This is a guest article by Julien Leyre of the Marco Polo Project. The publication of this article coincides with the start of this month’s translation challenge, so if you aren’t convinced that translation is a great tool for learning a language, this article is for you! Julien also shares many hands-on tips for making translations easier.

This is a guest article by Julien Leyre of the Marco Polo Project. The publication of this article coincides with the start of this month’s translation challenge, so if you aren’t convinced that translation is a great tool for learning a language, this article is for you! Julien also shares many hands-on tips for making translations easier.

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcast, Overcast, Spotify, YouTube and many other platforms!

How translation can help you learn Chinese

Remember? Once upon a time, translation used to be the main method for learning a foreign language. But then a new model came into fashion, called the ‘communicative approach’, promoting direct interactions in the target language. This makes sense: most of us are learning Chinese to communicate, not to become professional translators. So why should we bother practicing translation at all?

In preparation for the Hacking Chinese translation Challenge that starts today, this post will talk about translation as a way to learn Mandarin. Now, translating to and from your native language (or one you’re already expert at) are two very different exercises. In a previous post, Olle discussed the benefits of translation to Chinese. What I’ll talk about here is translating from Chinese into your native language.

Translation as active reading

At a very basic level, practicing translation (to your native language) will bring you the same benefits as reading: you will increase your vocabulary, reading speed, grammatical intuition, and overall comprehension. If the text is well chosen, you might even gain some cultural insights in the process.

OK – I get that. But why translate? Let’s put it this way: translation is a form of active reading. In one of his posts, Olle describes different ways to practice ‘listening’, from simple background listening to active engagement with the content. The same distinction applies to reading: you can be more or less active in your practice.

To see how this applies to translation, let’s go back to basics, and start with a definition. Translation consists of creating a piece of text in a target language (in our case, most probably English), which has the same meaning, structure and stylistic characteristics as a given piece in a source language (in our case, Chinese). To do that, not only do you have to read the source text, and make sure you understand all the words in it, but you must also look at difficult or ambiguous constructions, and make sure you clearly understand all of them.

Whether in the classroom or at home, we’re often satisfied with a superficial, rough, hazy understanding of what we read. Answering a teacher’s questions (or ticking the right HSK box), or even reading aloud, does not really test our deep understanding. We skim over sentences feeling that we got the gist. Translation provides a touchstone: once you’ve got to write an equivalent in your mother tongue, you can check whether you’re actually making sense of what you read – or not.

OK, sure – but I’m nowhere near that level yet, I’m still struggling with the basics. Should I just wait?

Any form of active learning takes energy, and I’m not saying you should spend all your learning time translating, especially if you’re still in early stages. But it doesn’t mean that translation is too hard for you now. In the rest of this post, I’d like to share a few tricks that will help you moderate the difficulty, and find ways of translating that are accessible to you right now.

Choosing the right text is certainly part of the question: how long it is, how intricate the language, whether it’s full of characters you don’t know, or whether it deals with a topic you’re familiar with – all these factors will impact your ability to translate. A word of warning though: I’ve seen many people go for ‘easy’ texts, because they seem more accessible. But there’s a big catch with practicing on ‘easy’ texts only, especially graded texts written explicitly for learners: it may quickly turn out to feel very pointless.

In 2011, I set up an organisation called Marco Polo Project, which proposes translation as a way to help people learn Chinese and understand China. The project was largely inspired by my own experience and frustrations as a language teacher and Mandarin learner. I started learning Chinese in 2008, and after three years, I got tired of the trite textbook. I wanted to discover fresh and authentic writing from China – but I didn’t know where to start.

Our website offers an original selection of new writing from China, and a simple interface to translate as you read. The idea was to bring great writing to learners – intermediate and advanced – encourage them to practice translation as they read, and share their translations with less advanced learners, so they could access these new voices from China in bilingual format.

