There’s a lot of talk about fluency in the online world of language learning. What does it mean to be fluent? What’s the best way to become fluent in a language? How fast can you get there? I find these questions interesting and I have discussed them before, but today I’m going to talk about another word that carries even more punch: mastery.

There’s a lot of talk about fluency in the online world of language learning. What does it mean to be fluent? What’s the best way to become fluent in a language? How fast can you get there? I find these questions interesting and I have discussed them before, but today I’m going to talk about another word that carries even more punch: mastery.

In my opinion, fluency simply means that you can communicate more or less without hitches, it says nothing about a deeper understanding of the language. Mastery, on the other hand, isn’t something superficial and it’s something that takes many, many years to achieve, even with full-time studying and the best of methods. I know many people would be content with just being fluent, but bear with me, I do think that what I have to say about mastery is applicable to fluency as well, it is one stop along the way to mastery after all.

What does it mean to master Chinese?

Again, to avoid this article being mainly about definitions of words, I will just state that in my opinion, mastery is what educated native speakers have of their native language. Thus, mastery doesn’t imply that you know everything (no one does), but it does mean that you have a really good grasp of the basics plus extensive knowledge about the language as it appears in speech and print today.

Can we reach such a level as second language learners? I think so, even though it will always be hard to match the intuitive feel for colloquial language that native speakers have, as well as the more emotional and associative side of words. I think we can reach clear and relatively accent-free pronunciation, but truly mastering intonation and tones is really hard. That doesn’t bother me, though, I think we can come close enough. According to this definition of mastery, I have mastered English as a second language, even though that’s of course easier than Chinese because of the linguistic distance to Chinese.

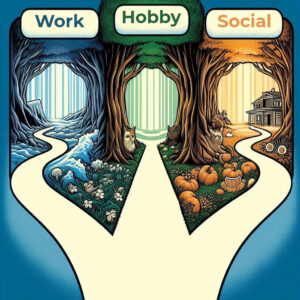

Three roads to mastering Chinese

Below, I’m going to argue that there are only three roads to mastering Chinese. This might sound like a very small number, shouldn’t there be many different ways? I don’t think so. The important thing to understand is that mastery requires a truly massive time investment, far exceeding a normal university degree or the ten thousand hours Malcolm Gladwell talks about. This being the case, we need to have a very strong motivation to keep spending time with Chinese. I have only come up with three different ways of achieving this, but if you can think of something else, feel free to leave a comment!

Road to mastering Chinese #1: Using Chinese in your job

If Chinese is an integral part of your job and you encounter different native speakers daily, you are sure to learn a ton of Chinese. Naturally, you will learn more if you focus on studying a bit on the side, too, but the exposure and amount of practice you will get will accumulate over the years even if you don’t study. Most people spend perhaps one-third of their time either working or on work-related things, so if this involves Chinese, you will get to 10,000 hours and beyond in no time.

My case is a bit special here since I will probably end up working a lot with the Chinese language, but not necessarily working with Chinese people or using Chinese as the operational language. For instance, if I write articles like this one, I don’t learn any Chinese at all. Still, teaching is a very powerful way of learning. I learn a lot from student questions and my own studying is also largely guided by what I feel is difficult to explain. Teaching Chinese is a good way of learning Chinese, especially if you have Chinese colleagues!

Road to mastering Chinese #2: Cultivating a genuine interest

Some people spend more time on their hobbies than they do on their jobs. If you can make Chinese the target of such a strong interest, you’re likely to be able to reach mastery sooner or later. This will power all kinds of useful processes, such as turning most of your life into Chinese. Instead of listening to Western music, you listen to Chinese music. Instead of reading books in English, you read everything in Chinese. You might also move to China, but this isn’t necessary (more about this later). With a moderately strong interest, you can get pretty far, but you need a genuinely strong motivation to reach mastery.

