Much has been written about using spaced repetition programs such as Anki for learning many things, including language in general and Chinese in particular (see Skritter for example). Some are positive, saying that these programs have revolutionised the way they learn new words; others say that using them is a waste of time.

I place myself in the former category. I think that on average, spaced repetition software (SRS) can be a significant help for most learners, provided that you use them correctly and for the right things. Still, some people simply don’t like to use these programs, and it’s highly doubtful that forcing yourself to use them is beneficial. It should also be noted that these programs won’t teach you everything you need, even though that ought to be obvious.

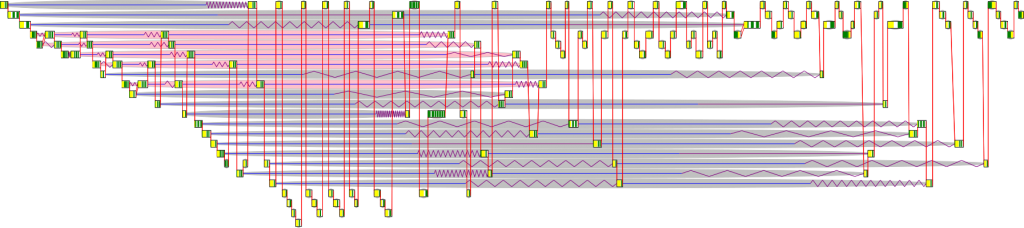

This graph is from Gradint, a program for creating spaced repetition audio on your own. Image by Silas S. Brown, official website at: http://ssb22.user.srcf.net/gradint/

Spaced repetition is not limited to flashcards

In this week’s article, I want to address a misconception that appears in questions I receive and discussions I read. Many learners think that spaced repetition is synonymous with spaced repetition software, which is wrong.

The first is an expression of the spacing effect, the second usually refers to flashcard programs that make use of this effect. You can debate whether these programs are the optimal solution to a given problem, but there’s little reason to question the spacing effect itself; it works.

For more about flashcards, see How to best use flashcards to learn Chinese:

The spacing effect

The spacing effect simply refers to the fact that humans (and indeed other animals) learn better if practice is spread out over time. This is not limited to language learning, but is a general phenomenon based on solid research. Since this blog is about learning languages in general and learning Chinese in particular, let’s stick with languages, though. For an overview of the science behind spaced repetition, check this site.

The indisputable fact, then, is that if you review (hear/listen/read/write) a word a large number of times in a row (massed repetition), you won’t remember it as well as if you take the same number of reviews and spread them out over time. Exactly how you schedule the reviews is a separate and much less important question; the main point is that you do it.

Spaced repetition without flashcards

So, if you don’t like Anki or Skritter, you should find some other way of making use of the spacing effect, because without it, acquiring a large vocabulary will be difficult. This article is not meant as a comprehensive overview of alternatives to spaced repetition software, but I will provide some examples to give you an idea of how you can learn vocabulary by relying on the spacing effect without using a flashcard app:

- Large amounts of extensive reading and listening (immersion) – This is probably the best way to acquire vocabulary. If you read and listen a lot to material at or below your current level, you will see the important words so many times that they will stick. Note that this is still spaced repetition! The difference is that in a novel, the words appear where they need to in the narrative, not according to an algorithm. It’s very rare that all occurrences of a word is massed together in one place, though.

- Goldlist method – This is a method for written language that has a very structured approach to spaced repetition, but which is completely analogue and considerably more relaxed than most flashcard programs. Put very briefly, it relies on periodically writing and manipulating/combining words in different lists, continuously refining and updating them. If you’re interested in how it works, check this video or check the creator’s website.

- Active reviewing of old material – Another way of making sure you don’t forget too much of what you learn is to regularly review the material you have studied until you know it really well. This includes keeping podcast episodes for months after you studied them, rereading old chapters in your textbook, going over conversations from last week and so on. As you can see, this is also spaced repetition, although in larger batches, which can feel tedious when you actually don’t need to review most of it, but need to go through everything because there might be important things you miss otherwise.

The reason spaced repetition programs are efficient is that they are convenient to use and that they keep track of what you need to review and when. If you’re in a full immersion setting as a beginner or intermediate learner, you probably don’t need this kind of scaffolding much, because hours and hours of studying and exposure everyday will work as a natural spaced repetition.

When exposure isn’t enough

However, most learners aren’t in a full immersion setting and don’t spend hours and hours every day studying Chinese. This mean that if you only rely on language naturally occurring in the material you read and listen to, this will be far from enough. In other words, the intervals will become so long that you forget what the word means between each occurrence.

For advanced learners, this is even more true. If you’re learning words you’re unlikely to encounter on a weekly or even monthly basis, just reading and listening won’t be enough. A reasonable question is of course why you would want to learn so rare words, but there are of course many situations where you might want to. For such situations, spaced repetition flashcard programs are great.

Spaced repetition is not limited to vocabulary either

Almost all discussions about spaced repetition and language learning focus on vocabulary. This is understandable, considering how big the task to learn tens of thousands of new words is, but it should be mentioned that the spacing effect is relevant for most skill-based activities too. While I haven’t seen any studies on these particular topics, it’s not unreasonable to assume that spreading out pronunciation practice, grammar drills and most other language learning activities will lead to better results than cramming all of them into short sessions. For a good overview of relevant studies of the spacing effect, please refer to this site.

Don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater

To conclude, even if you dislike flashcard programs, don’t dismiss spaced repetition in general. It’s a principle that holds true in almost all learning situations and can benefit your learning a lot. Most importantly, it can help you expand your vocabulary, but don’t forget that it can be applied to other areas as well.

Tips and tricks for how to learn Chinese directly in your inbox

I've been learning and teaching Chinese for more than a decade. My goal is to help you find a way of learning that works for you. Sign up to my newsletter for a 7-day crash course in how to learn, as well as weekly ideas for how to improve your learning!

5 comments

I think you are missing the power of context and meaningful content. Less repetitions of a word will be needed when inserted in the right context. When my Chinese friends correct me, or I’m reading something of interest to me, I just need 2-3 reps to stick the word in my long term memory. It will take 10 times more to memorize that same word using a SRS.

Yeah, good luck getting that kind of context on *every single word you ever study*. It would be nice. Some people are just much better at picking up language. Words just stick in their brain. Me, I need Anki to pound it into my thick skull one day at a time until it finally enters long-term memory.

Sure thing, both methods are complementary. For example, like you, I learned the fruits and vegetables by Anki brute force. Getting a job in a restaurant to learn this by context/exposure is something I couldn’t afford! On the other hand, I don’t believe in the “natural talent” to pick up languages. But that’s an entirely different discussion.

The Gradint URL has now changed to http://ssb22.user.srcf.net/gradint/ because the university permanently shut down the old server. Would it be possible for you to update the link in the article? Thanks.

Of course! The link has been updated. Thanks for reaching out and keep up the good work!