Estimated reading time: 7 minutes | Audio version available on Patreon

When discussing a topic as complex as language learning, we often use metaphors to help us make sense of the learning process.

We’re trying to use what we already know to understand how to tackle a new challenge.In other words, we hope that what we know about learning something else will transfer well to learning Chinese.

In this article, I will explore two ways of looking at language learning. This is somewhat oversimplified, but I hope that it will illustrate that which metaphor you use matters and learning languages isn’t really like learning anything else.

Learning to unicycle and learning anatomy

I have chosen two areas unrelated to learning Chinese, which I will use to highlight some important aspects of learning languages. As we shall see, they do have some things in common, but language learning can be said to be a combination of both.

- Learning to unicycle is actually not as hard as most people think; it’s just that few people give it a serious try and most who do go about it the wrong way. Regardless of what method you use to learn, the key to success lies in practising the exact activity you want to improve: unicycling. Reading books about it won’t help at all, and having someone give you advice might help, but only if you also practice a lot. Looking at other people unicycle can help, but is similarly limited. You improve by trying over and over. When developing skill like this, nothing beats deliberate practice, where you deliberately challenge yourself and do your utmost to improve. Compare this to repeatedly doing things you’re already good at or practising without a clear goal. See the references to Ericsson’s work below under further reading for more about this.

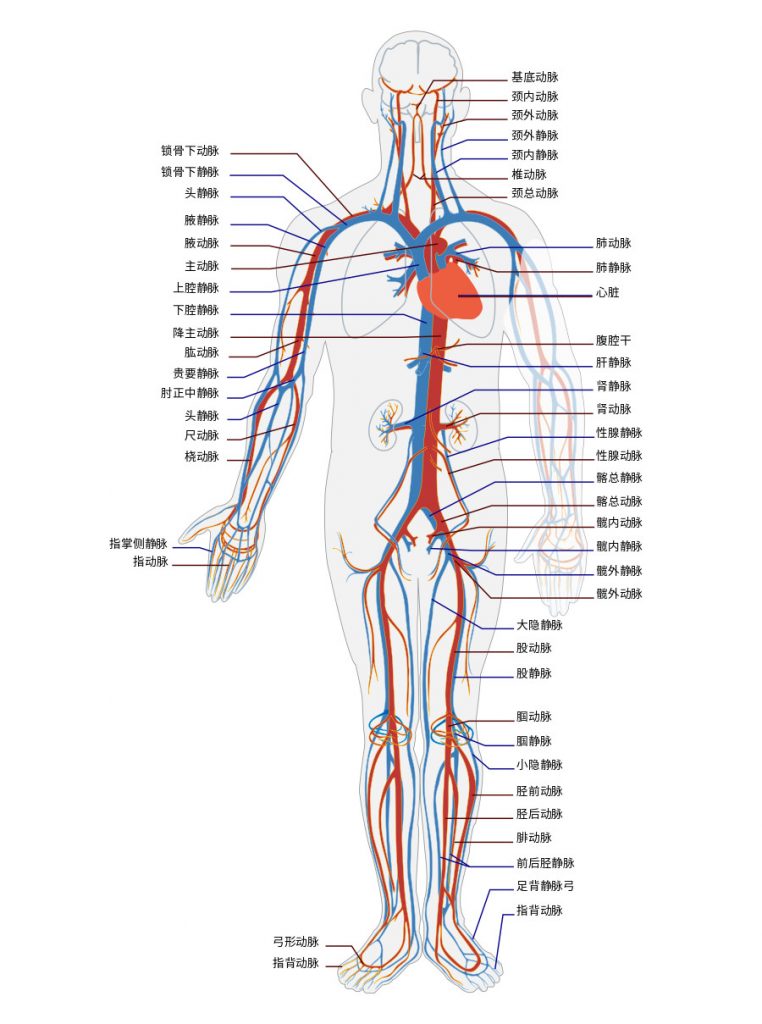

- Learning anatomy is in a sense the opposite. Learning from books, or studying real and artificial models is the way to go. You learn by observing, reading, listening or whatever you prefer. You don’t learn by doing, except if the doing is something done to reinforce what you have already learnt. The tricks you learn to remember all the names of muscles, bones and tendons, along with how they interact, can be easily applied to most other knowledge-based subjects. Meaningful/holistic learning, mnemonics and so on. In fact, I often use anatomy as an a analogy for remembering things, because it’s a good example of where it really helps to have a skeleton to attach everything to! The main point is that you learn anatomy by absorbing and retaining.

These activities can be said to make up the extreme ends of a spectrum running from skill-based to knowledge-based. While there might be some knowledge in unicycling and some skill in anatomy and, they are very different. The first is about practising and doing, the other is about absorbing, understanding and retaining.

Learning Chinese is like learning to unicycle

There are many aspects of learning Chinese which are more like learning to unicycle than learning anatomy. For example, pronunciation is largely a skill that you have to develop. Naturally, it’s not only about motor skills and being able to move the right parts of your speech apparatus the right way, but it’s still more similar to learning to unicycle than learning anatomy.

Knowing the definition of an aspirated affricate (such as Pinyin “c”, “ch” and “q”) and the names of the involved parts of your mouth won’t enable you to pronounce it correctly. It will help a little bit, but only if you also practice a lot. Just like advice about unicycling only works if you pair it with tons of practice.

