In last week’s article, we saw that learning Chinese characters is not enough, you also have to learn words. Most words contain two characters, or two syllables in the spoken language, but there are words with only one character or with three or more characters as well.

In order to understand and remember compound words, and also to be able to use many of them properly, you need to pay attention to the internal structure of the words and what the individual characters mean.

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to this article:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcast, Overcast, Spotify and many more!

In this article, we’re going to take a closer look at compound words with the goal of making them easier to learn, but before we do that, let’s have a look at the other articles in this series:

- Part 1: Chinese characters in a nutshell

- Part 2: Basic characters and character components

- Part 3: Compound characters

- Part 4: Learning and remembering compound characters

- Part 5: Making sense of Chinese words

- Part 6: Learning and remembering compound words

Learning and remembering compound words

There are many different types of compound words in Chinese, and there is in fact a whole area of study called “morphology” that deals with words, word forms and word formation. The goal here is not to help you write a term paper in Chinese linguistics, however, but to help you learn Chinese effectively and efficiently. That means that what I say here is simplified and that there’s much more to Chinese morphology than it’s possible or even desirable to present in this article.

If you’re looking for a relatively accessible overview, I recommend Sun Chaofen’s Chinese: A linguistic introduction (2007). If you want a closer look at morphology (still in English), check Jerome Packard’s The Morphology of Chinese: A Linguistic and Cognitive Approach (2000). Links go to Amazon.

If you want the essential things you really have to know and that will have an immediate impact on your ability to learn and remember words, keep reading this article instead!

Like I said above, most Chinese words consist of two characters. They are therefore compounds, but a different kind of compounds compared to what we have looked at earlier in this series. We have seen how character components fit together to form characters, and that knowing more about how they do so can help immensely with learning characters.

Let’s do the same thing with compound words!

Morphemes are the smallest meaningful units

First, we need to talk about what a “morpheme” is. A morpheme is the smallest meaningful lexical (vocabulary-related) unit. Let’s use English as an example before we move on to Chinese. A morpheme is not the same as a word, because words can contain several morphemes. For example, the word “hunters” contains three morphemes:

- Hunt, the root of the word

- -er, signifying a person; someone who engages in the hunt

- -s, showing that there is more than one such person (plural)

So one word, three morphemes. However, you can see that the two latter ones are not like the first. The first one can be freely used on its own, and is called a “free morpheme”. The others are bound together with other morphemes and can’t be used on their own, and are therefore called “bound morphemes”.Of course, words can contain more than one free morpheme as well, such as “blackbird”, “wheelchair” and “football”.

Now that that’s out of the way, let’s see how this works in Chinese. In Mandarin, we also have free and bound morphemes. Many characters can be used on their own, but not as many as in Classical Chinese where characters and words often are the same thing.

Some of the compounds we looked at in the previous article are composed of two free morphemes. All the characters here can be used independently to form new sentences.

- 大家 (dàjiā) “everybody”

- 你好 (nǐhǎo) “hello”

- 吃饭 (chīfàn) “to eat”

Bound morphemes can only form words together with other morphemes

Not all words we looked at are like that, however, and at least one component character can’t be used on its own. Here are three more examples:

- 大衣 (dàyī) “overcoat”

- 足球 (zúqiú) = “football“

- 睡觉 (shuìjiào) “to sleep”

In the first example, 大 can of course be used on its own, but 衣 can’t. Still, knowing that 衣 itself means “clothes” is very useful, because it brings that meaning to many compound words, such as 衣服 (yīfu) “clothes”, 睡衣 (shuìyī) “pyjamas” and 洗衣 (xǐyī) “laundry”.

In the second example, 球 can be used on its own to mean “ball”, although exactly how free it is depends on if the word is supposed to mean “football” (the sport) or “football” (the round object you use to play the game). 足 is slightly trickier, because the most common independent usage Mandarin is probably when it means “enough”, as in 不足 (bù zú) “not enough” or 很足 (hěn zú) “plenty”. It can be used to mean “foot”, but it sounds rather technical as in an anatomy textbook. In everyday language, you should use 脚 (jiǎo) for “foot” instead.

In the third example, 睡 can be used as a verb on its own, which is extremely common, so no discussion there. 觉 on the other hand seems to only appear as the object of 睡 as we saw in the previous article. This can mean that other words get inserted between the verb and the object, as in 睡不了睡 (shuì bu liǎo jiào) “to be unable to sleep”.

Then we also have words where no component can be used on its own, such as 玻璃 (bōii) “glass”, 蝴蝶 (húdié) “butterfly” and 蘑菇 (mógu) “mushroom”, but these are less common than the others.

Four different types of compound words in Mandarin

This gives us four ways of combining free and bound morphemes for two-syllable words:

- Free + free (e.g. 吃饭)

- Free + bound (e.g. 睡觉)

- Bound + free (e.g. 足球*)

- Bound + bound (e.g. 玻璃)

*At least in everyday usage, see above.

We’re now going to look at each of these categories in more detail, although the goal here is to show principles and give examples, not to provide exhaustive lists. Put briefly, you can think of the categories this way:

- Free + free = combinations of parts that are in themselves words

- Free + bound = a word followed by a suffix

- Bound + free = a word with a prefix in front of it

- Bound + bound = two characters that only form a word when combined

1. Free + free = combinations of parts that are in themselves words

Chinese words are structured the same way as Chinese phrases

In the first category, where each part of a compound also is also a word in itself, is fairly straightforward, because the meaning of the characters involved are often readily available in normal dictionaries. There’s also a chance that you will have learnt them as independent words before you encounter them in a compound, which means that you only need to learn the extra meaning they have when combined.

From a memory perspective, this is also an easy category because the words here easily lend themselves to mnemonics. It’s not hard to come up with concrete images for words that are used on their own, or it’s at least easier than doing it for characters that have no independent meaning or have purely grammatical functions. I wrote more about how to combine concrete images for easy memorisation here:

Still, understanding the structure of the compound can make it easier to remember, and even more importantly, it can make it easier to remember the order the components are supposed to go in. Students mix up the order of characters within words often, probably because they don’t really understand the structure! Mor about this alter.

In compound nouns, the core noun is on the right

In general, nouns have the core noun component on the right, and verbs have the core verb component on the left. This is true in around 90% of cases. See Packard (2000) and Huang (1997) for a more detailed overview of the data.

If you think about it, this mirrors how Chinese grammar works too.

