As an independent learner of Chinese, you need to keep three questions in mind: what to learn, how to learn it and how much time to spend on each area.

As an independent learner of Chinese, you need to keep three questions in mind: what to learn, how to learn it and how much time to spend on each area.

What to learn is the most important question, because you don’t want to miss essential things, and you don’t want to waste time learning useless things you could have skipped.

But how do you know which is which? For example, should you learn how the radicals are pronounced?

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode (#201):

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Overcast, Spotify, YouTube and many other platforms!

Radicals, character components and pronunciation

There’s much confusion regarding the words we use to talk about Chinese characters. What is a radical? What is a character component? What’s the difference between the two? Does it matter?

If you’re new to learning Chinese characters and don’t know much about how they work, I suggest you check out the article and podcast series starting here first: The building blocks of Chinese, part 1: Chinese characters and words in a nutshell

The building blocks of Chinese, part 1: Chinese characters and words in a nutshell

What we choose to call something doesn’t affect the thing described, but when giving advice about learning Chinese, it’s important to ensure that we’re talking about the same thing.

Let’s get the terms straight:

- A character component is any part of a compound character. Thus, we can say that 好 (hǎo), “good”, has two components, and that 想 (xiǎng), “to think”, also has two components, although one of them is a compound in itself. With this broad definition, there is no definitive list of all character components. Each component can have one or more functions, so might for example provide information about sound, meaning or both. For example, in 好, both 女 (nǚ), “woman”, and 子 (zǐ) “child; son”, indicate meaning. In 想, the top part 相 (xiàng), “appearance”, indicates the sound and the bottom part 心 (xīn), “heart”, indicates the meaning. Some components have no function and are the result of character evolution and corruption over thousands of years.

- A radical is a character component with a very specific function, namely to index that character in a dictionary to make it easier to find. Each character has one and only one radical. There are different lists of radicals used in different periods and regions, but the most widely used one today is the 214 康熙 (Kāngxī) radicals. It’s important to note that which component is the radical was decided long after the characters were created and don’t tell us much about the other functions that the component might have.

Here are some characters:

- 知 (zhī), “to know”, contains two functional components: 矢 (shǐ), “arrow”, and 口 (kǒu), “mouth”. The first gives the sound (similar initial, same final, different tone) and the second gives the meaning (presumably knowledge is transmitted by speaking).

- 扣 (kòu), “to fasten”, also consists of two functional components: 扌, a variant of 手 (shǒu), “hand”, and 口 (kǒu), “mouth”. It’s not surprising that the first is related to the meaning of the character (fastening something with your hand) and that the second is related to the pronunciation (only the tone is different).

- 和 (hé), “and”, also has two components: 禾 (hé), “grain”, and 口 (kǒu). Here, it’s also easy to see that the first is a sound component (identical pronunciation) and the second is a semantic component (the original meaning of this character is “to mediate”, which is a verbal activity).

So, can you guess which component is the radical in each character?

No, you can’t.

Remember, radicals have nothing to do with the function of the components and were instead invented to make it possible to index characters in dictionaries. Here are the answers:

- 知 (zhī), “to know”, the radical is 矢, a phonetic component on the left.

- 扣 (kòu), “to fasten”, the radical is 扌, a semantic component on the left.

- 和 (hé), “and”, the radical is 口, a semantic component on the right.

That being said, the radical is often a semantic component on the left, but as I have just shown, this is far from always the case. The main takeaway here is that “radical” is a role that a component plays in a specific character. 口 is in all three characters above, but it’s only the radical in one of them.

So why are we still talking about radicals then?

That’s a great question! The answer is that we shouldn’t; there is no reason to learn which component plays the role of radical in a compound and there’s no inherent value in learning a list of radicals. You need that information to look up unknown characters in a paper dictionary, but this is a completely obsolete skill for most students.

So why do people talk so much about radicals, then? And why is Kickstart your Chinese character learning with the 100 most common radicals one of the most popular articles on Hacking Chinese?

Kickstart your Chinese character learning with the 100 most common radicals

The reason is practical: Most people don’t understand what radicals are and confuse them with character components. You will hear people say that a character consists of these two radicals, or they want to learn the most common radicals because they realise that learning the building blocks of characters is very important.

If I want to reach normal students and teachers, I need to include the word “radical”, because 99% of the time, students who say “radical” actually mean “character component”.

