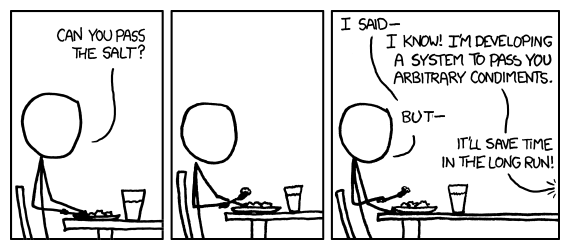

For some people, completing a certain task is not enough, it has to be done perfectly. Intuitively, I count myself to this group of perfectionists, but intellectually, I’ve gradually come to realise that this is a double-edged sword and that there are times (quite often, actually) when aiming for perfection is simply stupid. In this article, I will talk about some of the negative aspects of trying to get everything right too quickly. This article is not only for anyone who can at least partly recognise themselves in the xkcd strip below.

When perfectionism becomes an obstacle

I’m prepared to say that perfectionism is always bad if taken to extremes, with the possible exception of pronunciation. I really think that learning tones and sounds properly in the beginning is well worth the effort in a way that writing characters beautifully or perfectly is not. So why is perfectionism so bad? Because it is inefficient. Spending too much time on something might mean that you spend less time on widening your horizons and learning more, which would in the end lead to better results.

Let’s take an actual example. If I had a fairly big test next week, covering several chapters and many hundreds of new words, I’m tempted to aim for 100%. I did that all the time for the first year of Chinese, and sure, it paid off grade-wise, but I think that the price I paid was too high and today I would be much more careful.

Something is better than nothing

Another kind of negative perfectionism is the kind that stops you from doing anything at all (see the xkcd strip above). You don’t start reading because you haven’t found the perfect textbook, you don’t speak because you can’t pronounce all the sounds yet or perhaps you haven’t even started learning Chinese because you haven’t found the perfect system to use. Everything will be done in the future, but the truth is that you can’t do anything in the future, you can only do things in the present.

This is a sickness that can be found at all levels, from the very general and long-term to the fine details of daily language learning. Don’t do this. Studying something is always better than studying nothing. Or, put in another way, showing up is what really counts, not the imagined quality of practise you don’t get. Don’t aim to be perfect, start practising and you will see results after a while; you can worry about perfection later.

What’s the alternative to 100%?

The alternative would be to be satisfied with something like 85-95%, which indeed isn’t bad (this is the level most spaced repetition programs aim for, for instance, also with efficiency in mind). In my experience, reaching this level might require lots of work, but increasing the score further takes even more time per percentage point. To be sure to ace an exam, you really need to review a lot and you will end up reviewing things you really don’t need to review, just to make sure you know every single thing that might come on the exam. Making sure you have a good grasp of the material and then being a bit more relaxed and accepting the fact that you might forget minor parts on the exam takes significantly less time and energy.

Smart, not lazy

I think those of you who frequent this website know that I don’t advocate this approach because I’m lazy. The point here is that if the idea is to get really good at something (like Chinese) , focusing on knowing everything you learn until you know it perfectly is a waste of time. That time could be spent practising pronunciation, broadening vocabulary or reinforcing grammar. I’m sure this gives a lot more in return for the time invested. I don’t mean to say that a solid foundation isn’t important (see my comment about pronunciation above), but I’m saying that you won’t get very far if you spend years just laying the foundations. I’d much rather learn 100 words and remember 90%, than learn 50 words in the same time and remember every single one. I’d much rather be able to write 100 characters other people can understand than 10 people think are beautiful.

Naturally, scoring high on exams isn’t a bad thing. If you’re taking formal classes in Chinese, you might want to earn a good grade, in which case you have to partly ignore what I say here. A good result also gives a certain sense of achievement, which shouldn’t be neglected. However, I’m convinced that caring too much about grades is detrimental to learning, especially if we consider the fact that few courses are exactly matched to what you want to learn (especially if you study in East Asia, where ideas of what constitutes a good learning environment might differ greatly from your own preferences).