We have looked at some nouns, such as 足球 (zúqiú), 大衣 (dàyī) and 商店 (shāngdiàn), and here we can see that the core noun is on the right and the thing describing or delimiting its meaning is on the left.

足球 refers to a ball. What ball? A football.大衣 refers to clothes and 商店 is a store. This is the same as ordinary grammar where you have phrases like 我的球 (wǒ de qiú) or 红色的大衣 (hóngsè de dàyī) or 那边的商店 (nàbian de shāngdiàn).

In compound verbs, the core verb is on the left

On the other hand, if you have a verb, its object follows on the right, not the left. Following standard word order, you say 吃午饭 (chī wǔfàn), where the verb is clearly on the left of the object, not *午饭吃. We also looked 跳舞 (tiàowǔ), 睡觉 (shuìjiào) and 关心 (guānxīn) in the previous article and they all have the a verb on the left.

This is extremely useful for figuring out what order the components are supposed to be in.

How the meaning of components are related within Mandarin nouns

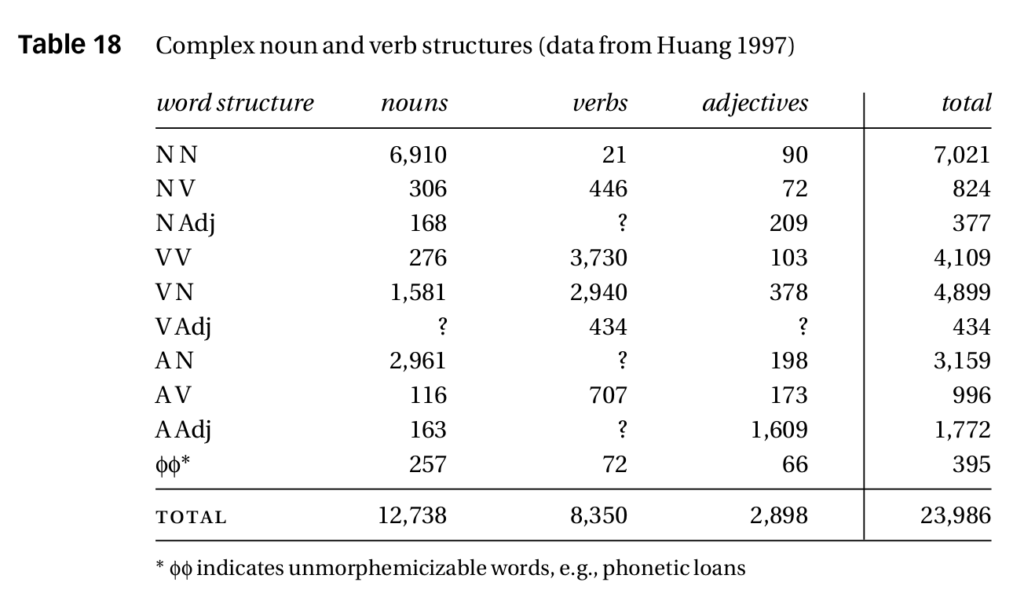

Packard (2000) lists a large number of types of relationships between both noun and verb formants within words. He also notes that most of the nouns are combinations of two nouns (54%) and that most verbs are combinations of two verbs (45%). He includes this table with data from Huang (1997). If you check the column with nouns, note that most of them are noun + noun compounds (and almost all the rest are other compounds with the noun on the right, as explained earlier).

Let’s look at the ways in which the components of nouns relate to each other, not in terms of structure (they are all nouns, after all) but when it comes to meaning. Below, N₁ means the first noun, and N₂ means the second noun.

N₁ is the place where N₂ operates or is located:

N₁ is the place where N₂ operates or is located:

- 眼镜 (yǎnjìng) eye + lens = “glasses”

- 手表 (shǒubiǎo) hand + watch = “wristwatch”

N₂ indicates a medical condition of N₁:

- 肺炎 (fèiyán) lung + inflammation = “pneumonia”

- 胃癌 (wèiái) stomach + cancel = “stomach cancer”

N₁ depicts the form of N₂:

- 砂糖 (shātáng) sand + sugar = “granulated sugar”

- 砖茶 (zhuānchá) brick + tea = “brick tea; compressed tea”

N₂ depicts the form of N₁:

- 雪花* (xuěhuā) snow + flower = “snow flake”

- 冰块 (bīngkuài) ice + piece = “ice cube”

*Packard notes that this should be parsed as “a flower (shaped thing) made of snow)”, so it doesn’t violate the rule that the core noun is on the right and the thing that describes it is on the left, which it might look like at first, as it is after all snow, not a flower. Similarly, we don’t say “flake snow” in English either.

N₂ is used for N₁:

- 机场 (jīchǎng) machine + field = “airport”

- 球拍 (qiúpāi) ball + paddle = “racket”

N₁ is the habitat of N₂:

- 水鸟 (shuǐniǎo) water + bird = “aquatic bird”

- 松鼠 (sōngshǔ) pine + rat = “squirrel”

N₂ is caused by N₁:

- 水灾 (shuǐzāi) water + disaster = “flood”

- 车祸 (chēhuò) vehicle + misfortune = “vehicle accident”

N₂ is a container for N₁:

- 茶杯 (chábēi) tea + cup = “teacup”

- 书包 (shūbāo) book + bag = “schoolbag”

N₂ is produced by N₁:

- 鸡蛋 (jīdàn) chicken + egg = “(chicken) egg”

- 牛奶 (niúnǎi) cow + milk = “(cow’s) milk”

N₂ is made from or composed of N₁:

- 铁路 (tiělù) iron + road = “railroad”

- 猪肉 (zhūròu) pig + meat = “pork”

N₁ is a type or subclass of N₂:

- 兰花 (lánhuā) orchid + flower = “orchid”

- 苹果 (píngguǒ) apple + fruit = “apple”

N₁ is a metaphorical description of N₂:

- 银行 (yínháng) silver + business = “bank”

- 火车 (huǒchē) fire + vehicle = “train”

N₂ is a source of N₁:

- 电池 (diànchí) electricity + pool = “battery”

- 油井 (yóujǐng) oil + well = “oil well”

N₁ is a source of N₂:

- 海盐 (hǎiyán) sea + salt = “sea salt”

- 花粉 (huāfěn) flower + powder = “pollen”

N₂ is something that N₁ has or contains:

- 手掌 (shǒuzhǎng) hand + palm = “palm”

