Grammar is something central to learning any language, including Chinese. If someone says otherwise, it’s probably because they don’t know what grammar means, so let’s start with a basic definition (from Wikipedia):

Grammar is something central to learning any language, including Chinese. If someone says otherwise, it’s probably because they don’t know what grammar means, so let’s start with a basic definition (from Wikipedia):

grammar is the set of structural rules governing the composition of clauses, phrases, and words in any given natural language

Thus, while it’s true that Chinese grammar is different from English grammar or the grammar of other European languages you might have encountered, Chinese certainly has a complex grammar itself and mastering how to make words, construct phrases and string together sentences is an essential part of learning Chinese. There’s little to disagree about here, so the big question is as usual not what, but how:

How should we learn Chinese grammar?

There are many, many different ways of approaching grammar, both from a theoretical point of view and from a practical, student perspective.

Even though the question above is very short, it covers a number of topics. For instance:

- Is there any difference between learning grammar when learning Chinese compared with other languages?

- What should students who are studying on their own focus on?

- What resources are available for learning grammar?

- Is it important to focus on grammar when learning Chinese or should it be done implicitly?

- Is theoretical knowledge useful, and if so, how should we acquire it?

There are of course many more things to talk about than these, but this serves as an introduction to the complexity of the question of how to learn grammar. Because this is such an interesting topic and there are so many different approaches, I decided to ask the expert panel and see what other language learners and teachers out there had to say about learning Chinese grammar. They have all answered the question in their own way, so rather than viewing this as a competition between different views on how to learn grammar, regard it as a tour through different available options.

Expert panel articles on Hacking Chinese

- Asking the experts: How to bridge the gap to real Chinese (immersion)

- Asking the experts: How to learn Chinese grammar (this article)

As you can see, this is the second expert panel article here and these articles are still very much an experiment. If you have suggestions or thoughts about the format or how to improve it, let me know! If you know someone who you think should participate next time or if you have ideas for different topics to ask, leave a comment!

Here are the participants in this expert panel on grammar. In order to scramble the order a bit compared with last time, I have sorted the answers based on the authors’ surnames (or family names) rather than their first/personal names:

- Imron Alston

- Greg Bell

- Yangyang Cheng

- Steven Daniels

- Ding Yi

- Carl Gene Fordham

- John Fotheringham

- Jacob Gill

- Hugh Grigg

- Ash Henson

- David Moser

- Alan Park

- John Pasden (separate article)

- Roddy

- Albert Wolfe

- Chinese Forums

—

Imron Alston has been learning Chinese since 2001, and in that time has spent a total of six years living, working and studying in China, mostly in Hebei and Beijing. He is an admin on the Chinese learning site Chinese-Forums.com, and is also the developer of a number of tools designed for Chinese learners, including Hanzi Grids – a tool for generating custom Chinese character worksheets, and Pinyinput – an IME for typing pinyin with tone marks.

For me, most of my learning was done through exposure to native speakers and native content, and while this also included following different parts of different text books at different times, I never really had a methodical approach to learning grammar. At times I also read various grammar books, and while it was nice reading them and having various structures explained, it’s never been something that has captured my interest.

Unfortunately what this meant is that as I got better at Chinese, I found myself at a stage I think of as ‘advanced with gaps’. The gaps continue to reduce the more advanced I get, but even now there are times when I find myself having a degree of uncertainty with whether what I’m saying is correct or not. It also means that except for basic things, I’m pretty useless at explaining grammar beyond ‘just because’. It’s quite possible that I would still be in this position if I had paid more attention to things like grammar, but in general I attribute these shortcoming to my lackadaisical study approach early on. For me, I was always more interested in being able to use the language, rather than in the study of the language itself, and looking back I think this hampered my learning to some degree.

If I were going about things again I’d certainly try to be more rigorous in this regard. I probably still wouldn’t dive deep in to grammar in the beginning, but I’d make sure to choose a good text-book series and make sure to work my way through it from start to finish. As a self-learner, the younger me was too concerned about becoming ‘advanced’ and saw using ‘advanced’ level text books and materials as evidence that I’d reached that position. What that meant was skipping past things that probably would have been quite helpful in solidifying my language skills.

I like to think my Chinese has turned out all right despite all of that, but it’s meant the journey has likely been longer than it otherwise might have been. My advice to new learners would be don’t try to rush things, and don’t get so caught up in just trying to use the language that you neglect skills that will help you improve. Keep working at things slowly and methodically, and you’ll set yourself up with a good base from which to continue your learning.

—

Greg Bell – I’ve currently got two blogs going on the matter, my language learning journey one at zhongruige.wordpress.

To me, the best way to learn Chinese grammar starts in the classroom or with a decent textbook that establishes a firm foundation in grammar. It doesn’t have to be anything complicated, but should at least set you right on the basics. Later on, though, I feel it’s best to switch over to material for native readers and just start reading. In my own experience, I’ve found the best way to learn grammar was not through complicated grammar guides, but instead just by reading as much as possible and across a variety of sources (novels, comics, nonfiction, etc.). After a while, I began to internalize the grammar, and started to gain a feeling for the language.