Learning radicals is useful, but not because they are radicals

That being said, learning common radicals is still useful, not because they are radicals, but because they also happen to be common semantic components. Learning which component is the radical in a specific character is useless in a modern setting, but learning about the function of each component is very useful.

Thus, a list of the most common radicals is a convenient way to access common character components and reach many students who will benefit from that list at the same time. That list overlaps with a potential list of semantic components to a fairly high degree, but there are of course many common character components that are never used as radicals.

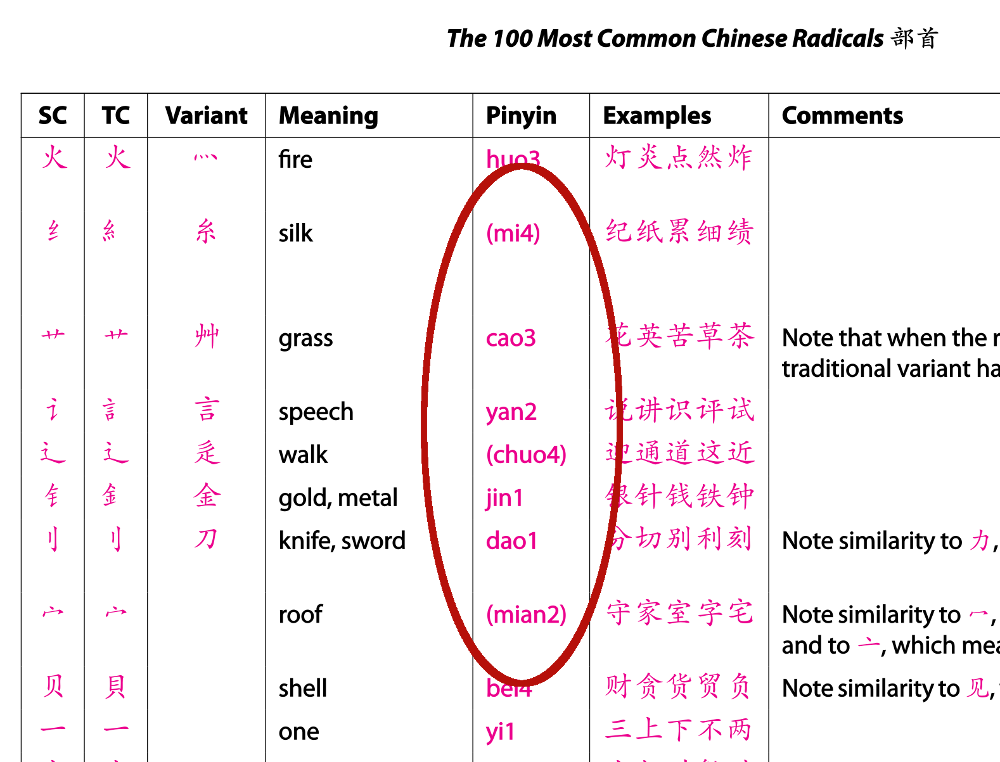

The reason Kickstart your Chinese character learning with the 100 most common radicals is so popular is that I took the time to look at only the most important ones, based only on the most common characters. This means that you can safely learn anything on that list and be sure that it will be useful either immediately or very soon. This is certainly not true if you learn all the 214 components that can serve as radicals.

Chinese characters with the same components but different radicals

Before we move to the question of pronunciation, let’s look at one final example that should illustrate why “radical” is not a very useful concept. Some characters have the same components but not the same radical. Here’s one example of that, fetched from my article about characters with the same components:

- 呆 (dāi) “dull, stupid” – the radical is 口

- 杏 (xìng) “almond; apricot” – the radical is 木

I hope it’s clear by now what the difference between a radical and a character component is. Let’s move on!

Chinese characters that share the same components but are still different

Should you learn the pronunciation of radicals?

It’s time to finally answer the original question: Should you learn the pronunciation of radicals? The reason I took so long to get here is that if you’ve followed my reasoning so far, you already know the answer.

If you used the word “radical” correctly when asking the question, the answer is “no”, just like the answer to the question if you should learn radicals in general is also “no”.

However, there’s an additional reason that learning the pronunciation of radicals is less useful than learning their meaning. It has to do with what I said earlier about radicals often being semantic components. As I said, learning the meaning of radicals can be useful because they are also common semantic components.