- 房顶 (fángdǐng) house + top = “roof”

N₁ is something that N₂ has or contains:

- 名片 (míngpiàn) name + strip = “name card”

- 厕所 (cèsuǒ) toilet + place = “toilet”

There are also many nouns that have two noun components that both mean the same thing and there is no obvious hierarchy between them. For example:

- 墙壁 (qiángbì) wall + wall = “wall”

- 森林 (sēnlín) forest + forest = “forest”

- 眼睛 (yǎnjing) eye + eye = “eye”

There are also cases where both components are members of a class of objects, and by putting them together in a word, the whole category is indicated. For example:

- 山水 (shānshuǐ) mountain + water = “scenery”

- 图画 (túhuà) chart + picture = “picture”

- 灯火 (dēnghuǒ) light + fire = “lights”

How the meaning of components are related within Mandarin verbs

Let’s turn to verbs! As stated above, 45% of verbs are composed of two verb components. You can check the table included above for details, but to summarise, almost all verbs have a verb component on the left and most of these also have a verb component on the right, but some also have a noun component on the right. Packard (2000) describes three different kinds of verb compounds:

- Verb + verb compounds

- Resultative verbs

- Verb + object compounds

Verb + verb compounds

Let’s have a quick look at some examples!

Verbs where both components mean the same thing:

- 讨论 (tǎolùn) discuss + discuss = “to discuss”

- 阅读 (yuèdú) read + read = “to read”

- 指导 (zhǐdǎo) point (out) + guide = to direct; to guide”

Verbs where each component refers to a distinct activity and the overall meaning is not a category where both belong:

- 观察 (guānchá) observe + investigate = “to investigate”

- 叫醒 (jiàoxǐng) call + wake up = “awaken by calling”

- 追求 (zhuīqiú) pursue + seek = “seek and pursue”

There are also some verbs which work a bit like the nouns we have discussed, i.e. where the first verb specifies the second:

- 飞行 (fēixíng) fly + go = “to fly”

- 喊叫 (hǎnjiào) shout + call = “to shout”

- 仿造 (fǎngzào) imitate + make = “to make an imitation”

Resultative verbs

These are words formed by taking a verb and adding a resultative complement to it. Here are a few examples from different categories:

- Stative resultatives: 吃饱 (chībǎo), 吃得饱 , 吃不饱

- Directional resultatives: 跑上* (pǎoshang), 跑得上, 跑不上

- Attainment resultatives: 看到 (kàndao), 看得到, 看不到

*Usually with something after it, so 跑上楼 etc..

However, I think this is closer to grammar and syntax, so I will save a deeper discussion of how this works for some other time.

Verb-object compounds

This is a category of words that is very interesting, but mostly for linguists because it’s a good example of a tricky problem. We already discussed this in the previous article, so I refer to that if you want to know what all the fuss is about. Packard (2000) of course has an overview of the debate and also a proposed solution, but it has little practical value for individual students, because most of the debate is about where to draw the line between a word and a phrase. As we saw in the previous article, this matters, but not much if the goal is to learn and remember words, which is our goal here.

Reversible words in Mandarin and how to deal with them

You should know by now that the key to getting the order right is to understand the components and the structure of words in general, which often will tell you the particular word you’re interested in. With this knowledge at hand, it’s very easy to sort out words where the order is reversible, i.e. where both versions exist.

Let’s look at a few examples:

- 牙刷 (yáshuā) “tooth brush” vs. 刷牙 (shuāyá) “to brush teeth” – This should never cause any trouble, provided that you know the components. 牙刷 is a noun and we know that the core noun component is usually on the right, so it’s a brush, not a tooth. What brush? A tooth brush. Same as in English. 刷牙 is a verb and we know that the core verb component is on the left, so to brush, not some other verb related to teeth. Brush what? Your teeth. Same as in English again.

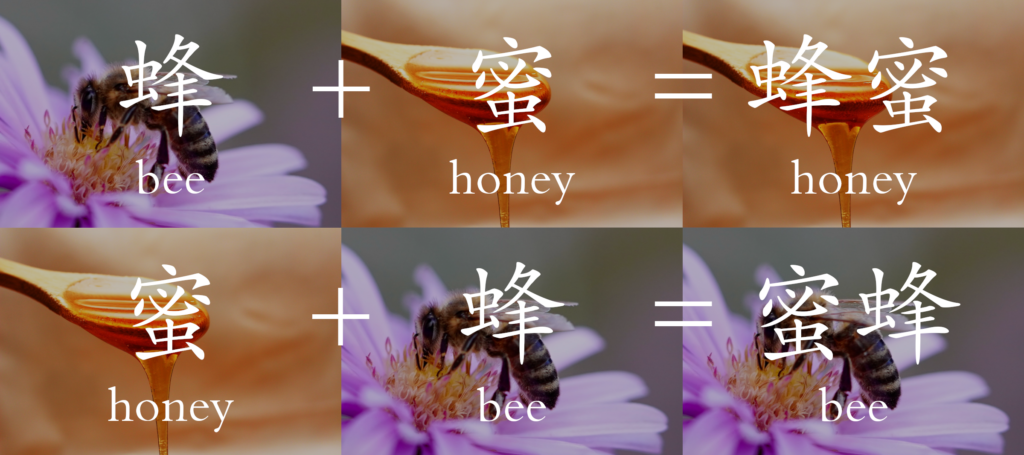

- 蜂蜜 (fēngmì) “honey” vs. 蜜蜂 (mìfēng) “bee” – Both these are nouns, so they should be very easy to keep separate if you know the components. It also happens to be the same in English: “bee honey” vs. “honey bee”. The former is something you can eat and the latter is a flying insect.

- 法语 (fǎyǔ) “French” vs. 语法 (yǔfǎ) “grammar” – In this case, you can’t look at compound words in English, but with some understanding of the words here ,it’s still easy to remember which one is which. 语 is a common suffix for languages (英语, 汉语, 日语 etc.) so what kind of 语 are we talking about? 法语! 法 doesn’t mean “law” here, of course, but is a phonetic loan. In the other case, 法 does mean “law”, though, what law? The laws that govern language, so 语法, or “grammar”.

This doesn’t mean that all cases will be easy, and as I have said before and will say again, languages are sometimes rather arbitrary, and rules can only take us so far:

- 地道 (dìdao) vs. 道地 (dàodì) – Both these words can mean the same thing, i.e. “authentic; original”. Which is used is a regional difference, so on the mainland, people tend to use 地道 and in Taiwan, people use 道地. Is there any way to predict this? No.

