study a few hours a week.

Still, I have yet to meet a student with a long-term goal that involves comparing with another student. Learning Chinese to outshine your brother or to show your classmate that you’re smarter than she is, might work for short-term learning in middle school, but it would be bizarre as long-term goal for an adult learner.

That means that the only competition you should engage in seriously is with yourself. Try out that mimic method you’ve heard about for learning pronunciation, and see if you can listen a bit more this month’s listening challenge compared to last month or the previous challenge if you participated in it. The goal is to keep moving and improve relative to your past self, not somebody else.

Also, don’t forget that since you’re not competing with other learners, enlisting them for help is great advice! Running with other people is easier and you can lean on other people’s motivation when yours is flagging. Cycling in a group creates a favourable slipstream that is beneficial for all in the group. You shouldn’t walk the road to Chinese fluency alone.

Learning Chinese is more walking a thousand miles than running 100-metre dash

In this article, I have argued that which analogies we use to think about language learning matters. To be more precise, the 100-metre dash analogy is detrimental and should be replaced with a thousand-mile journey into an unknown and exotic land. This requires a different mindset and different strategies.

Good analogies can be useful, because they allow us to investigate a question from new angles, coming to new insights as we do so. I have merely scratched the surface of the language learning is a journey metaphor here and might have missed some key observations. If so, please leave a comment below!

And don’t forget: 千里之行始于足下 (qiān lǐ zhī xíng shǐ yú zú xià), “even a thousand-mile journey starts with a single step”!