Setting out on our Chinese-learning journeys, most of us feel positive about the language: the characters are beautiful and the sounds exotic!

Setting out on our Chinese-learning journeys, most of us feel positive about the language: the characters are beautiful and the sounds exotic!

Word formation is awesome: Isn’t it cool that “cinema” translates directly to “building of electric shadows” (电影院/電影院)? Or that “torpedo” is “fish thunder” (鱼雷/魚雷)? Okay, that’s not a beginner word, but you get my point.

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to this article:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcast, Overcast, Spotify and many more!

When the shine wears off

Few can maintain that pure, almost innocent attitude towards learning Chinese for years, though, and most of us feel frustrated or annoyed, at least some of the time.

Why, oh why, didn’t Chinese end up with a phonetic alphabet rather than a needlessly complex logographic writing system? And while tones are fun to learn, it can be seriously annoying when you hear no difference at all between what you said and the correction you received from a teacher.

Most of us oscillate back and forth along the attitude spectrum. I’m usually positive about learning and teaching Chinese, but I sometimes also feel frustrated when I mix up two characters with the same pronunciation, but with subtly different meanings.

Most of us oscillate back and forth along the attitude spectrum. I’m usually positive about learning and teaching Chinese, but I sometimes also feel frustrated when I mix up two characters with the same pronunciation, but with subtly different meanings.

But does it matter? Does a negative attitude towards learning Chinese mean that you will learn less?

Does a negative attitude make it harder to learn Chinese?

The research in this area is not clear cut, because there are so many factors to keep track of. What do we mean by “attitude”? Towards what language? Or maybe not towards the language, but towards the culture or society associated with the language? For which students? Children or adults? Under what circumstances? And so on.

The general idea that emerges is that attitude might not have a large impact on your ability to learn directly, but that it does have a significant impact indirectly. It’s not that your learning becomes more efficient, but that students with a positive attitude are more likely to expose themselves to the language and engage with it, which in turn certainly does lead to improved proficiency.

In general, how much you learn is influenced by how much time you spend, your learning method and what content you’re focusing on. There are of course other factors, but these are less interesting if you can’t do anything about them. For example, you can influence how much time you spend learning Chinese, but you can’t change your age.

Finding interesting and entertaining ways of learning Chinese is therefore not so much about squeezing as much as you can out of every hour, but more about increasing the total number of hours. You are far more likely to spend an hour a day reading if you enjoy it.

Naturally, if you dislike learning Chinese enough, you might quit entirely, if you don’t have any external factors forcing you to learn. I’m serious: having fun is important!

Chinese is fascinating and exciting, not weird and stupid

Deliberately adopting a positive attitude towards Chinese is not easy, but it can be done. A language is neither good or bad, it just is. Positive and negative come from the way you look at it.

Here are some examples of shifts in perspective that can help you adopt a positive attitude. All these are based on real complaints by students:

Characters are beautiful fragments of living history, as well as a playground for those interested in memory techniques and mnemonics. They are not unnecessary, so complex they can’t be learnt, nor simply a number you have to cram in before you can say that you know Chinese. Understanding characters is not only possible, but necessary to learn them effectively.

Characters are beautiful fragments of living history, as well as a playground for those interested in memory techniques and mnemonics. They are not unnecessary, so complex they can’t be learnt, nor simply a number you have to cram in before you can say that you know Chinese. Understanding characters is not only possible, but necessary to learn them effectively. Pronunciation opens up a rich world of sound you didn’t know existed before. Learning to hear and pronounce new sounds can take time, but is made easier by the regularity of the sounds and the fact that Mandarin has very few of them. The sound system is not chaotic and tones are certainly not unnecessary additions to syllables. Pay attention to pronunciation from the start and it you’ll thank yourself later!