- 适合 (shìhé) vs. 合适 (héshì) – Both these are related to something being suitable, but they differ in how they are used. 合适 is mostly used as an adjective, so you can say 这件衣服很合适 (zhè jiàn yīfu hěn héshì) “this piece of clothing is suitable”, but 适合 is used as a verb, so: 这件衣服适合你 (zhè jiàn yīfu shìhé nǐ) “this piece of clothing suits you”. And can you know that by analysing the component characters? I don’t think so.

- 积累 (jīlěi) vs. 累积 (lěijī) – Both verbs mean the same thing: “to accumulate” and are largely interchangeable, but have a slightly different feel, where 累计 is something you might realise have accumulated over time, whereas 积累 is more actively accumulating something. In the sentence 这几年,我__很多工作经验 (zhè jǐ nián, wǒ ____ hěn duō gōngzuò jīngyàn), buth words work, but with 累计, you’re maybe reflecting on what you’ve done in the past few years, whereas with 积累, accumulating all that experience was something you deliberately did. Again, this is not something you can figure out by looking at the words.

For these cases, vast amounts of exposure with a seasoning of explicit learning is probably the best approach:

Learn Chinese implicitly through exposure with a seasoning of explicit instruction

2. Free morpheme + bound morpheme = a root word followed by a suffix

That was a rather long discussion of the semantic (meaning) relationships between the components within compound nouns and verbs, but it’s time to move on and have a look at a the second type of word structure, namely where we have a free morpheme followed by a bound morpheme, which acts like a suffix. As before, the goal here is to explain principles and give examples, not exhaustively list all suffixes.

Please note that this type of word is not generally predictable, i.e. you can’t know when you can and cannot add a suffix to a certain root. Thus, this is a way to understand words you encounter, not guess how to say something you don’t know how to say. The categories are from Sun (2007), but I’ve chosen more suitable (easier) examples in many cases.

子 (zi) indicating a noun, original a free morpheme meaning “child” (zǐ)

- 桌子 (zhuōzi) “table”

- 鼻子 (bízi) “nose”

- 房子 (fángzi) “house”

学 (xué) meaning “study”, indicating a school or discipline

- 数学 (shùxué) “mathematics”

- 化学 (huàxué) “chemistry” (i.e. the study of change or transformation)

- 小学 (xiǎoxué) “elementary school”

度 (dù) “degree”, or how much there is of something, turning it into a noun

- 速度 (sùdù) “speed” (i.e. “degree of fast”)

- 难度 (nándù) “difficulty (i.e. “degree of difficulty”)

- 透明度 (tòumíngdù) “transparency” (i.e. “degree of transparent”)

化 (huà) “change”, turning something into a noun denoting change

- 老化 (lǎohuà) “aging”

- 现代化 (xiàndàihuà) “modernisation”

- 内化 (nèihuà) “internalisation”

头 (tou), which normally means “head”, but is also used for nouns in a similar way to 子

- 木头 (mùtou) “wood”

- 舌头 (shétou) “tongue”

- 老头 (lǎotóu) “old man”

员 (yuán), indicating a person or a member of a group, also turning the word into a noun

- 运动员 (yùndòngyuán) “athlete” (i.e. “sport-person”)

- 服务员 (fúwùyuán) “waiter” (i.e. “service-person”)

- 店员 (diànyuán) “shop assistant” (i.e. “shop-person”)

This is maybe a good opportunity to bring up the complexity of suffixes and the arbitrariness of languages. Here are a few more similar suffixes that can be used in a similar way:

- 家 (jiā), e.g. 作家 (zuòjiā) “author”

- 者 (zhě), e.g. 记者 (jìzhě) “journalist”

- 生 (shēng), e.g. 学生 (xuésheng) “student”

- 师 (shī), e.g. 律师 (lǜshī) “lawyer”

- 人 (rén), eg. 军人 (jūnrén) “soldier”

While there are some patterns here, there are no hard rules, so you can’t predict what a certain word will look like. An example of a pattern might be that 师 refers to a master and 生 to a student, but why is it 医生 (yīshēng) and 厨师 (chúshī) for “doctor” and “cook”, then? What makes one a master but not the other? If you want more examples of each, this blog post lists quite a lot of them.

There’s also suffixes that work almost like inflections in English, such as:

们 (men) indicating plural or a collective (usually of people)

- 我们 (wǒmen) “we”

- 他们 (tāmen) “they”

- 孩子们 (háizimen) “the children”

But most of them are out of scope for this article and belong in a bigger discussion about grammar, such as…

- 了

- 过

- 着

…and so on.

3. Bound morpheme + free morpheme = a root with a prefix in front of it

We can of course also have the reverse of the above, so the free morpheme on the right and then a prefix on the left. Here are some examples to show you how it works:

小 (xiǎo) “small” and 老 (lǎo) “old”, used to indicate familiarity

- 小林 (Xiǎo Lín), “small Lín”, normally used when someone is younger than you

- 老张 (Lǎo Zhāng), “old Zhāng” normally used when someone is older than you

老 (lǎo) “old” can also be used in animal names, but has nothing to do with familiarity

- 老虎 (lǎohǔ) “tiger”

- 老鼠 (lǎoshǔ) “rat”

小 (xiǎo) “small” can of course also mean small in a more literal sense

- 小菜 (xiǎocài) “dish”

- 小孩 (xiǎohái) “child”

Other prefixes include 第 (dì) indicating ordinal numbers, e.g. 第一 (dì yī) “first”, and 初 (chū) indicating “beginning”, e.g. 初稿 (chūgǎo) “first draft”.

4. Two bound morphemes = two characters that only form a word when combined

This category is much smaller than the others and contains words whose component parts can’t be used on their own. We already looked at 玻璃 (bōli) “glass” before, where neither 玻 nor 璃 can be used independently. There are also many animals and plants that have names of this type, such as 蝴蝶 (húdié) “butterfly” and 蘑菇 (mógu) “mushroom”. It’s not restricted to these types of words, though, and a common example of a verb is 讨论 (tǎolùn).

You can also count sound loans from other languages into this category if you want, because while 巧克力 (qiǎokèlì) does mean “chocolate” and 咖啡 (kāfēi) means “coffee”, there’s no internal logic in these words; the characters merely represent sounds in a foreign language.