The same is not true for pronunciation. Many of the radicals have strange pronunciations that even native speakers don’t use or even know. What’s the pronunciation of 辶? How about 宀, or 彳? The only reason you might want to know that is if you want to type them like I did now.

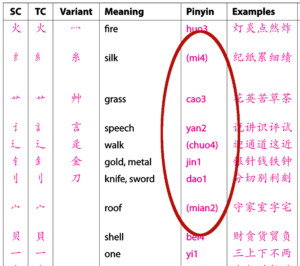

The radical of a character is rarely the phonetic component, so this information is also unhelpful when trying to learn compounds. Of course, some radicals are also common stand-alone characters like 人, 火 or 山, but since it can be hard to know which are useful to learn and which are not, I indicated pronunciation you can skip in brackets in my list:

Please note that these are the most commonly used radicals. If you look at a complete list sorted by number of strokes, a much larger amount will be useless in terms of how they are pronounced.

Whether or not you should learn the pronunciation of character components in general depends on what component it is. More than 80% of all Chinese characters are made up of a semantic (meaning) component and a phonetic (sound) component. Learning the pronunciation of common sound components is extremely important! If the component in question is not a common phonetic component, you should only learn it if it also works as a separate character as described above.

How native speakers talk about radicals without using their pronunciation

I said above that most native speakers don’t know how to pronounce many of the radicals. Try asking Chinese people how to pronounce 辶, 宀, or 彳 and you’ll see what I mean. You are very likely to be told their colloquial names, not how these characters are pronounced individually.

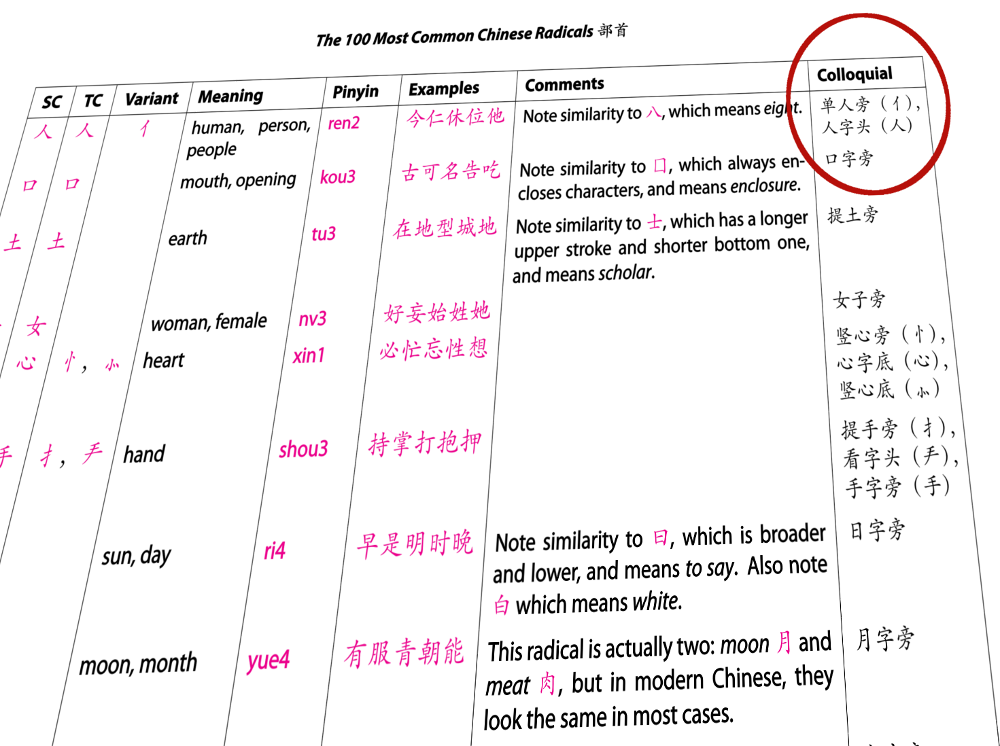

Here are the colloquial names:

- 辶 = 走之旁 (zǒuzhīpáng)

- 宀 = 宝盖头 (bǎogàitóu)

- 彳 = 双人旁 (shuāngrénpáng)

Learning these colloquial names is useful if you talk about handwriting with native speakers, such as if you want to ask someone how to write a character verbally. For beginners, this is overkill, but for intermediate and advanced learners who care about characters, you should learn the most common ones. Indeed, you probably know some without even trying, such as 三点水 for 氵 or 单人旁 for 亻.

