Learning things by heart used to be a mainstay of language education but is now often frowned upon. Approaches to learning and teaching languages change, but could it be that the pendulum has swung too far this time? Could it be that memorising things so you can recite them is good for learning Chinese?

Learning things by heart used to be a mainstay of language education but is now often frowned upon. Approaches to learning and teaching languages change, but could it be that the pendulum has swung too far this time? Could it be that memorising things so you can recite them is good for learning Chinese?

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcast, Overcast, Spotify, YouTube and many other platforms!

Learning languages by heart in Sweden and China

When I learnt languages in school, we didn’t have to learn hardly anything at all by heart. The Swedish curriculum is modern in the sense that it emphasises communicative competence over theoretical knowledge. You typically don’t need to quote the textbook, give verbatim definitions of words or recite grammar rules, but you do need to be able to use the language.

This is not true everywhere, though, and China can serve as a good counter-example here. Students are often required to learn long passages by heart in many different subjects, including languages. This might be a famous text (particularly in Chinese) or simply something important in the textbook (in foreign languages). When studying language and literature at higher levels, memorising target language texts is not uncommon.

Testing language ability or specific instances of the language

Learning a target language passage by heart is clearly about language learning, but let’s clarify the difference between the approaches here by looking at how learning outcomes are assessed. When learning by heart is in focus, advanced proficiency in the language is not enough to pass; you also need to know the exact content. In other words, a native speaker of English would perform badly on many English exams in China.

This can happen when learning Chinese with very old-fashioned teachers as well, who use fill-in-the-gap sentences on exams, but only accept the exact word that was in that sentence in the textbook, not any word that makes sense and fits in the gap. I’ve even encountered teachers who deduct points for forgetting the size of an object in a text, so if you write that the house is eleven metres wide, you get a point, but if you don’t remember the number and write twelve instead, you don’t.

Is learning things by heart good for learning Chinese?

In my opinion, if language proficiency is the goal, it makes sense to construct courses and exams in a way that tests this. Students who can recite the textbook but are otherwise unable to use the language should not get good grades, and students who can use the language but haven’t memorised the details of the text should do well.

So far so good, but why am I writing this article, then? Isn’t it obvious that learning things by heart is not the way to go?

Not necessarily. My opinion on the role of learning by heart has changed over the years. When I started learning Chinese at university, I thought that committing large chunks of language to memory was something boring, old-fashioned and ineffective. Why try to remember something exactly as it was said or written? It seemed like a meaningless waste of effort for little gains.

Fifteen years later, I’ve changed my mind. I think learning things by heart can be useful for learning languages in general and Chinese in particular, and that many modern approaches to language learning might have thrown out the baby with the bathwater.

Should we go back to memorising famous texts in the target language and memorise vocabulary meanings and grammar rules by heart? Should we test students on whether they remember how big a house was in a language exam?

No!

Can it be beneficial to learn some things in Chinese by heart so you can recite them verbatim?

Yes!

Learning by heart, remembering and memorising

When I say “learning by heart”, I mean memorising something in such a way that you could recite it verbatim. It’s also implied that this process refers to committing longer chunks of language, so learning that 一 means “one” and is pronounced yī is not an example of learning something by heart, but learning a sentence with this character in it so you could recite it later would count.

Here are some examples of things students sometimes memorise when learning languages:

- Memorising the exact definition of a word

- Memorising a collocation (combination of words that occur together frequently)

- Memrosinging a phrase or sentence

- Memorising a grammar rule

- Memorising a longer text or dialogue

Some of these activities are useful others are not. Learning by heart is in itself not good or bad; it depends on what you’re trying to learn and why.

As long as it’s in Chinese it’s okay to learn it by heart

A general rule of thumb is that it can be worthwhile to learn anything by heart as long as it’s in Chinese. On the contrary, memorising anything in English is of questionable value and something I would advise against doing. This would rule out examples 1 and 5 in the list above, assuming that the vocabulary definition and the grammar rule are in English.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that you should start memorising everything you encounter in Chinese, however, because the goal is to learn the language system, not specific instances of it.