This is what our translation interface looks like – with source text on the right, and a box to write your translation on the left. Check it out at www. marcopoloproject.org – registration is entirely free.

And in case you’re wondering, Marco Polo Project runs as a non-profit organisation. I hope to grow the community – but it’s not the whole point of me writing this post – there’s other ways you can practice translation. If you don’t want to do that on our website, I still encourage you warmly to exercise on a word document.

And in case you’re wondering, Marco Polo Project runs as a non-profit organisation. I hope to grow the community – but it’s not the whole point of me writing this post – there’s other ways you can practice translation. If you don’t want to do that on our website, I still encourage you warmly to exercise on a word document.

Pace yourself – be quick – and skip

I’ve taught translation at various universities. The first thing we tell students is that they absolutely have to carefully read the full text, make sure they understand all the details and really soak in the style, before starting to write their translation. Arguably, that’s how professional translators should work. But I’ll share a dirty secrete with you: that’s not what I’m going to recommend here. Quite the opposite.

If your Chinese is not perfect yet, carefully reading can take a very long time, and it can be frustrating, so frustrating actually that – unless there’s a deadline, or it’s a marked assignment, you’re more likely to give up. If your goal is to practice and learn, and if you’re not getting paid or assessed, then you should make sure the process is fast-paced enough that you get a sense of achievement and progress. There’s a simple way to do that. In my own translation practice, I always translate sentence by sentence as I go, I skip all the difficult passages deliberately – whole sentences and even entire paragraphs, and I always use google translate.

Google translate has very bad reputation, but if your reading skills are just so-so, it can be an amazing tool! It’s easy to use, it’s free, and it allows you to get the meaning of a text and sentence significantly faster and with significantly less effort than a dictionary. But you need to use it carefully. It’s often surprisingly accurate, and sometimes completely off the ball.

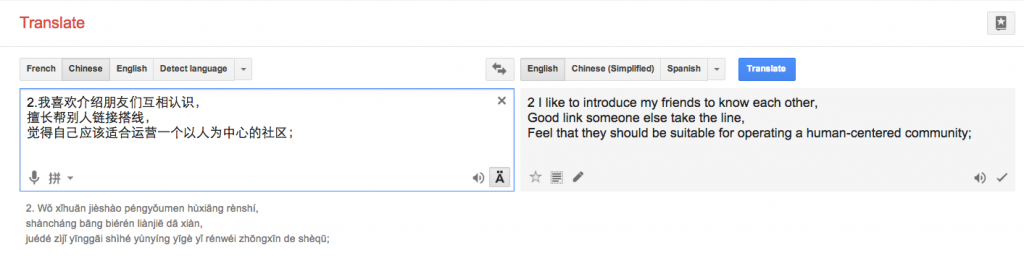

Concretely, this is how I would recommend you to use it. Pick a paragraph you want to translate, and paste it into the google translate box. Then split up the sentence by jumping lines after each full stop, for clarity. Look at the suggested translation, comparing it to the Chinese original. If a sentence sounds about right, copy-paste it into Marco Polo Project or your word document, or change a few words here and there to make it sound more idiomatic. You should be able to do that for about half the sentences in your text.

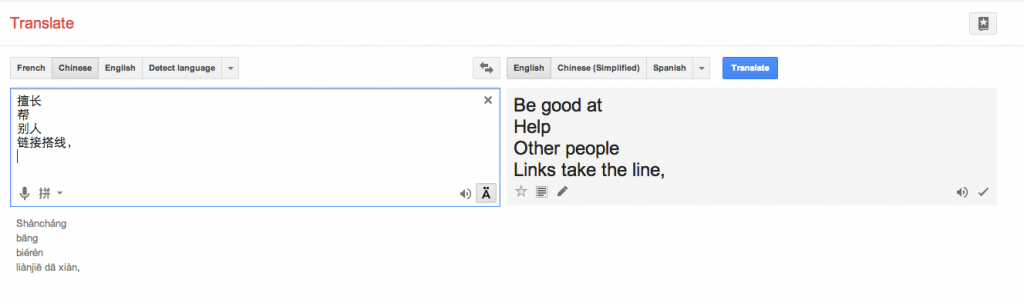

Half the time, however, something will be weird. When that’s the case, break up the sentence into parts by jumping lines after the main verbs, particles or connecting words. When you do that, the software will treat each component separately, and start working like a kind of predictive dictionary. Just break down the parts until you grasp the meaning. When you get it, put the parts back together in the right order, and write down your translation.