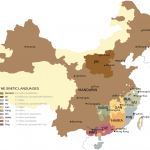

Pronunciation opens up a rich world of sound you didn’t know existed before. Learning to hear and pronounce new sounds can take time, but is made easier by the regularity of the sounds and the fact that Mandarin has very few of them. The sound system is not chaotic and tones are certainly not unnecessary additions to syllables. Pay attention to pronunciation from the start and it you’ll thank yourself later! Regional accents and other dialects offer broad and interesting variation. If you think standard Chinese isn’t enough, you can play around with endless regional accents, or even learn completely other dialects. Speaking with people from different places shows you different perspectives of Mandarin pronunciation, and a person with a non-standard accent does”t “talk weird”. If you’re interested in regionally accented Mandarin or pronunciation variation in general, no conversation, lecture or speech will ever be boring.

Regional accents and other dialects offer broad and interesting variation. If you think standard Chinese isn’t enough, you can play around with endless regional accents, or even learn completely other dialects. Speaking with people from different places shows you different perspectives of Mandarin pronunciation, and a person with a non-standard accent does”t “talk weird”. If you’re interested in regionally accented Mandarin or pronunciation variation in general, no conversation, lecture or speech will ever be boring.- Chinese culture and society is as diverse as any other, perhaps even more so than most, and there are innumerable examples of this to experience, and more people to get to know that you will have time for. Experiencing another culture can also help you understand your own. Chinese culture is probably quite different from your own, and with an open mind, you can learn a lot!

The examples above show different perspectives and aren’t attempts to say what’s actually true. The point is that instead of regarding something as a problem or an obstacle, you should try to look at it as a friend or a place you would like to get to know better and eventually understand and love.

Your native language is also weird and stupid sometimes

If you do encounter something you think is genuinely weird and stupid (it does happen), consider for a while that your language has lots of equally weird and stupid things that some foreigners don’t think highly of. Having learnt English as a second language myself, here are some examples of things that just don’t make sense (from Richard Lederer):

- A slim chance and a fat chance are the same; a wise man and a wise guy are opposites

- Overlook and oversee are opposites; quite a lot and quite a few are alike

- The weather is hot as hell one day and cold as hell the next

And let’s not discuss English spelling!

Or grammar for that matter. Imagine learning English as a native speaker of Chinese. There are so many things you suddenly need to care about that are so easy in Chinese! What’s the big deal with articles? Why do you have to inflect verbs so much? Why bother with plurals?

And, in particular, why is there so much redundancy? We know that the sentence “she likes red” is third person singular without inflecting the verb (it says “she” right there at the start). And while we’re at it, why make a fuss about “she” and “he” anyway, why not just “tā”?

Okay, sorry, got a bit carried away there. The bottom line is that it’s meaningless to point at another language, and say “haha, look, how stupid that is!”

Explore and learn; savour the differences.

Ask basic questions, but don’t question the basics

Asking many questions to verify what you know or to gain new knowledge is a natural part of learning, but contrary to what many teachers tell you, not all questions are good questions.

You should be particularly careful with “why” questions. In certain cases, the answer can make a lot of sense and teach you something useful. For example, if you observe something that seems inconsistent, such as the third tone being pronounced differently in different situations, there probably is a good answer to the why question.

You should be particularly careful with “why” questions. In certain cases, the answer can make a lot of sense and teach you something useful. For example, if you observe something that seems inconsistent, such as the third tone being pronounced differently in different situations, there probably is a good answer to the why question.

However, “why” questions from students are often born out of frustration rather than curiosity. Questions like:

- Why are there so many difficult characters?

- Why don’t they use tenses like we do?

- Why don’t the Chinese use an alphabet like everybody else?

- Why are there so many synonyms for everything?

- Why are there tones in Mandarin?

These questions might be good for a thesis, but the answer (if there is one) isn’t likely to make the average student any wiser. To put it briefly: Ask basic questions, but don’t question the basics.