Let’s look at some cases where I think learning larger chunks in Chinese can be helpful:

Memorising a phrase to learn a sentence pattern – Sentence patterns are abstract, and learning abstract things is harder than learning concrete things. Instead of trying to memorise something like 即使A,也B, memorise a real sentence like 即使明天下雨,我们也要去. This illustrates well how this pattern is used, and will also help you apply it in real life. This is not enough, but it’s better than having a flashcard with 即使A,也B. Read more about learning grammar in this guest post by John Pasden: How to Approach Chinese Grammar

Memorising a phrase to learn a sentence pattern – Sentence patterns are abstract, and learning abstract things is harder than learning concrete things. Instead of trying to memorise something like 即使A,也B, memorise a real sentence like 即使明天下雨,我们也要去. This illustrates well how this pattern is used, and will also help you apply it in real life. This is not enough, but it’s better than having a flashcard with 即使A,也B. Read more about learning grammar in this guest post by John Pasden: How to Approach Chinese Grammar Memorising a phrase to remember how a tricky word is used – Some words in Chinese have non-obvious usages. Sure, 桌子 is used in a similar way to “table”, but a word like 奇怪 in Chinese can mean both “strange”, which is the first usage you come across, but also “to think that something is strange”. To remember the second usage, you can memorise a short sentence like 我很奇怪你不帮你妈. For more about focusing on words or phrases, check Should you focus on learning Chinese words or phrases?

Memorising a phrase to remember how a tricky word is used – Some words in Chinese have non-obvious usages. Sure, 桌子 is used in a similar way to “table”, but a word like 奇怪 in Chinese can mean both “strange”, which is the first usage you come across, but also “to think that something is strange”. To remember the second usage, you can memorise a short sentence like 我很奇怪你不帮你妈. For more about focusing on words or phrases, check Should you focus on learning Chinese words or phrases? Memorising a phrase to learn a 成语 (chéngyǔ) or other idiomatic expressions – In most cases when learning the basic meanings of words, you can focus on just the word itself, and you you will then learn how the word is used by reading and listening. When it comes to chéngyǔ, the usage is almost always more narrow than you think, so the best way to learn them is to also learn an example sentence. This is very similar to the previous bullet point about tricky words.

Memorising a phrase to learn a 成语 (chéngyǔ) or other idiomatic expressions – In most cases when learning the basic meanings of words, you can focus on just the word itself, and you you will then learn how the word is used by reading and listening. When it comes to chéngyǔ, the usage is almost always more narrow than you think, so the best way to learn them is to also learn an example sentence. This is very similar to the previous bullet point about tricky words. Memorising a phrase to remember the difference between two words – If you keep mixing up two words, you can try memorising a sentence that shows how they are different. For example, if you’re a beginner and forget when to use 二 and 两, memorise a sentence like 第二个教室有两个学生. Coming up with these for tricky words can be hard, though, so you might need help from a teacher. I’ve written more about how to deal with near-synonyms here, but beginners often do well in simply ignoring finer differences between words: Dealing with near-synonyms in Chinese as an independent learner

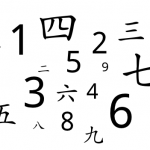

Memorising a phrase to remember the difference between two words – If you keep mixing up two words, you can try memorising a sentence that shows how they are different. For example, if you’re a beginner and forget when to use 二 and 两, memorise a sentence like 第二个教室有两个学生. Coming up with these for tricky words can be hard, though, so you might need help from a teacher. I’ve written more about how to deal with near-synonyms here, but beginners often do well in simply ignoring finer differences between words: Dealing with near-synonyms in Chinese as an independent learner Memorising an example of a large number to give it real meaning. Numbers bigger than a thousand can be tricky in Chinese, especially numbers above ten thousand. The reason is that Chinese changes words for every fourth zero you add (ten thousand, ten ten thousand, a hundred ten thousand, a thousand ten thousand), whereas English and many other languages change after every third (thousand, million, billion). By learning one good sentence for each, you anchor these abstract differences in reality. Check this article for actual examples and more about this: Do you really know how to count in Chinese?