From a learner perspective, you don’t really need to treat words in this category differently from the free + free compounds we have already discussed. When memorising these words, it doesn’t really matter that they happen to be bound morphemes in modern Mandarin, you can still treat them as meaningful units and create mnemonics accordingly.

However, the order is often arbitrary, so you can’t use the rules we’ve talked about earlier to remember what character goes first. I think the solution here is simply to use the language more, including the spoken language. You won’t say *菇蘑 (gūmó) or *蝶蝴 (diéhú) if you’ve actually used these words and seen or heard them in context many times.

Chinese characters that share the same components but are still different

Conclusion: Learning Chinese words really fast

I think it should be clear by now that Chinese words can actually be easy to learn, provided that you know the building blocks and how they fit together. We explored how to learn the building blocks in the first few parts of this series, and in this and the previous article, we discussed how they fit together to form words.

Learning words in Chinese can be very fast once you have the foundation. This is both because the words intuitively makes a lot of sense, often more so than in English (compare 肺炎 (fèiyán) and “pneumonia” for example, which is most transparent?), and because if you know the building blocks, you can unleash the full power of mnemonics.

Here’s what the process looks like (although you don’t have to do it in this order):

- Learn the building blocks (the individual characters)

- Connect them together using logic and or mnemonics

- Upgrade, reinforce and replace weak links (words you forget)

- Speed!

While this article is written in 2021, I still want to include some data from an experiment I ran almost exactly a decade ago, when I had studied Chinese for a few years. Please note that all this requires a lot of practice with mnemonics and that you really do need a solid foundation first.

So back in 2011, I conducted a small and very unscientific experiment to see how well this method works for learning vocabulary. Naturally, I’ve been using similar methods almost from the start, but I decided to test the limits. Going through the vocabulary list to an advanced level proficiency test, I found there were around 2,000 words I didn’t know.

It took me little more than three hours a day for five days to go through that list, averaging about 400 words per day, 135 words per hour or just over two words per minute. Using spaced repetition software, I was able to retain about 90% of these words, spending another ten hours over the following weeks. This doesn’t mean that I could use all these words properly, of course, but it was enough to significantly boost my reading ability.

I didn’t share this with you in order to boast, I did so because I’m convinced that it’s possible for most people to do this (or something similar) given that you have made the proper preparations. Naturally, building up an extensive knowledge of individual characters and how they fit together takes years, but I hope that this article has made it a little bit easier to make sense of words in Chinese!

References and further reading

Duanmu, S. (2007). The phonology of standard Chinese. Oxford University Press.

Huang, S. (1997). Chinese as a headless language in compounding morphology, in Packard (1997). New Approaches to Chinese Word Formation: Morphology, phonology and the lexicon in modern and ancient Chinese. Trends in Linguistics Studies and Monographs . Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Packard, J. L. (2000). The morphology of Chinese: A linguistic and cognitive approach. Cambridge University Press.

Sun, C. (2006). Chinese: A linguistic introduction. Cambridge University Press.

Zhao, J. (2006). Japanese loanwords in modern Chinese. Journal of Chinese Linguistics, 34(2), 306-327.

邵敬敏 (Ed.). (2007). 现代汉语通论. 上海教育出版社.

Editor’s note: This article, originally published in 2010, was rewritten from scratch and massively updated in December, 2021.

Tips and tricks for how to learn Chinese directly in your inbox

I've been learning and teaching Chinese for more than a decade. My goal is to help you find a way of learning that works for you. Sign up to my newsletter for a 7-day crash course in how to learn, as well as weekly ideas for how to improve your learning!

58 comments

Hi,

I’ve been enjoying reading through your brain hacking tips and tricks and would like to say thank you for writing it. While I have been using a lot of the techniques discussed, you’ve certainly made me aware of other approaches.

Reading through this article I noticed two of your links seem to be broken:

Integrate what you learn into the web of things you already know (https://www.hackingchinese.com/?p=199) and

Make sure that the associative bonds are very strong (https://www.hackingchinese.com/?p=175)

Just thought I should let you know 🙂

Thanks again! Really appreciate your work.

Thank you for pointing this out! This is an unpublished but written article, that’s why the link doesn’t work. I haven’t yet found a smart system to handle links to articles that I’ve written but that haven’t been published yet. Removing the link would probably mean less interconnectivity on the site because I cant’ keep track of a large number articles and links between them. Keeping the link means some confusion and frustration, I’ll look into other ways of handling this, thanks for your input and sorry for the inconvenience!

Just write what you just wrote there about why you have these links on the page where you’re going to write the new article,and then just replace that text when the time comes to actually write it

Yes, but assuming I do that regularly, how do I keep track of which bits of text to change once a character goes online?

WHat I do nowadays is just save a link back to the article in question in a new draft and then, when I publish that, I go through the list of links (which is usually very brief) and add links. Not terribly efficient, but still works.

Hello,

You say:

” It took me little more than three hours a day for five days to go through that [2000 word] list, averaging about 400 words per day, 135 words per hour or just over two words per minute.”

In another post (Memorising dictionaries to boost reading ability), you say:

” a couple of years ago I spent roughly one hundred hours spread out over six weeks learning all the characters in the Far East 3000 Chinese Characters Dictionary.”

The question I’d like to ask is: did you cram the 3000 characters before you crammed these 2000 words? I’d believe so, as I suppose it’s much easier to learn words formed from characters you already know (it does not diminish your achievement though – it’s still awesome). It’s the logical process you expound in the “Powerful toolkit” series. Someone who doesn’t know, say, 2000 (?) or 3000 characters (?) would find it much harder to embark in this.

Anyway, you inspired me to try to boost my reading ability by memorising at least 500-1000 characters from a frequency list – that’s why I ask.

laurenth

@laurenth: You are perfectly correct, I did the 3000 characters project in the winter of 20010 and the massive vocabulary project one year later. It wouldn’t have been harder without the characters, it would have been impossible. 🙂 I’m not sure if I’ve stressed this enough in the articles, but you have to have a solid foundation.

Of course, it’s a parallel process. I don’t advocate learning 3000 individual characters and then starting to learn words. How you divide the time between individual characters and useful words is quite difficult and I have no solid answer, I just know that you have to focus on the toolkit. The more tools you have, the easier it will become at advanced levels.