Some final words

I try to limit the areas I want to be perfect as much as I can; the only area I’m never satisfied with 90% is pronunciation. For other things I’m currently doing (like writing lots of articles in Chinese), I don’t want to understand 100% of all the mistakes I make, because that would take so much time I would never actually get down to writing the second, third and fourth article. I realise that not all learners will recognise this problem, but I hope those of you that do have found this article interesting.

Tips and tricks for how to learn Chinese directly in your inbox

I've been learning and teaching Chinese for more than a decade. My goal is to help you find a way of learning that works for you. Sign up to my newsletter for a 7-day crash course in how to learn, as well as weekly ideas for how to improve your learning!

14 comments

Being a perfectionist myself, this article has been a revelation. I certainly have stuff to work on, and your views have inspired me greatly, to say the least. Something IS better than nothing. Thank you

Interesting article. I fall into the perfectionist trap in that I always like to complete things 100%. This applies to everything I do in life, I always want to completely finish things. For example, if I’m reading over a chinese text, my goal is to learn every single new word, and make a note of every interesting sentence and grammer point. I do wonder whether I would be better off spending less time on the article, just picking out a few words, and then moving on. Or whether this thorough approach is actually the best way to go.

Whilst learning my second language, I settled for less than perfect in all areas with the one very clear exception of pronunciation. I gained more confidence by learning correct pronunciation at the start when there was, what seemed at the time, an almost insurmountable amount of work to do in other areas. I suppose I was doing what I knew I could do perfectly and then coping with the rest in a more pragmatic way.

I’m quite curious what your reasons may have been for striving to perfect your pronunciation from the very beginning.

I (personally) had two reasons to care about pronunciation: First, it’s the most skill-like part of learning a language and thus involves more habit-like processes than anything else. This means that it’s harder to change bad pronunciation later. Second, I think pronunciation is interesting. My research is in acquisition of second language phonology and pronunciation, which reflects the same interest. This interest isn’t limited to Chinese, though.

Great article. I’m exactly stuck in the phase “I don’t read cos I haven’t found the perfect book yet”, and this has opened my eyes!

I have a question: do you really believe that, being a non-native speaker, we can learn Mandarin Chinese to a 85-95% level?

I have learnt many other European languages, and was able to reach a very advanced level (by “advanced” I mean being able to read, listen, write and understand something more or less like a native speaker would). But I still have the feeling this will never happen with Mandarin Chinese.

I have been stuck in the ‘my foundations have to be perfect’ stage for over a year! I’ve suddenly realised how behind I am – this article has given me a whole new perspective!!!

This resonates with me in a large way and I have a personal epiphany story to share about it. One of my hobbies a few years ago was DDR and Taiwan’s proximity to Japan meant they have new machines earlier than America, making my study at 师大 extra enjoyable as I always had something to do in the night if none of my other friends suggested anything. I befriended a guy named Ethan and we went to eat (perfect fried rice place in Ximending, I wish I remember where exactly) and he asked how I usually go home. I started to say it and he interrupted: 你为什么不用中文?

Naturally, many people had replied to my Chinese attempts in English since 1) I had only 8 months of Chinese at the time so people who had studied English in school often had superior English communication skills and 2) They probably wanted a chance to speak English, and maybe felt it would be more friendly. Ethan raised a great point though. I’m there to learn, why be a tourist? (I read that article too, haha)

In truth, one of my teachers at my American university ran a sink or swim class, and I swam, but she had such a disappointed disposition every time anyone made a mistake. I think this was overdone, and by making mistakes in Taiwan and afterwards (For example, I told the mayor of Kunshan: 我学了两个半年的中文了 last year and the smile that broke out told me I had made a mistake) I learn so much more. I managed to skip two semesters of Chinese because of my 2 months of study in Taiwan as I studied and applied what I learned in real life, and still felt I spoke much better than previously same-level classmates who had done intensive study in a class in Beijing for that summer. I think comfort zone should be among the first things to eliminate in language learning.