Again, this information is included in my 100 most common radical list:

Conclusion: Radicals are not very useful for learners

Don’t learn the pronunciation of the radicals unless they are also common characters in their own right (in which case you will encounter them as such anyway).

Here’s a rule of thumb: if the pronunciation of the whole character is completely different from the character component you’re looking at, you can skip learning its pronunciation for now.

You probably still want to learn what it means, since this is the foundation of meaningful character learning in general, but unless it’s a common phonetic component, you don’t need to learn how it’s pronounced!

Editor’s note: This article, originally published in 2016, was rewritten from scratch and massively updated in June 2024.

Tips and tricks for how to learn Chinese directly in your inbox

I've been learning and teaching Chinese for more than a decade. My goal is to help you find a way of learning that works for you. Sign up to my newsletter for a 7-day crash course in how to learn, as well as weekly ideas for how to improve your learning!

13 comments

Thank you for this Olle.

Do you have any references on how to explain a character as a Chinese person would do it, using 走之旁 etc?

It’s partly improvised using parts people know for sure and making sure the other person thinks of the right character. So for example, if you want to describe 这, you could say something like: 走之旁加文化的文. Not sure if that was what you were after? There are no fixed ways of doing this, as long as the other person understands what you’re talking about, it’s okay.

“Not sure if that was what you were after?”

More or less. But I wondered if there might be a web site that gave a more complete list of terms such as 宝盖头 that I would otherwise not come across. Currently, when I try to remember a character I use my own English concepts, such as “roof like thing with tick on the top”. I thought it might be better to start using the typical Chinese way of describing the same thing.

You have a hundred of them in my kickstart list linked to in the article! This was partly based on a longer list for all radicals, but it seems to be unavailable now. If you find anything more complete, please let me know!

Isn’t the *entire point* of radicals deprecated? They were invented as section headings to enable lookup of characters in paper dictionaries. Certain character parts were arbitrarily selected as “radicals”.

Now that everyone uses computer dictionaries, the reason for radicals has passed and we can all concentrate on components instead.

Yes, I agree. This is what I wrote in the article too:

However, since students sill ask about radicals, I write about it. THe alternative would be that the same students find resources about radicals that are not at all adjusted for second language learners, which would be much worse.

Hi Olle,

I am considering making a list of phonetic components for my advanced students to study on Skritter. Do you A) know if there are any such lists already created on Skritter or B) think that would be a good use of time for advanced learners? I notice that after the summer, students have forgotten how to recognize and write many characters, so I’m trying to find some intelligent ways to help them. Thanks for any insights you have.

Best,

Jon

I wonder, what the sense of the pronunciation of a non character radical is. It’s like asking for the pronunciation of an i-dot. In your top 100 radical list I miss the information whether it is an own character or not.

This is indicated in the list already, as specified in the article, both in picture and text. The pronunciation written in parentheses can be safely ignored, meaning that they are either never or very rarely used as single characters.

Thank you so much for this article! I just started learning Mandarin and I’d like to learn characters as well as spoken Chinese, but I was admittedly a little stressed about memorizing the whole Kang Xi radical list. This gives me a MUCH better starting point; I finallly know what to focus on! Thank you for the excellent article, keep up the great work!

I wish I knew this before learning the tones and pronunciation for every single one of the 100 most common characters in the Skritter app. I looked through the menus and concluded it’s not possible to exclude those two types (tone and “reading”) from review for individual character flashcards.

Would be nice if the app had more options to curate what I want to review, i.e. custom labels and individual review type settings per character/word/expression. I know you only just had an episode on this, not fussing about flashcard learning too much 🙂

Hi Thomas! I agree that it would be great to be able to customise things more, and such features are coming to Skritter in the near future. However, I’m not sure it will be possible to fine-tune this on specific cards, but rather on the deck level, or maybe the deck section level. The problem is that this particular case is extremely specific. I mean, normally, you do want to learn the pronunciation of characters. Or if you don’t want to learn that, you can disable it entirely. But what I mean is that, assuming you want to learn the pronunciation of characters in general, there are very few cases where this wouldn’t hold true. You’ve found one of them here, but I’m hard-pressed to find other such examples!