To give you another example, I’m now going through a list of idioms at a pace of roughly 100 new per day. These are all new, meaning that idioms already in my decks aren’t included. This is possible because I can either guess the meaning of the idiom based on the individual characters, or at least I can see the logic once I’ve seen the explanation once. It doesn’t work for all idioms, but still for a vast majority (above 90%). This is just another example where knowing basic stuff well is essential to learn more advanced things.

So, good luck and keep it up! If you don’t have enough characters, you can learn them on the way. Make sure you remember to add at least one example and include that in the entry for the single character (I didn’t do that in the beginning and that sucks).

Thanks for the clarification. According to my Anki deck, I’m supposed to know 1100 unique hanzis (it’s a word deck, not a character deck). My objective is to cram the next 500 hundred, drawn from Patrick Hassel Zein’s list, in 1 month (that’s in addition to my other Chinese-related activities… and the rest: I have a job, a wife and 3 kids, so I can’t devote 4 hours/day to Chinese…). *If* that works, I may try the next 500 hundred and than stop until my knowledge of words catches up with the characters.

It sounds like you have set a reasonable goal for yourself. If you’re busy with other things, make sure to diversify your learning as much as possible. Do you use a smart phone to review? Do you utilise small slots of time during the day to check some tricky words? This is essential if you’re not studying full time. It would be interesting to follow your progress, so please report again later. I think learning an additional 500 individual characters is a really good idea. It will significantly increase your ability to guess words and will make it easier to learn more. Also, you will notice a big difference between knowing 1100 and 1600. The difference between 4100 and 4600 is not that big, so it would be debatable whether that would be worth it or not, but in your case, go for it. Good luck! 🙂

Yes I do own a smart phone, which is loaded with Chinese related software (Ankidroid, Pleco, Remata, HanpingChinese, Linghao…) and files (mp3, pdf, txt…), so I can do almost anything I want whenever I have five minutes of free time: commuting, coffee break, lunch, queuing, toilets, whatever.

For what it’s worth, here is the way I’m working on this project. I have established a list of 510 characters I want to learn (more or less # 1000 – 1500 from P. Zein’s list). I split the list into 30 small csv files called 01.csv, 02.csv, etc. I started on 9/11, so I imported file 09.csv into a very simple, non SRS flashcard program (Remata) and studied it into short-term memory. On 10/11, (1) I loaded file 09.csv into a new Anki deck and reviewed it for the first time and (2) I loaded file 10/11 into Remata and studied it. On 11/11, file 10.csv went into Anki and file 11.csv into Remata, and so on until, I hope, 8/12. I’m curious to see whether I can make it, and what benefits I may reap from this exercise.

Sounds good. I usually use Anki to go through new words as well, simply because I think it’s easier to handle just one program. If I import large volumes from somewhere (like 1000 idioms or something), I usually suspend all of them and then gradually un-suspend these cards at a pace I feel comfortable with. The end result should be roughly the same as yours, so it’s probably just a matter of preference.

Let us know how it turns out, I’m sure I’m not the only one who wants to know.

Hello,

On the 10th day of my endeavour, I’d like to ask your opinion on two questions:

1. When you did your character cramming exercise, did you learn ZH-Your language or Your language-ZH. I’ve started ZH-My language but soon thought that I’d rather walk the less easy path of My language-ZH: the vocabulary sticks better and it’s easier to produce the ZH words.

2. I’ve read that Heisig strongly advises against learning the pronounciation at the same time as the characters. I on the other hand would like to learn the signific as a whole, a bundle of image (character/visual memory/mnemonic), pronounciation (pinyin/acoustic image) and any other information that happens to aggregate (etymology, words built with the character, location of the signific within a broader network of information, etc.). In theory, I find it hard, if not counter-productive, to dissociate meaning and pronounciation. What do you think? I suspect that it’s a rather sensitive subject.

However, now that I’ve configured my Anki deck to learn My Language – ZH (production of the character and the pronouciation), the fail rate tends to climb steeply…

Regards

1) I’m almost exclusively going Chinese-English on my flashcards. I find it too difficult to separate synonyms or near-synonyms going the other way around. Also, my language learning strategy focuses a lot about being able to understand as much as possible, so I don’t mind expanding my passive vocabulary quite a lot and then gradually turning it active by practising. This might be different for beginners who really need words to express themselves, but I feel that I’ve left that stage quite a long time ago. An interesting question is when and how to switch. I have no clear answer.

2) I haven’t read enough about Heisig to understand his arguments. Personally and intuitively, his advice sounds really bad and I would strongly recommend people do the opposite and learn characters and pronunciation as one unit. However, this is just my opinion and I have neither anything to back it up with nor the knowledge to be very sure of my opinion. I learn Chinese to be able to use it and I don’t want to do first A then B and only then be able to use what I know, I want to do A and B in parallel and be able to use what I know immediately. What do you perceive as the main arguments for separating characters and pronunciation?

On second thought, I’ve just asked myself: What do I want to achieve at this stage of my Chinese learning experience and, in particular, with this exercise. Answer: A “quantum leap” in my *reading* ability. Learning characters should make it easier to learn more words faster to achieve this goal. So what I want is recognizing characters and be able to read them (silently). Conclusion: I’ve just reconfigure my Anki deck to learn characters in a way that resembles a reading situation, ie ZH > My language + pronounciation.

I read thin comment after your first comment, but it seems you’re reached the same conclusion as I did. I think reading ability and listening comprehension are more important than being able to recall all words when speaking and writing, at least from an intermediate level and above. You seem to agree and your decision looks sound.

Update after 1 month. I’m on track (about 700 new characters studied in 4 weeks) – I wouldn’t have thought it was even possible! The HOWTO: I used good tools (Anki + usual dictionaries + Yellowbridge for the components), I followed a rather strict method (systematic use of mnemonics built from components) and planning (a fixed number of characters/day drawn from Hoenig’s “Chinese characters”), I used every possible time slots to review (with Ankidroid on my phone), and I kept focussing on the short term (I know I could not sustain such a pace in the long run, but I can try for, say, 50 days, and be happy if can do it for 30 days).

On the other hand, I’ve had to leave aside most of my other Chinese-related activities, but I believe it’s a good investment. In fact, when I read some texts, I can already see a huge difference.

The big caveat is that, if I have swallowed 700 characters – now I will have to digest them. Right now, while reading, I sometimes spot characters that I know I’ve just studied successfully in Anki – but can’t remember its meaning and pronunciation in context. Time and repeated reading should solve this.

The other caveat is that learning characters is just a step, a tool to be able to learn words, of course.