Conclusion

Learning Chinese takes a lot of time. With a positive attitude, it will be easier to invest both time and energy into the project. It will also help you deal with frustration, set-backs and problems you encounter along the way. It might not be easy to change your attitude towards Chinese language and culture deliberately, but even changing it slightly to the better can make a difference.

The goal in this article is not to hide the difficult aspects of learning Chines,e but rather to highlight that the language is what it is regardless what you think about it. With a positive attitude, you will at least enjoy the learning experience.

Editor’s note: This article, originally from 2010, was rewritten from scratch in April 2020.

Further reading

Dehbozorgi, E. (2012). Effects of attitude towards language learning and risk-taking on EFL student’s proficiency. International Journal of English Linguistics, 2(2), 41.

Masgoret, A. M., & Gardner, R. C. (2003). Attitudes, motivation, and second language learning: A meta‐analysis of studies conducted by Gardner and associates. Language learning, 53(S1), 167-210.

Yu, B. (2010). Learning Chinese abroad: The role of language attitudes and motivation in the adaptation of international students in China. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 31(3), 301-321.

Tips and tricks for how to learn Chinese directly in your inbox

I've been learning and teaching Chinese for more than a decade. My goal is to help you find a way of learning that works for you. Sign up to my newsletter for a 7-day crash course in how to learn, as well as weekly ideas for how to improve your learning!

24 comments

Chinese is definitely fascinating and beautiful and exciting. There is a weird and odd element to it but for me that’s part of the learning curve and what seemed weird at first quickly becomes beautiful once I understand the reasoning behind it. A possitive “can do” attitude will get you so much further with a lot less obstacles in your way! I love how I seldom hear my teacher say “that’s just the way it is” when we tackle something new, there is always something more behind it and it even makes grammar fun (something I’ve never been able to say about any language I’ve learnt).

I have learned some languages before, English since I was 8 years old, German for 5 years, Swedish for about 6 years and Latin for a couple of months. From those three languages English is the only one that I can speak today, others I’ve give up and forgot. I don’t have any passion for English but it allows me to do many things like watch my favourite TV shows without subtitles, read great books that aren’t translated to Finnish and so on.

But Chinese is different, that’s my real passion. Some could say my destiny was to learn Chinese because I’ve always been interested in it. It all started even before I was born because my parents were living Beijing when my mom was expecting me.

Online I’ve met other as passionate Chinese learners as my self and it’s great to see where their passion has led them.

On the other hand now when doing a bachelor degree in Chinese I noticed that some of my classmates study Chinese because their parents told them to do so, or because it’s beneficial for doing business, reasons that aren’t based on passion. I wouldn’t learn Chinese if it wasn’t my passion, I wouldn’t find the motivation to do so.

“… read great books that aren’t translated to Finnish and so on.”

Have you used Chinese to read anything great which hasn’t been translated into any European language? Discovering how much wonderful stuff there is to read in Chinese which is not available in any non-Asian language motivates me quite a bit 😉

While I am not motivated by Chinese itself per se – there are other languages that I think are more fascinating and I’m not studying them right now – Chinese is still quite interesting, and I have a bunch of cultural/social/practical reasons which made me pick Chinese. And I am definitely not studying Chinese because my parents told me to – they actually discouraged me (well, my mother at least) from learning foreign languages, and even arranged to have my foreign language class postponed for a year in high school. That now makes me quite sad, because it would have been nice to have started learning foreign languages earlier … on the other hand. when I did start studying foreign languages, it was definitely due to my own motivation, so it might have been better than having my interest in foreign languages prematurely crushed by early bad experiences.

“Have you used Chinese to read anything great which hasn’t been translated into any European language?”

Not yet, because my Chinese doesn’t quite yet allow me to read those books and enjoy them, meaning I would need to use way too much dictionary while reading. But it’s my goal to read as much in Chinese as I can, as I love reading in Finnish and English too. If you have some recommendations for great books, I’m happy to hear 🙂

I think it’s interesting that you would compare English and Chinese, in the example “I have two cars” or 我有两辆车。Wǒ yǒu liǎng liàng chē. But why reach for such a bad defense? Chinese classifiers are NOT the same as measure words (e.g. a bottle of wine).

