Chatting online is seldom considered a method for learning Chinese, but it has several unique benefits. While generally regarded as a frivolous waste of time, text-based chatting has a place in even the most serious learning strategy.

Chatting online is seldom considered a method for learning Chinese, but it has several unique benefits. While generally regarded as a frivolous waste of time, text-based chatting has a place in even the most serious learning strategy.

Chatting and texting combine the communicative aspects of conversations, while still offering some of the advantages of the written language, such as the ease of looking things up, time to think before you reply, and the option to review the exchange later.

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcast, Overcast, Spotify, YouTube and many other platforms!

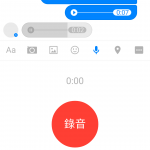

In this article, I’m focusing on text chatting on your phone or computer, but many of the benefits of doing this overlap with using voice messaging, a feature which is also available in most apps that offer text chatting. I wrote more about this here: Using voice messaging as a stepping stone to Chinese conversations

Using voice messaging as a stepping stone to Chinese conversations

12 reasons why chatting is underrated as a learning tool

Let’s have a look at some of the benefits of chatting in Chinese, some of which are hard to access in any other way:

Communicative – The purpose of language is to communicate with other people, and even though other forms of writing can also be communicative, chatting is more immediately communicative. When you write a diary entry, an email or a blog post in Chinese, it’s also communicative, but the communication won’t be two-way until after you’re done, if ever. Chatting, on the other hand, is a constant back-and-forth which feels more communicative than any other type of writing, which makes it great for learning!

Communicative – The purpose of language is to communicate with other people, and even though other forms of writing can also be communicative, chatting is more immediately communicative. When you write a diary entry, an email or a blog post in Chinese, it’s also communicative, but the communication won’t be two-way until after you’re done, if ever. Chatting, on the other hand, is a constant back-and-forth which feels more communicative than any other type of writing, which makes it great for learning! Meaning-focused – Much of Chinese writing practice is done for no other purpose than to improve your Chinese. Maybe you’re writing example sentences using a new grammar pattern, a dialogue to practise new vocabulary, or a self-presentation as part of an assignment in your course. The goal in these types of activities is on the language, not on conveying meaning. When chatting, however, you might write similar sentences, but you do so to say something interesting or important! For more about meaning-focused learning, see Analyse and balance your Chinese learning with Paul Nation’s four strands.

Meaning-focused – Much of Chinese writing practice is done for no other purpose than to improve your Chinese. Maybe you’re writing example sentences using a new grammar pattern, a dialogue to practise new vocabulary, or a self-presentation as part of an assignment in your course. The goal in these types of activities is on the language, not on conveying meaning. When chatting, however, you might write similar sentences, but you do so to say something interesting or important! For more about meaning-focused learning, see Analyse and balance your Chinese learning with Paul Nation’s four strands. Bite-sized writing – Getting started writing in Chinese can feel daunting, especially if you’re a beginner. You might try writing a diary entry, a short story or a blog post, but you get stuck on the first sentence because you don’t know how to begin. The problem is that you have bitten off more than you can chew. Chatting is meant to be relaxed so makes you feel less pressure to write something good. Write one sentence, get a reply, write something in return, and after a while, you will have practised much more writing than you would have if you kept to your diary, story or blog. When you do want to write something longer, check out 20 tips and tricks to improve your Chinese writing ability.

Bite-sized writing – Getting started writing in Chinese can feel daunting, especially if you’re a beginner. You might try writing a diary entry, a short story or a blog post, but you get stuck on the first sentence because you don’t know how to begin. The problem is that you have bitten off more than you can chew. Chatting is meant to be relaxed so makes you feel less pressure to write something good. Write one sentence, get a reply, write something in return, and after a while, you will have practised much more writing than you would have if you kept to your diary, story or blog. When you do want to write something longer, check out 20 tips and tricks to improve your Chinese writing ability. Time to think – Everything goes so fast in a spoken conversation; you need to figure out what the other person is saying and formulate your responses at the same time. This can be stressful and also limits your ability to use words other than those that immediately come to mind. When chatting, you can take as much time as you want to understand what the other person is saying and how to respond, choosing among different options and trying out new ways of expressing yourself. This is a good opportunity to review grammar patterns you think should work but aren’t entirely sure of.