I also believe I started this at the right time. I already knew about 1000 characters, which means I was familiar with most components, many phonetic elements and the general structure of Chinese characters.

Now I think I might as well run for another mile until the symbolic 2000 characters threshold. Then I’ll stop and take the next step, ie read more advanced texts and teach myself lots of useful words, only learning the new characters that appear in new words.

Olle, thanks for the inspiration to start this.

L

Thank you for sharing your progress with us! I’m glad to hear that it’s working well for you. I think you have the right attitude as well, because of course knowing lots of characters won’t enable you to read everything in Chinese, you need lots of exposure as well. However, spending a limited amount of time learning characters like this as an important step on the way is good, I think. Not only does it enable you to decipher more difficult texts, it also makes it even easier to learn even more characters and words. I think everything up to 2000-2500 will provide a serious boost, but after that it depends a little bit on what you’re reading (I have around 4200 unique characters in my deck, but some of them I have never seen in context even though I read quite a lot). Are you aiming for a total of 2000, meaning you have 300 left? Would mind reporting again once you’re done? It would also be interesting to hear what you have to say after you’ve had some time reading a bit more and actually start using what you’ve learnt.

Great tips, thanks! I also use mnemonics to create a story linking all the words I learn in a chapter of a textbook. Each chapter usually has a theme like “weddings”, “recycling” , “moving” etc so I use that as the main theme of my story.

http://www.heinsuniverse.com

Something I’ve been wondering about recently is how to keep the meaning of single characters separate from “real words”. Typically I go from English to Pinyin to Chinese and force myself to write down the Chinese character when learning/reviewing vocabulary. Since English is the first thing I see in my deck, knowing whether it refers to an individual character or real word is tricky.

Actually, I have never tried learning characters in isolation, but I do believe in your holistic and mnemonic approach, so I need to change something about my process. My current level is HSK 4 and I need to double my vocabulary for HSK 5.

Typically I learn the pronunciation and character together, but I would like to experiment with learning individual characters without the pronunciation. I think this would be faster and it will force me to create mnemonics in English. Perhaps this way I can also keep them separate in my brain from “real words”. Then once I learn another 500 characters in visual form, I can go back to the HSK list and quickly put together words with pronunciation, since the mnemonic building blocks are already there. I’ll be using the Memrise character decks and then report back around the end of April with my progress.

It’s time to work smarter, not harder! (Well, maybe a little bit harder.)

I haven’t really thought much about this problem, because at least for me it hasn’t been a problem in practice. The main reason probably is that most words are disyllabic in Chinese, so learning words and characters are usually different things. Learning what character goes in what word is of course much harder, but I think that’s best resolved by input rather than focus studying.

iam studying chinese

ni hao

ni hao…. I began Chinese a few years ago but was disappointed by my results. If you are struggling in the classroom I suggest you try a program outside of the class like this one:

http://a078fis7-9qm2nfkodpitljre8.hop.clickbank.net/

Hi Olle,

Thanks for the great blog, I just recently found it.

I have one question relating to this article. When you are creating a mnemonic for a word, how do work out which meanings to use for each of its component characters? For example the word ‘周到’ which means ‘attentive, thoughtful’ contains the characters 周 and 到。 As both of these characters can mean ‘thoughtful’, it kind of makes sense to think of the word as a combination of two characters with this meaning. On the other hand, we could use some of the more usual meanings of the two characters such as ‘cycle, week’ for 周 and ‘towards, until’ for 到 which may create a more memorable mnemonic. I am not sure which method would be better, can you explain how you would tackle this problem?

One more thing, I have found that I have to write a mnemonic down to make it stick, but it takes longer. Do you write your mnemonics down?

Thanks for your help,

Anthony.

I am not Olle but I think it’s better to use the more unrelated meanings in cases like this. I don’t know whether 周 and 到 can mean thoughtful by themselves but they have meanings such as week and arrive which are useful.

Something like: When the week arrives at its end, we spend a day being thoughtful – which is why we don’t work on Sundays, just sit around being thoughtful.

I sometimes put mnemonics into Anki in a new field. You usually don’t have to write the *entire* mnemonic down, just enough to remember… “thoughtful as week arrives at end” is enough.

I sometimes write mnemonics down. I used to think that it wasn’t necessary, but I’ve found that I take the whole creation task more seriously if I write it down, so I do that most of the time nowadays.

Regarding 周到, I’ve always thought of it as 周 meaning “all around” or “complete” and 到 meaning that you attend “to” something. The dictionary entry says 面面俱到,沒有疏漏, which is roughly in line with this, thinking of 周 as 面面 and 到 as 俱到.

I agree with Tyson that you probably shouldn’t use identical mnemonic representations for different characters.

(P.S. thanks for bumping the comment, Tyson, I had completely forgotten about it)

May I ask where you store your mnemonics? I’ve recently downloaded Anki and I was wondering if there was a way to write down the mnemonic and be able to easily access it.

I have Skritter and use Anki as well, but in your article Learning Chinese words really fast you talk about using spaced repetition software. Do I have to create my own Anki deck to be able to take the words I want to learn and have the benefits of SRS, or is there a template out there that I can use to input words. Thanks

I’m not sure I understand your question, but just to make things clear, Anki and Skritter are both examples of spaced repetition software. They both space their repetitions based on roughly similar algorithms. Thus, if you’re using these programs, you’re already reaping the benefits of SRS. How you want to input cards is a more complicated question, but not directly related to spaced repetition.

Two questions:

1. How do you remember the order of the characters? Associating 糖 (sugar) with 果 (fruit) to get 糖果 (candy) is pretty easy. But I often find that I can’t remember the order. Is it 糖果 or 果糖?My mnemonic is just a visual image in my mind and does have an order. This can also be an issue with remembering identical but switched words like 意愿 and 愿意//合适 and 适合.

2. In your system, does an individual character usually have only one visual representation? For example, 合 means “fit”. Let’s imagine shoving an extremely fat elephant into a cage an he just barely “fits”. Will you use this same fat elephant to remember 合适,适合,and 合并?

I lied. I have one more question. Feel free to combine my two posts if that’s possible.

3. How do you remember characters with more abstract/general/undefined meanings like 然,事, and 物?

I really like this idea for learning words and will be using it soon!

One thing I am curious about is how you have your flashcards/anki cards set up for learning new words. Can you give an example on how you have your cards set up?

Thank you~!

