I recently published a guide for how not to teach Chinese characters to beginners, which was a rant based on a decade of observed worst practices in Chinese classrooms. Naturally, it also reads as a guide for how it should be done; just reverse the wording.

I recently published a guide for how not to teach Chinese characters to beginners, which was a rant based on a decade of observed worst practices in Chinese classrooms. Naturally, it also reads as a guide for how it should be done; just reverse the wording.

Most of the things I mentioned in the article aren’t very controversial, but there were two things that merit further discussion, either because the issue in question is more nuanced than I gave it credit for, or because it’s easy to misunderstand what I wrote.

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to this article:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcast, Overcast, Spotify and many more!

The first point many took issue with is about learning the names of the strokes in Chinese characters. After a bit of reading, debating and thinking, I haven’t really changed my mind, but I do acknowledge that there’s much more to this question than I could fit into a one-paragraph rant about it. In this article, I will explore this question in more detail.

The other point many had questions about is mostly about what words we use when we talk about Chinese characters: There’s a widespread belief that “radical” means “character component”, whereas the radical is actually just one specific component in each character that is used to sort it in dictionaries. Teaching components is great, but requiring students to learn which of them is the radical is not. I will return to this question in a future article.

Should you learn the names of the strokes in Chinese characters?

The short, general answer is “no, you don’t need to learn the names of the strokes in Chinese characters”. The main reason is that as a beginner, you have many things to learn that are far more important than that.

In other words, it’s a matter of priority. You can always argue that anything is worth learning, but the question is not “is learning this useful?”, but rather “is learning this the most useful thing right now?”

I would argue that the answer to the latter question is almost always “no” when it comes to the names of strokes.

Learning stroke names by naturally absorbing them

But what if the stroke names are not taught explicitly, but rather learnt naturally through exposure?

For example, if the teacher writes a lot on the board and always calls out the names of the strokes, as a student, you would then learn what these words mean, without having to study them explicitly.

I see no serious issues with this way of teaching the names of strokes, apart from some practical limitations and a wider question about handwriting in the classroom that I will get to in a bit. Being able to hear what the teacher writes can be good if the teacher obscures the board when writing, if you have poor eyesight and so on.

The problem is that this requires intense immersion. In order to learn a word through exposure, we need to hear it not once or twice, but ten, twenty or thirty times. If you study Chinese a few times a week, learning something liket his will take a while and will be far from effortless.

The problem is that this requires intense immersion. In order to learn a word through exposure, we need to hear it not once or twice, but ten, twenty or thirty times. If you study Chinese a few times a week, learning something liket his will take a while and will be far from effortless.

Unless the strokes are taught explicitly, the risk is also that you won’t be very clear about what the key part of each stroke is: Is it the direction? Or the angle of the slope? Something else? Naturally, if repeated enough and enough time is spent on writing, the stroke names will be absorbed in this way.

Should character writing be taught in the classroom?

Or maybe we should ask an ever more fundamental question: Should handwriting be taught at all?

I think the answer is yes, unless we’re talking about a situation where oral proficiency is the only goal. As I have discussed elsewhere, this doesn’t mean that characters should be taught from day one, but if we’re teaching the written language, I think teaching handwriting should also be done. There’s much more to handwriting than stroke names, though, see for example:

But if the names of the strokes are to be taught, how should it be done?

When you know nothing about characters, some hand holding through a few characters just to learn how it’s done and what to pay attention to is in place. This includes everything from stroke order to character composition. After the basic concepts have been learnt, though, I think teaching how to write each character in class is a waste of precious time.

I think this is mostly a vestige of traditional teaching formed before the digital age. Before the advent of nifty apps, a practical way of teaching stroke order was to simply call out the strokes so the students know which stroke comes next. This is of course difficult if they don’t know the names of the strokes.

But the fact is that as a student, it’s very easy to look up any character in a dictionary, where you can have stroke order animations, learn more about the character and so on. There are plenty of resources for learning stroke order available online, just check this article:

All the resources you need to learn and teach Chinese stroke order

In a modern, second language setting, there is no need to write large amounts of characters in class, one stroke at a time. Teach the principles of stroke order, not stroke order for each character.