Time to think – Everything goes so fast in a spoken conversation; you need to figure out what the other person is saying and formulate your responses at the same time. This can be stressful and also limits your ability to use words other than those that immediately come to mind. When chatting, you can take as much time as you want to understand what the other person is saying and how to respond, choosing among different options and trying out new ways of expressing yourself. This is a good opportunity to review grammar patterns you think should work but aren’t entirely sure of. Bite-sized reading – It takes two to tango, so even if your writing is an important aspect of chatting to learn Chinese, reading is at least as important. Opening a book and facing a wall of Chinese characters can be daunting even for more advanced students, but reading what the person you chat with is saying feels more manageable. Bite-sized reading is not enough, but it’s a great start!

Bite-sized reading – It takes two to tango, so even if your writing is an important aspect of chatting to learn Chinese, reading is at least as important. Opening a book and facing a wall of Chinese characters can be daunting even for more advanced students, but reading what the person you chat with is saying feels more manageable. Bite-sized reading is not enough, but it’s a great start! Colloquial language in written form – One unique advantage of text chats is that you can see the spoken language in written form. People don’t type exactly what they would have said in a conversation, but it’s much closer to naturally spoken language than the dialogues in a film or novel, not to mention your textbook. This allows you to see words written down that you have previously only heard in spoken conversations and might have struggled to understand or link to the written language. The only other good way to do this is to read comics in Chinese, which often also has very colloquial language in written form.

Colloquial language in written form – One unique advantage of text chats is that you can see the spoken language in written form. People don’t type exactly what they would have said in a conversation, but it’s much closer to naturally spoken language than the dialogues in a film or novel, not to mention your textbook. This allows you to see words written down that you have previously only heard in spoken conversations and might have struggled to understand or link to the written language. The only other good way to do this is to read comics in Chinese, which often also has very colloquial language in written form. Chance to spot elusive words – It’s possible to miss common words or expressions when listening, even when they are present in the input. This is not strange, considering how many things your brain needs to do at once to understand spoken Chinese. But then, one day, you suddenly notice the word or expression and wonder how on earth you didn’t notice it earlier. I had this experience with the phrase 真的假的 (zhēnde jiǎde), meaning “Is this true?” or “Really?”, which I probably was exposed to dozens of times in spoken conversation without noticing, but then after seeing it in writing only once, started to hear everywhere.

Chance to spot elusive words – It’s possible to miss common words or expressions when listening, even when they are present in the input. This is not strange, considering how many things your brain needs to do at once to understand spoken Chinese. But then, one day, you suddenly notice the word or expression and wonder how on earth you didn’t notice it earlier. I had this experience with the phrase 真的假的 (zhēnde jiǎde), meaning “Is this true?” or “Really?”, which I probably was exposed to dozens of times in spoken conversation without noticing, but then after seeing it in writing only once, started to hear everywhere. Opportunity to look things up – In a spoken conversation, you can’t just hit the pause button, transcribe what the other person is saying and then look it up in a dictionary. And even if you sometimes can, such as when practising with a tutor or language exchange partner, it still has a significant impact on the conversation. When chatting online, however, this is not an issue; you already have everything in writing so it’s easy to look things up, and you also have the time to do so without disrupting the conversation.

Opportunity to look things up – In a spoken conversation, you can’t just hit the pause button, transcribe what the other person is saying and then look it up in a dictionary. And even if you sometimes can, such as when practising with a tutor or language exchange partner, it still has a significant impact on the conversation. When chatting online, however, this is not an issue; you already have everything in writing so it’s easy to look things up, and you also have the time to do so without disrupting the conversation. Option to review the conversation later – When speaking, you can’t go back later to check what you could have done better (unless you’re using voice messaging, of course), but this is easy with a text chat. If you’re chatting with someone who’s not obliged or interested in helping you improve your Chinese, you can share your conversation with someone who is, such as a tutor or language exchange partner, and ask them how you could improve. Naturally, it’s always good to be aware of privacy issues, so get consent or anonymise the chat before you share it.

Option to review the conversation later – When speaking, you can’t go back later to check what you could have done better (unless you’re using voice messaging, of course), but this is easy with a text chat. If you’re chatting with someone who’s not obliged or interested in helping you improve your Chinese, you can share your conversation with someone who is, such as a tutor or language exchange partner, and ask them how you could improve. Naturally, it’s always good to be aware of privacy issues, so get consent or anonymise the chat before you share it. Safe behind your screen- Another significant advantage of chatting over face-to-face conversations is that it feels safer and less stressful. If you are an introverted learner or just don’t feel ready to talk with someone live, chatting can be a great stepping stone to real conversations, even safer than voice messaging, all while keeping to the same type of language that you’ll use in an actual conversation later.