There are numerous different combinations and the answer to your question is very complicated. In essence, it depends on what you want. You can add single characters, words, phrases or sentences depending on what you’re after. You can also show either English or Chinese on the front page (I did mostly Chinese in the beginning because I wanted to boost understanding) or both.

Hi Olle,

I studied 3 yrs of Cantonese when I was younger and throughout the years I’ve improved by myself. My spoken Cantonese is very good, and reading an entertainment newspaper article is good too. (I might not know a few words only) From watching a lot of dramas, karaoke and reading social network sites in Chinese my reading ability has been getting better. My problem is that when I write I forget the word but If a bunch of words were to be in front of me I would know exactly which word I need to use. So I am constantly using the dictionary to look it up.

I’m finally trying to improve my written Chinese. I am writing 4- 6 lines of Chinese in my diary entry. Then the words that I had to look up I would use them in another book and make sentences with it. If I do that along with your mnemonics technique do you think it will work?

I also plan to go through basic Chinese words to improve when I have time as well.

Thank you!!

What you’re describing is very common and is true for everyone to some extent. I can read many, many more characters than I can write and so can most native speakers as well. There are basically two problems you need to fix: 1) remember which character should go in the word and 2) how to write that character. Natural, communicative writing solves part of both problems, but not everything because there will be many characters you simply never write in your diary. I think it’s best to combine this with some SRS, such as Skritter. You could also start using handwriting to write Chinese on your phone or computer! There is an article in the pipeline about this, so stay tuned. 🙂

Hi Olle,

first of all, many thanks for sharing this amazing blog to all of us! Really. I’ve been reading it over the past few weeks, and I liked it quite much, but when I stumbled upon this post, it really blew my mind! I never though about learning with mnemonics in such a systematic manner.

Now, I have one question:

How do you learn a word with multiple meanings (i.e. homonyms, homophones)?

I’m not interested in Chinese specifically, but I’m asking in general. Note that some words have very different meanings, for instance:

– “rose”, 1. a flower, 2. past tense of “to rise”

– “date”, 1. a fruit, 2. a romantic/social appointment

– red/read (homophones)

– buy/bye/by (homophones)

– so on …

You may know one of the possible meanings perfectly well, but usually others cannot be inferred by retrieving this previous knowledge or by guessing. And, by the way, since some words of this kind have more than one important meaning, one can’t just learn one of them!

My guess is that one can link each meaning to a specific mnemonic, but I’m afraid that this would cause many interferences each time you read or listen in retrieving the right meaning.

What do you think? How do you avoid the issue?

Thanks.

I think I usually don’t bother with mnemonics in these cases if I don’t need to. If I know one usage of the word, I find it pretty easy to extend that knowledge to include another meaning. This is done by actually using the language (including reading and listening, of course). The fact that I already have that word (albeit with another meaning) stored in my brain makes it relatively easy to absorb the new meaning. Thus, my answer here is somewhat theoretical since I don’t actually do this, but incorporating two meanings in the same mnemonic shouldn’t be hard. Picture a rose that rose out of the ground or something?

I am currently staying in China and thinking about doing HSK 6 in March which gives me roughly 3 months for preparation. I did a mock HSK 5 test and passed without problems but the vocabulary lists seem to include about 2800 words I do not know yet.

Olle, can you recommend your method of just learning words without context first or should I walk the extra mile and at least look for an example phrase for each word? How many characters per day would you recommend given that I do not need to be done in a mere 5 days like you?

Thanks to this blog I already know how to fish, that is, I probably know most of the characters that will occur in the course of learning 😉

Thanks! Keep up the good work!

I think it depends on what kind of word it is. It’s fine to learn some nouns and other words that are obvious how to use without context. For other more context-bound words, I strongly suggest using short phrases. Of course, if your goal is to pass a reading or listening test, doing away with the phrases might be possible, but it’s not recommended for learning in general. Regarding how many you should learn per day, that entirely depends on how much time you have and what you want to accomplish. Spread it out evenly with slightly more in the beginning (it will pile up). Don’t drown. Good luck!

Thank you so much, Olle!

Being in China will hopefully provide me with the context even if I focus on single words for now.

One follow-up question: Do you make use of the pictures/mnemonics for each character when coming up with a mnemonic for the whole word? I feel it might help to at least recreate the pictures while learning; on the other hand you definitely do not want to confuse an individual character’s mnemonic with the mnemonic for the whole word, right?

I don’t use mnemonics for everything, I do it on a need-to basis. On the other hand, I’ve used mnemonics a lot and often some kind of picture emerges in my head just by looking at it, provided that I know what the components mean (which is almost always the case nowadays).

Hi olle my name is Hamson .

I am first premdical students at shangdong university ..learning the hanzi was a very diffucuilt for me i often fail several tests and i only pass few with memorise steps .But i usually forget them after the day of tests b,my method of studing is write a hanzi ten and 20 times …still forget

can you tell me writing is better or using memonics is more better?i get tired of writing and writing HSK4 vocub

Is there any institute in Singapore or online training institute to teach mnemonics technique and guide you to learn 400 Chinese words per day? Or can I take your help for building the technique? Thanks

I’m not very familiar with educational institutions in Singapore, so I don’t know!

In short, Chinese characters as information-rich morphemes are highly compatible and productive in word formation.

e.g. 牛肉 豬肉 果肉 (cattle flesh, pig meat, and fruit meat) instead of remembering a new set of words (beef, pork, and pulp). :p

I know! This is makes acquiring advanced vocabulary so much easier. I remember when I started reading up on linguistics and especially phonetics in Chinese and realised how easy it was compared to English. I mean, which is harder to learn 塞擦音 or “affricate”? Medical terminology is a good example too. In English, you need to know Greek and Latin to make sense of many words, whereas in Chinese, they often make sense even just by knowing the basic components.

Is 觉 (jiao4) actually a bound morpheme? I agree that most of the time it appears in the context of 睡, but there seems to be one example where it is on its own: 祝你一个好觉 (“May you sleep well” or, more literally, “I wish you a good sleep”)

Yes, the context is sleeping, but 睡 seems to not be required here. Unless, of course the sentence is not grammatically correct. Though, I believe I learned the phrasing from a native speaker.

While there could certainly be native speakers who accept that sentence, I checked with a native teacher from Beijing and she said it sounds outright wrong without a 睡. Searching for the phrase gives only two hits, and even with a wider search, I can’t really find much reason to believe phrases like that work or are common!

Ok, thank you!