If it’s still too hard, just leave it aside until later.

Now, to be clear, I’m not saying this is how you should work if you want to be a professional or literary translator. This method will not give you the most thoughtful and elegant translation every time, but it’s quick, simple and satisfying. You don’t have to spend a lot of time searching for vocabulary or stretch your memory to remember what a character means. Half the time, the machine actually does an OK job for you the first time round. Getting that sense of satisfaction, and avoiding boredom or exhaustion, will be a serious advantage for long-term learning success!

Now, to be clear, I’m not saying this is how you should work if you want to be a professional or literary translator. This method will not give you the most thoughtful and elegant translation every time, but it’s quick, simple and satisfying. You don’t have to spend a lot of time searching for vocabulary or stretch your memory to remember what a character means. Half the time, the machine actually does an OK job for you the first time round. Getting that sense of satisfaction, and avoiding boredom or exhaustion, will be a serious advantage for long-term learning success!

Ready to go further? Try editing your translation

Fast-translation, following the method I described above, will help you go you through large quantities of text. But if you want take it a step further, editing your own translation (or someone else’s) is a great learning exercise.

This google-assisted ‘fast translation’ probably doesn’t read very well, it might be ambiguous, or even contain downright errors and inconsistencies. To start with, I’d suggest you review the translation line by line. Focus on word order, syntax and readability. Try to make your sentences simpler, more rhythmic – but always keeping an eye on the Chinese to check you’re not betraying the meaning. This exercise will double up as vocabulary review. It will teach you to better ‘skim’ over a Chinese text, and make you more familiar with connecting words or syntactic patterns.

As a second step, consider each paragraph as a whole (or even the full text if you’ve got the time), and focus on two particular areas:

- Tense and person: Chinese does not mark tense in the same way as English, and often omits subject pronouns. A common issue with translations will be that tense ‘jumps’ from past to present, or from ‘I’ to ‘they’ or ‘we’ without much consistency. Make sure this does not happen to you.

- Keywords: your text is likely to include a series of related words from a specific semantic field related to the topic. Check that they’re used consistently from paragraph to paragraph – but also, more importantly, check that the words in English actually mean the same as the Chinese words. To do this, you might check the keywords on a couple of online dictionaries, or even with a quick google search. It’s a great way to learn a few synonyms.

And if you want to take it even further, think of style and genre. Where does your source text come from? Is it standard language, or does it deviate from linguistic norms? When you’ve answered these questions, look for elegant, concise and apt equivalents that not only map the meaning of the source text, but also the style. This is a difficult and time-consuming pursuit, not always suitable for intermediate or even early advanced learners. But it’s also a fascinating and beautiful way to gain advanced understanding of the language. If you wish to really develop your reading skills, and appreciate subtle nuances of meaning and style in Chinese, this may be one of the best ways to go.

In conclusion: beyond target language communication, train your linguistic flexibility

There’s a final type of benefit that comes from practicing translation: it will make you more linguistically flexible.

Many language classes are held in the target language entirely, we think of ‘immersion’ as a great way to progress, and the capacity to ‘think in Mandarin’ is seen as a crucial step towards fluency. I’m not rejecting any of this upfront: creating a ‘Mandarin only’ mental environment does increase our capacity to interact with Mandarin speakers and Mandarin content at a reasonable speed.