Another reason not to put the emphasis on strokes is that they don’t mean anything in themselves, one by one. This is in difference to components, which usually have a function in the character and can help students understand and remember it better. Again, this is a matter of priority. If the teacher emphasises strokes, students will get the impression that strokes are more important.

Declarative vs. procedural knowledge

There’s a strong tendency in traditional language teaching to focus on declarative knowledge. To put it briefly, declarative knowledge is about explicitly explaining the language using correct terminology. Many native speakers have a poor declarative knowledge of their own language, but can nevertheless use it fluently.

Here are some examples of declarative knowledge relevant for Chinese learners:

- Explaining the usage of 的 in English

- Describing how Pinyin j/q/x are pronounced

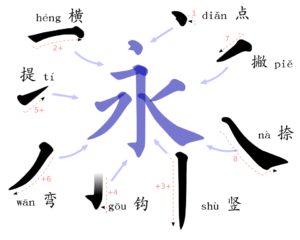

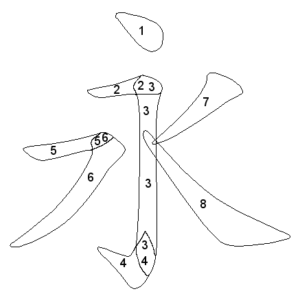

- Naming the strokes in a the character 永 (yǒng)

I’m not saying that this kind of knowledge is useless. If you know that you’re going to talk about something a lot, you might as well learn some words for doing so. I even wrote an article about how to talk about Chinese characters in Chinese:

But focusing on, or even worse, assessing declarative knowledge misses the point of learning a language, which is to be able to communicate. Declarative knowledge is only useful if it indirectly also leads to procedural knowledge. This link is much weaker than most teachers think!

Procedural knowledge is about being able to use the language, so let’s look at the list above but shift the focus:

- Using 的 in a sentence correctly (rather than explaining how it’s used)

- Pronouncing Pinyin j/q/x clearly (instead of describing the sounds)

- Write clear, legible characters (not naming the strokes in them)

In general, I think very good reasons are needed to emphasise declarative knowledge over procedural knowledge in a language learning context.

When learning the names of the strokes makes sense

Like I said above, there are certain cases where teaching the names of the strokes in Chinese characters makes sense, but they are rather limited:

- If you learn calligraphy, how each stroke is written is quite important, and since the end goal of what you’re doing is writing beautiful characters, it makes sense to learn the names early on.

- If you’re immersion classes, especially if you’re not an adult, and writing by hand is an important part of the curriculum. Since the stroke names will be used a lot, you will have a better chance of just absorbing them by exposure. Still, for the well-being of the students, I hope this class is rather limited in scope and only a small part of the immersion experience.

- If you’re an advanced student. My previous article was about teaching characters to beginners, but more advanced students certainly need to know the basic stroke names. They are part of the language and also appear in many idiomatic phrases and expressions. However, it’s likely that you will have picked this up over the years it took you to reach an advanced level, without anyone having to teach you the names.

Keep it simple

As a teacher, if you’re going to teach the names of the strokes, keep it as simple as possible. The most basic 7-8 strokes will do just fine. I’ve seen teachers go through stroke names most native speakers don’t know (I checked), sometimes more than thirty, which borders on the outrageous. Consider what the students really need to know, and use only those names; simplify if necessary.

Conclusion

To summarise, I think that in most foreign language classrooms, the names of the strokes should not be taught, not because they are unimportant, but because there are so many other things the students should focus on. Handwriting should make up a very small part of the course and the names of the strokes only make up a small part of handwriting.

If stroke names are taught, they should be taught through exposure. Giving the names of the strokes in various characters is not an okay way to assess knowledge of Chinese characters.

Focusing on stroke names puts the emphasis on form, on something rather meaningless, as opposed to function, on components that mean something and help students understand characters.