The same thing can be said about some other areas of learning Chinese, such as handwriting (not including remembering the components and composition of the characters) and to a certain extent also speaking (fluency) and writing (composition). They do of course rely on knowledge as well, but constructing new sentences based on what you already know is closer to learning to unicycle than it is to learning anatomy and you will benefit from the same type of practice.

Learning Chinese is like learning anatomy

Learning Chinese is like learning anatomy

Then there are many aspects of learning Chinese that are like learning anatomy. Some of the more obvious ones are basic vocabulary and grammar patterns, not including actually using them in conversations.

Here you can make use of the same strategies that are valid for learning anatomy, so connecting things together, understanding what you’re learning and using mnemonics will work well.

The goal is to create an interconnected web of knowledge where each new thing you learn is connected to something you already know, in a manner that makes sense, preferably based on how the language actually works.

You can zoom out, zoom in and pan around to see how each piece fits together with the whole, how it can be broken down into familiar components and how it related to other similar nodes in the network. Such a web still needs maintenance, but that’s true for skills as well.

Language learning is a combination of both

I find that one of the most fascinating aspects of learning languages is that it combines skill and knowledge to such a large extent. As we have seen, none of the metaphors work well for all aspects of learning, but can say something about some of them. I think most people would agree that learning Chinese is not only skill like unicycling, but neither is it knowledge-only like anatomy.

Different people probably put effective language learning on different points on the spectrum. Those who advocate speaking from day one and think it’s important to always interact with native speakers would probably say that it’s the procedural aspect of learning that is the most important part. You learn by doing and if you can’t do something with what you learn, it’s useless. Many polyglot bloggers are in this camp. I think this is a valid argument.

But then there are people who think that learning a second language should be done more like learning a first language, where we spend a significant amount of time listening before we speak and, later, reading before we write. How can you learn something new by speaking yourself? You can only say things your brain has collected enough data about to be able to say, so saying it is the result of learning, not the cause of it (see Krashen for more about this). This group also has a point. I don’t mean to say that language learning is like exactly learning anatomy; obviously it involves more than just absorbing things.

So, which is it, unicycling or anatomy?

I’ve tried to place myself in this debate for a long time, but have found it difficult to come to a conclusion. I think both arguments are valid, but simply saying that and placing myself squarely in the middle is very unsatisfactory and doesn’t really explain anything.

Using the analogies of unicycling and anatomy above, I think I can give a better answer, and one that fits my own experience and knowledge. This is simply that language learning is combination of skill and knowledge, and that different aspects therefore require completely different approaches. It’s not that language learning is somewhere on the spectrum, it’s that different aspects of learning are on different parts of the spectrum.

A balanced approach

For example, it seems blindingly obvious to me that in order to achieve clear pronunciation, you have to practice. No amount of input is going to enable you to say things correctly as an adult unless you also practise. The same can be said about using grammar patterns, finding words quickly enough to speak fluently and negotiating your way around linguistic hurdles when you interact with native speakers. These areas are, among others, very much like learning to unicycle. You won’t get there if you don’t practise.

However, there are also many areas where simply doing is not enough. If you spend most of your time speaking, you stand little to no chance of achieving good pronunciation either, because you need large amounts input too to figure out how things are actually pronounced.

The same is true for grammar as well. No amount of speaking Chinese will give you a good intuitive feel for how grammar patterns and words are used, that comes from listening to other people or reading. Conversations are useful in this regard, but mostly because they also provide you with listening practice.

Input is more important than output

That being said, as time goes by and I learn/teach more, the more I have moved towards the input camp. It’s not that I think that what I said above is not true, some aspects rely more on practice and some rely more on input, it’s just that the need to practise usually comes after the need for input, and the need for input is in general much larger (takes more time).

I’ve also found that these aspects of learning Chinese take a lot longer to master. Asking questions in Chinese is much easier than understanding the answers. I addressed this in my article about which was more important, listening or speaking, when learning Chinese.

Conclusion

So, what should you take with you from this article? I think the most important part is to realise that language learning is a very complex process and that different parts of it require different approaches. Learning Chinese is a little bit like learning a new sport, but it’s also a little bit similar to studying a subject like anatomy.

When learning vocabulary and sentence patterns, you can borrow freely from other knowledge-based subjects such as anatomy, but if you want to speak more fluently, approaches learned from practising other skills such as unicycling will be more useful.

Where do you place yourself on this spectrum? I realise that not all readers will buy the idea that the spectrum even looks the way I have described it here, or even that there is a spectrum in the first place, but if so, I’d be interested in hearing what you think!

Further reading

Ericsson, K. A., Smith, J. (1991). Toward a general theory of expertise: Prospects and limits.

Input Hypothesis – An article on Wikipedia introducing Krashen’s hypotheses. Not the most comprehensive introduction, but it does give you some information as well as plenty of further reading if you’re interested.

Benny Lewis’ TEDx talk: Speak from Day One.

Tips and tricks for how to learn Chinese directly in your inbox

I've been learning and teaching Chinese for more than a decade. My goal is to help you find a way of learning that works for you. Sign up to my newsletter for a 7-day crash course in how to learn, as well as weekly ideas for how to improve your learning!

1 comments