Memorising an example of a large number to give it real meaning. Numbers bigger than a thousand can be tricky in Chinese, especially numbers above ten thousand. The reason is that Chinese changes words for every fourth zero you add (ten thousand, ten ten thousand, a hundred ten thousand, a thousand ten thousand), whereas English and many other languages change after every third (thousand, million, billion). By learning one good sentence for each, you anchor these abstract differences in reality. Check this article for actual examples and more about this: Do you really know how to count in Chinese? Memorising a longer passage, such as a song or poem, for cultural knowledge and access. Chinese people memorise a lot of passages from classical Chinese in school, and it’s not unusual for educated Chinese people to be able to quote poems and other famous works of literature. Replicating this as a foreign adult is hard, and not even desirable for most people, but it can be fun to do sometimes! For example, I once memorised half of 道德经 just to see what it was like. Naturally, if you learn something in modern Chinese by heart, you also get the words, collocations, grammar etc. for free.

Memorising a longer passage, such as a song or poem, for cultural knowledge and access. Chinese people memorise a lot of passages from classical Chinese in school, and it’s not unusual for educated Chinese people to be able to quote poems and other famous works of literature. Replicating this as a foreign adult is hard, and not even desirable for most people, but it can be fun to do sometimes! For example, I once memorised half of 道德经 just to see what it was like. Naturally, if you learn something in modern Chinese by heart, you also get the words, collocations, grammar etc. for free. Memorising song lyrics is easier but still useful. When it comes to music, memorising longer passages of Chinese is easy compared to written poetry or other forms of text, and if you like the music, it can be both enjoyable and relaxing to boot! I have been able to remember many words, phrases and collocations in Chinese many times because of the songs they appear in. If you like 一无所有 by 崔健, you’re extremely unlikely to forget this chéngyǔ ever again. Be mindful that music is an art form, so just like in poetry, language can sometimes be deliberately non-standard. I’ve written more about learning Chinese through music here: Why learning Chinese through music is underrated

Memorising song lyrics is easier but still useful. When it comes to music, memorising longer passages of Chinese is easy compared to written poetry or other forms of text, and if you like the music, it can be both enjoyable and relaxing to boot! I have been able to remember many words, phrases and collocations in Chinese many times because of the songs they appear in. If you like 一无所有 by 崔健, you’re extremely unlikely to forget this chéngyǔ ever again. Be mindful that music is an art form, so just like in poetry, language can sometimes be deliberately non-standard. I’ve written more about learning Chinese through music here: Why learning Chinese through music is underrated

How to memorise short and long passages in Chinese

Let’s wrap up this article by talking a little bit about how to memorise short and long passages in Chinese. If you’re like me and didn’t memorise long passages in school (in any language), this will not come naturally, but just like most other things in life, it’s a matter of practice. This could be the topic of a separate article, so let me know if you’d like me to write that!

There are two principles you should make use of:

- Active recall – You need to actively find the right answer in your memory for it to stick there. Ask yourself questions about the memorised passage, using cloze deletion or trying to recite it without looking at the answer. Just looking at the text is not a good idea.

- Spaced repetition – Spread out your reviews over time. If you want to remember it long-term (which is the goal here), you should avoid massing repetitions together. It’s much more efficient to review your passage once every other day for two weeks than seven times in a row, even if they both take the same amount of time to complete.

That’s it for now! What things do you find worth learning by heart? Do you even agree with me that memorising can be useful, or should we avoid it and focus on communicative learning instead? Leave a comment below!

Tips and tricks for how to learn Chinese directly in your inbox

I've been learning and teaching Chinese for more than a decade. My goal is to help you find a way of learning that works for you. Sign up to my newsletter for a 7-day crash course in how to learn, as well as weekly ideas for how to improve your learning!