Classifiers are a system of concord; they are ‘redundancy features’ built into a Noun Phrase (NP) to show that a series of constituents construct a single phrase. English, in the EXACT SAME EXAMPLE, uses such a “stupid” (but different) redundancy feature to show concord: two carS.

Why do we need a plural here? “Two” is already ‘plural’, so why add a plural suffix to “car”? In Hungarian, “cars” is autók (autó ‘car’ + /k/ ‘plural’) and “two cars” is két autó; they simply drop the plural, because it’s already obvious. Chinese (and Central Asian Turkic languages and the Tibeto-Burman languages, like Tibetan) do the same thing. They don’t repeat the plural. But they do show SEMANTIC concord.

Finally… Hi Sara! Love your website! See you in Canton in 7 months! By the way, wouldn’t you say that it was 缘分 to study Chinese? 😉 I think it was for me! (I find ‘fate’ and ‘destiny’ poor translations for ‘yuanfen’, as a) fate and destiny tend to have negative connotations in a culture informed by Christianity, and b) yuanfen has a stronger participatory feel in it, as it reflects the views of a culture informed by Buddhism.)

Jason Cullen

Your example is a better illustration of how this works in English and Chinese, but it’s not a very good example if the goal is to use something familiar to explain something foreign, which was the case here. I’m not making a linguistic comparison here, I’m trying to make Chinese look less strange. However, I do agree with you that it’s not an example of English being weird, so I have changed the text to reflect this and also included your point about plural “s” on “cars”.

I agree that the goal should be to make Chinese look less strange. However, I believe that is the goal of my examples, which is probably why you incorporated some of my ideas into your text.

The linguistic arguments were made to make a case; that doesn’t mean I think they should be incorporated into a lesson.

The fact is though you are confusing measure words, and every language of Eurasia (Indo-European, Finno-Ugric, Tibeto-Burman, Turkic, Sinitic, etc.) has these, with classifiers. They’re just not the same thing. When I say 一个人, there is nothing like a mass noun and a measure here. So if you’re teaching grammar, regardless of the language you’re teaching, it’s fine to dumb down the jargon for students (example: when I teach English grammar, I don’t say ‘swim swam swum’ is ‘bare infinitive/base form’, ‘preterite/simple past’ or ‘past/passive participle’; rather, I use V1, V2, V3, and it’s easier to communicate). But you have to be accurate, too, or really weird stuff can pop up later. There’s been some research on this, which unfortunately I cannot cite right now. I’ll just have to say “trust me” for now!

Best of luck.

I think I have a pretty good grasp of classifiers vs. measure words (we do have substantial grammar courses in this program after all). This article is actually quite old, though, so I can’t remember exactly why I chose to use “measure word” throughout, but I guess it’s probably because otherwise people would just be confused since most textbooks only use one word. If this article was actually about grammar, I would probably think this through a lot more carefully, but I’m not sure it would help in this case. It might of course also be due to sloppy thinking, but in either case, thanks for pointing this out!

Oh, thanks for the citation! 🙂

Never knew why, but I’ve had a grudge on the Chinese language since I was little. Yes, chinese might be interesting, but it wouldn’t be as interesting as what you would think.

You see, being a guy who lives in a multiracial country, you get to know a few languages and start comparing them and then you’ll usually pick one of them to be your favourite.

So, I’ve friends who chose chinese as their favourite language, while I too have friends who chose the English language. Some are in the middle with no regards as to what language they favour.

So being one of the guys who favoured English… I have nothing good to say about chinese, nor have I destructive opinions of it.

Languages are a part of life. Just like choosing your lover, Choose the languages that you like, even if it’s some other foreign one.