However, our capacity to switch code from one language to another may suffer in the short term – and in certain contexts, this is a very precious skill. Have you ever found yourself in a situation where a concept only came to you in Mandarin, and you started wondering – what’s the word for ‘ganga’, ‘guanxi’ or ‘haixiu’? Outside the context of bilingual classroom, this hesitation may come in the way of clear expression.

As learners of Mandarin, it’s also very likely that we will find ourselves in a mediating position. As beginners, when travelling with friends who don’t speak the language at all, we do all sorts of minor translation – signs, directions, or basic polite interactions. As we reach intermediate and advanced levels, we’ll often have an opportunity to do minor translation tasks – what does this email/sign/article say? More importantly, when we spend significant amounts of time in a Chinese-speaking environment, we’re expected to report on our experiences to friends back home, family, colleagues and partners who do not speak the language.

For this, we must train our capacity to describe the values and world-views of Mandarin speakers in our own native language, and be comfortable shifting code. Translation is probably the best preparation for this task. Beyond practical, professional and social benefits, it will help us integrate all the complex emotional experiences we’ve had in a Chinese environment to the web of long-term emotional journey – and ensure some continuity between our pre-Mandarin selves, and the bizarre animals we’ve become since getting hooked on the language.

If you’d like to read more on this topic, I’ve written elsewhere about the role that translation played in my own intellectual development – and how it nurtures critical thinking, cross-cultural tolerance, and humility. So go check out this piece.

Converted yet? Try it for yourself, and see if translation works for you!

A note on my own background

I’m a French-Australian writer, educator and sinophile. I migrated from Paris to Melbourne in 2008, and I can probably count myself as perfectly fluent in both French and English today. I’ve taught languages and translation at various universities in France and Australia, studied many European languages, and reached various degrees of fluency among six of them – but Mandarin has been my biggest challenge by far.

I’d love to hear more about your experience of translation – don’t hesitate to send me a line at Julien@marcopoloproject.org

—

A big thanks to Julien for this article! I have mainly done translation in the other direction and hadn’t reflected too much about the importance of translating in the other direction, other than making sure that people understood texts read in class, so this article is most welcome to the collection here on Hacking Chinese.

Tips and tricks for how to learn Chinese directly in your inbox

I've been learning and teaching Chinese for more than a decade. My goal is to help you find a way of learning that works for you. Sign up to my newsletter for a 7-day crash course in how to learn, as well as weekly ideas for how to improve your learning!

5 comments

Grammatically, this may not serve you. But like all things, if you want the basics, you could try start from scratch. Building up the vocabulary is quite possibly the most important foundation you can lay before google translating your way to this new foreign world.

For that, there are plenty of help around with websites like mdbg.net and android apps like HSK Locker.

Get the fundamental words locked in place and from there reach out to newer words and slowly built up a gateway to the Chinese world.

I think with any language, translation is a huge help, building that base vocabulary is also key.

In my experience, the main benefit of translation has been to cement the vocabulary that I already knew, but only half. It takes time and multiple exposures to really remember a new word, and we often repeat the same searches again and again as we forget. Don’t know if that’s universal or just me – but that’s one of the things I really think translating helped me with.

I agree that translation is an excellent learning tool. There is no substitute for memorizing and knowing base vocabulary but translation helps you put those words into action. Seeing them in context and reading how they are used properly helps you to better understand and comprehend the language.

I’m fascinated with translation as a learning strategy, even though I’m a beginner and won’t be ready to tackle it for a while.

I know this originally ran 4 years ago but wanted to thank you again for this great article with so many tools, tips and thoughts and including this one at the end,

“Beyond practical, professional and social benefits, [translation] will help us integrate all the complex emotional experiences we’ve had in a Chinese environment to the web of long-term emotional journey – and ensure some continuity between our pre-Mandarin selves, and the bizarre animals we’ve become since getting hooked on the language.”