I qualify only partly. I don’t think Chinese is the most interesting thing on the planet and there are many other things I also like (gymnastics, writing and reading fiction, Rubik’s cube, etc.). Still, I have a tendency to be really interested in something for a few years and then switch focus. Chinese is so far the only exception. I have studied for about seven years now and even though I’m of course less enthusiastic than during my first semester, I still think Chinese is fascinating!

Road to mastering Chinese #3: Having your social life in Chinese

In the draft of this article, this third and last road to mastery was called “marry a Chinese-speaking man or woman”, but I found that to be a bit too narrow. The point here is that a majority of your social interactions need to be in Chinese and for many people, this means marrying a Chinese-speaking person, but it is of course conceivable that you could achieve the same by only having Chinese-speaking friends. Naturally, simply having someone who speaks Chinese around doesn’t mean anything, of course, you need to speak Chinese as well. This gives you the opportunity of really learning the spoken language, but probably does little for your reading and writing.

Even though I’m not married, I’m still doing pretty well in this area. My girlfriend is from Beijing and most of the people I speak with (apart from her) are Taiwanese. After moving back to Sweden, I will probably have fewer Chinese-speaking friends, but I still think a significant amount of my social life will be in Chinese. To truly reach a high level this way, one probably needs to live in a Chinese-speaking environment, though.

You don’t have to live in China

I have argued elsewhere that living in China is overrated and that you can equally learn Chinese at home (at least in theory) and this is true for mastery as well. Of course, many things will be a lot easier if you live in China, such as marrying a Chinese person, working with Chinese or maintaining a strong interest in the language. Many of these things might happen automatically, but if you’re not living in China, you will have to make an effort. Still, it’s a matter of different degrees of difficulty, not a matter of possible or impossible.

Different roads, different destinations

It should be obvious from the above discussion that mastery is a pretty broad term and that it incorporates a lot of different skills. The roads I have talked about in this article aren’t equal when it comes to these skills. For instance, a strong interest is probably the only thing that will make you fully literate in Chinese and what kind of job you have in Chinese matters greatly. For instance, compare my situation with someone who works with interpretation.

Still, I think it helps to think about different roads to mastery. It’s not the case that you have to choose one of them or that you can’t reach your goal if you miss some component, the goal here is to show that since we need to spend so much time, we’d better find ways of doing it that really matter to us and that make Chinese an integral part of our lives, not just something we study.

I love you, but sorry, you speak the wrong language

It’s also the case that we have different amounts of control over our choice of path. Most people, me included, certainly don’t choose their partners based on the language they speak (“Sorry, I do love you, but you speak the wrong language, bye!”) We have more control over what we work with, where we live and whom we choose to hang out with, but that’s still dependent on many other factors. Finally, even though we can cultivate and maintain a strong interest in the language, it’s hard to create one from nothing or control what we feel about studying Chinese.

That being said, we can make an effort to try to find the way towards mastery that suits us. I don’t know if I will ever reach a level of Chinese comparable to my English (or the English I knew when I graduated from university), but I’ll be sure to do my best and keep you updated about the process!

Tips and tricks for how to learn Chinese directly in your inbox

I've been learning and teaching Chinese for more than a decade. My goal is to help you find a way of learning that works for you. Sign up to my newsletter for a 7-day crash course in how to learn, as well as weekly ideas for how to improve your learning!

10 comments

Olle,

I really think you should write an article on the mystery of getting better at a language. My greatest improvements have come from moments when I wasn’t trying to go through an SRS deck, or use skritter, or study textbooks, or even going to classes. My greatest improvements came when I was just communicating with native speakers with no intent to learn anything. This happened both when I was in Taiwan and now that I have been in the US for five years. There is something that happens when you let go of “trying” and just embrace the chance to get to know another human being. All the vocabulary and reading and writing seems insignificant to exchanging meaning beyond concepts and words. This is when true mastery happens, I believe.