Never ever make fun of other languages until you know how to converse and use them.

Oh, I’m chinese by the way.

This is the only article mentioning measure words (or classifier). Some books recommend to learn nouns with their measure word. Sounds reasonable, but even most of this books don’t give the nouns with their measure words or they are only on a beginner level. I didn’t find an online list nouns with correct measure word, so I have to follow a role or find it in context. Do you now a source of such a list?

Is it even your recommendation to learn this pairs, or is it better to stick with ge 个 and the rules, until one knows better?

My girlfriend is Chinese (but incredibly good at English) but the one place she does mess up is uncountable nouns and I can never actually explain when to use either (she wants to refer to the shade in a forest as shades, listen to music vs musics, …). Learning Chinese has made me enjoy pointing out what stupid rules we have in English

It’s so true that every language can be weird and stupid sometimes! People start to understand that about their mother tongues too when they start learning foreign languages.

For those who is interested in learning more about how strange English could be sometimes, I highly recommend a book called “Crazy English” by Richard Lederer.

A couple citations:

“There is no egg in eggplant nor ham in hamburger; neither apple nor pine in pineapple. English muffins weren’t invented in England or French fries in France. Sweetmeats are candies while sweetbreads, which aren’t sweet, are meat.”

“How can a “slim chance” and a “fat chance” be the same, while a “wise man” and “wise guy” are opposites? How can overlook and oversee be opposites, while “quite a lot” and “quite a few” are alike? How can the weather be “hot as hell” one day and “cold as hell” another?”

I included this in the new, updated version of the article! 🙂

Thanks Olle, that was just the pep talk I needed. I was feeling so discouraged this week and my “shine” was plumb wore out. Thanks for reminding me of the things I find so interesting about trying to understand and remember Chinese characters.

“It’s not that your learning becomes more efficient, but that students with a positive attitude are more likely to expose themselves to the language and engage with it, which in turn certainly does lead to improved proficiency.” I strongly agree. I noticed that people who identify themselves with the culture at some level, tend to be more motivated on the long-term. I once taught someone who needed the language skills for his management job. He neither liked that job nor the company he worked for, he also had his problems with the culture that he associated with the language, so to no one’s suprise he started missing classes and never got very far.

I come from India. Trust me hindi, devnagri, bengali , marathi or any of the languages originated from Sanskrit is scientific, logical and makes complete sense. To know the complete language all you need to know is the alphabets and phonetics of albhabets, that is it, rest everything follows. There are not even pronunciation related mess like the English language.

The more you will know about the logical integrity of Sanskrit the more you get in awe of it. It is limitless.

There are so many things other important to do in life. I wonder why somebody has to stick to a languages which have no logical foundation (including English) and waste precious hours of life.

I understand that there is a legacy associated with a language. But it is equally important to understand the need of time, the age and language is an outcome of human consciousness. So language must evolve with time and it is imperative to get into choices if it leaves us to spend more time in other important things in life.

These are my personal views , not to be taken offensively.

no. my language does not have stupid things. a ton of homonymes homophones and the tones make chinesse stupid. Tones exist for showing emotional charge not changing the meaning of the word. You are strangled or got a cold? good luck communicating in chinesse or japanesse. I am romanian btw. Consider spoken chinesse is so hard chinesse people need subtitles.

The whole point is that all languages can be fascinating and exciting, or weird and stupid, depending on your perspective. You only think Romanian is reasonable because it’s your native language; Chinese people who learn Romanian surely have at least as many things to grip about, just like you do with tones in Mandarin.

For the record, there’s no reason to believe that Mandardin would harder to communicate in if you have a cold compared to other languages. And no, native speakers of Mandarin do not need subtitles to understand their own language on TV. There are many reasons news broadcasts typically have subtitles, but that’s not one of them. You have to remember that only a minority of Chinese people speak Mandarin as their first language.