Safe behind your screen- Another significant advantage of chatting over face-to-face conversations is that it feels safer and less stressful. If you are an introverted learner or just don’t feel ready to talk with someone live, chatting can be a great stepping stone to real conversations, even safer than voice messaging, all while keeping to the same type of language that you’ll use in an actual conversation later. Getting to know people and making friends – Even though most people experience less anxiety when chatting online compared to face-to-face spoken conversations, it’s still a social activity. By keeping in touch with people you’ve met offline or by getting to know new people online, chatting allows you to maintain and build relationships. This has many benefits beyond language learning!

Getting to know people and making friends – Even though most people experience less anxiety when chatting online compared to face-to-face spoken conversations, it’s still a social activity. By keeping in touch with people you’ve met offline or by getting to know new people online, chatting allows you to maintain and build relationships. This has many benefits beyond language learning! Fun and engaging, – While this is highly subjective, many students feel that writing longer texts is less fun and engaging than chatting with someone online. This could be due to some of the factors mentioned above, or because they have a more favourable view of chatting online than they do of writing diary entries, short stories or blog posts. Having fun is important!

Fun and engaging, – While this is highly subjective, many students feel that writing longer texts is less fun and engaging than chatting with someone online. This could be due to some of the factors mentioned above, or because they have a more favourable view of chatting online than they do of writing diary entries, short stories or blog posts. Having fun is important!

I think the last point is perhaps the most important one. Traditional education has somehow embedded itself in our minds and some people think that fun must somehow be less serious. Studying can be fun at the same time as being very serious indeed.

Writing in Chinese beyond chatting online

Chatting online can be the ideal form of practice in some situations, with clear benefits over more traditional reading and writing, or even listening and speaking. That doesn’t mean that it can replace these, however. As mentioned in point five in the list above, bite-sized learning is a great start, but to build up an intuitive feel for how Chinese works, you need to go beyond reading isolated sentences, because this will never give you the amount of exposure you need. For that, you need extensive reading, which is hard to do in a text chat.

Writing is also about more than producing one-line responses to questions or asking short questions yourself. The foundation of writing proficiency in Chinese is reading (see above), but you also need to practise writing yourself. If you’re ready to move beyond chatting online, I’ve compiled my best advice for improving your writing ability here: 20 tips and tricks to improve your Chinese writing ability

Editor’s note: This article, originally published in 2013, was rewritten from scratch and massively updated in December 2023.

Tips and tricks for how to learn Chinese directly in your inbox

I've been learning and teaching Chinese for more than a decade. My goal is to help you find a way of learning that works for you. Sign up to my newsletter for a 7-day crash course in how to learn, as well as weekly ideas for how to improve your learning!

9 comments

Do you know anywhere online I can find people to chat with?

I suggested some ways in this article: Language is communication, not only an abstract subject to study

Greetings from France!

Great article! Chatting allowed me to learn a lot of new vocabulary. I suggest ‘Hello Talk’ app on iPhone for that. It allows English speakers to chat with Chinese natives – and there are TONS of them! You’ll soon have too many chinese friends who want to chat with you. I really give 10/10 to this app and I’ve been using it everyday. It support hanzi to pinyin and also translation, so learning new vocab is extremely convenient.

Another option is italki.com, which also allows you to chat with chinese people and get them to correct your written texts.

Completely agree with the conclusion that “chatting definitely has a place in the daily routine of the serious language learner”.

Regular text chatting helped me personally to develop confidence and basic communicative competence in Swedish.

I have also been using it as part of a strategy to give my Mandarin students opportunities to transfer learning from the classroom to the real world. This, in turn has resulted in obvious motivation boosts for many students. I have, however, noticed that the more confident ones tend to prefer moving to audio and video MESSAGING after a while in situations where that’s appropriate. This still isn’t 100% real-time communication, in the sense that f2f conversations are, so just like text chatting it is great for developing complexity and adds the element of pronunciation-related practice and feedback.

Anyway, your post is absolutely spot on Olle, and I would definitely encourage learners of any language to make use of non-real time (as well as real-time) chatting for the multiple reasons and benefits you’ve included here. It is an easy and fun way to make language learning an integrated part of your life.

Thx,

Angel