First of all, I would rather say getting a ‘native-like’ accent rather than becoming ‘accent-free’. Nobody is accent free – if people were accent free, how could I tell the Taiwanese tourists apart from the (northern) Chinese tourists in Japan as soon as they start talking? My English is not accent-free – my accent is Bay Area with an Appalachian flair and overenunciation due to being in Asia for years. I realize this is a nit-pick … but I think the concept of ‘accent-free’ is an obstacle to picking up a native-like accent – for example, if you want to sound like a native, you have to pick at least one native accent to study, which means you have to be aware that accents are not neutral.

Overall, I think this is a great article. I find it difficult to talk about fluency, and I think the distinction between fluency and mastery helps.

I think that, considering my ongoing interest in Chinese books, I will get mastery of reading eventually. However, I think I will get to mastery of writing never, and mastery of conversation only if I get a certain job/kind of social life.

And thank you for saying ‘having your social life in Chinese’ rather than ‘marry a Chinese speaker’. As an aromatic asexual, I really appreciate the inclusion of a diverse range of social lifestyles.

Oh, I meant “accent free” as in “not having a foreign accent”, I don’t think much of what I write applies to native speakers. So, yeah, of course you’re right, I just took that part for granted! 🙂

I second this great piece of article!!! As a language learner of English and Japanese for over the past 18 years (18 years so far for English, 10 years or so for Japanese), I say these are the “right ways” or mindset for achieving fluency, or mastery as all of the language learners dream of.

Mastery is a challenge, and very likely a lifelong challenge, but it is also a possible achievement that worthy of one’s time and effort.

天下無難事,只怕有心人。I wanna be the 有心人 in terms of language learning!!

Hi Olle, I’d be interested to hear more about this:

“I have a tendency to be really interested in something for a few years and then switch focus. Chinese is so far the only exception.”

I can definitely relate to switching interests every couple years. With Chinese, did the interest just stay naturally, or did you have to work to stay interested? Why do you think Chinese has held your interest, and not other pursuits?

Thanks, love your writing!

Hi Paul,

That’s a very good question. I guess part of the reason is that Chinese is more complex and more varied than many other hobbies I’ve had. There’s simply more things you can do and in more different ways. In fact, you can do anything with a language. I think the reason I’ve been into gymnastics for more than a few years now is similar, it’s simply a more complex/complete sport than diving, unicycling, swimming etc.

/Olle

I think the most interesting thing about mastery is that it ins’t a big deal at all, you listen Chinese, there’s Chinese in your PC,in your games,in our browser, in the bookshelf, in your brain, in your thoughts, your’re holding Chinese, and also wearing it. And then after the earth spinning around sometimes you mastered it. And that’s what every human being is doing right now, in our case, we just picked up another language do to it.

This reminds me of a post of a Chinese learner that seemed very deep, he said that he had always saw his Chinese media as means to acquire the language, he never let it flow, let it BE, forget that Chinese exists, forget about all the “language learning” stuff and see and hear the things he wants to without wanting to learn anything, let himself be Chinese. He stated that this thing, most than hanzis or tones, are what separate the natural speakers from the eternal learners.

I could instantly relates what he said with my experience learning English and it made me really rethink the way I looked at Japanese. I now think that’s a 道 in getting used to languages, it’s probably the so called “momentum” and when I looked back I realized I had almost no momentum with Japanese but with English it was every freaking day! I went to see blog’s like this, wikipedia and videos not because I cared to English but because those posts and ideas makes me excited and I can relate them to my life.

I had to laugh when I read your suggestion to marry someone Chinese as a way of learning the language. I’ve been married to a Chinese man for 30+ years and he will not speak Chinese with me. However, I have the opportunity to talk to his relatives, who speak little or no Chinese. Right now I am ramping up my Chinese learning because we’re planning a long road trip in China and I don’t want all the communication burden to be on my husband. Thanks for your interesting articles on this website!

Yeah, having a Chinese-speaking partner is of course no guarantee, it all depends on what language you speak. This article is more about discussing possibilities, but neither of these guarantee success in any way. However, I believe that you need at least one of them.