I don’t believe there is any real difference between learning Chinese grammar versus learning grammar for other languages. Although the lack of verb conjugation does make things easier, each language has its own nuances. Through either careful study or full immersion, I believe it’s possible to learn the grammar of any language.

If you’re studying on your own, I believe in the beginning something like AllSet’s Grammar Wiki is a fantastic place to start. When you’re comfortable with that grammar, you can move on to news articles, short stories, or even graded readers if they’re available. In the end, grammar doesn’t have to be too theoretical (sorry linguists!) and can naturally be picked up. As you advance though, it may be good to flip through some grammar books, ideally written for native speakers, and refine your understanding of the grammar of the language.

—

Yangyang Cheng is the founder and host of YoyoChinese.com, an online Chinese language education company that uses simple and clearly-explained videos to teach Chinese to English speakers. A previous TV show host and Chinese language professor, Yangyang is also one of the most popular online Chinese teachers with tens of millions of video views.

Why is learning Chinese grammar important?

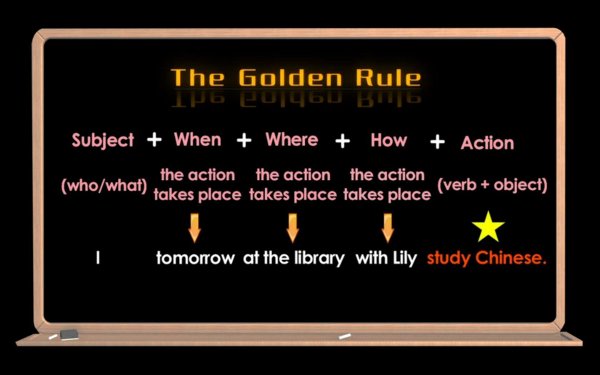

I often tell my students that learning a language is like building a house. Vocabulary words are like the bricks for your house and grammar is like the architectural blueprint that tells you how to put the bricks together and in what order. Learning grammar is important because it can give you the freedom to build correct sentences on your own. For example in Chinese, once you know the Golden Rule regarding Chinese word order, you’ll instantly know where to put time and location words and be able to speak with confidence.

When should I start learning Chinese grammar?

The best time to learn grammar is after you already have some basics down. For example, if you already have some decent vocabulary and some experience talking to a native speaker, your next step is going to be grammar.

Where and How should learn Chinese grammar?

We have 12 free gframmar videos on Youtube that you can watch. I also have a program on my Chinese learning site www.yoyochinese.com called “Yoyo Chinese Grammar”. Basically, you can think of this course as the video version of a comprehensive Chinese grammar book, but with lots of pictures/cartoons and clear and easy to follow explanations. The course is organized around different grammatical topics, such as “Chinese word order”, “Chinese negation words”, “how to form a Chinese question” and “how to use the notorious (ba3- 把)” etc. Each topic contains a series of mini lessons that build upon each other. You can either watch all the lessons in order to get a complete picture or skip around and only learn the things that you need.

—

Hi! I’m Steven Daniels, I’ve studied Chinese for years and lived in China even longer. My interests–learning Chinese, Chinese dictionaries, and programming–led me to create Lingomi and 3000 Hanzi.2 Tips for learning Chinese grammar on your own:1. Buy some material: most textbooks do a pretty good job of introducing grammar in each lesson. For-pay podcasts sites do a good job of this too. Don’t skip the grammar sections and examples, no matter how much you’d like to.

2. Add repetition: copy the grammatical patterns and examples out of your textbooks and put them onto flashcards. Review them like you’d review words or sentences.

Chinese Grammar is taught pretty well.

I’m often critical of standard practices for teaching Chinese, but grammar is one area where I’m not very critical. For those studying on their own, this is a quick rundown of how grammar is taught.

Currently, teachers provide beginners with a light introduction to basic grammar. You mostly learn simple sentence structures. At this stage, Chinese grammar feels pretty easy: in some ways it feels like Chinese barely has any grammar at all (especially compared to most other languages). At this stage, beginners, being confronted with tones and character, don’t have the time or the background to try and fully understand Chinese grammar.

Once a student gets to an intermediate level, they are introduced and re-introduced to Chinese grammar. At this point, Chinese grammar starts getting more difficult (e.g. the many ways to use 了 ). An intermediate student can learn most of the grammatical structures that Chinese uses, but these will still take a while to master.

When you look at advanced Chinese textbooks, there really isn’t a lot of grammar in the traditional sense. Advanced students spend time passively (or actively) reviewing grammar they learned at earlier stages. In addition, advanced students spend a lot of time learning collocations and trying to master when to use one of a variety of synonyms.

There are many different approaches that could be taken with teaching grammar, but they all have drawbacks. Using linguistics to introduce grammar could make learning it easier, but most Chinese learners don’t have a linguistics background. Trying to shoehorn more grammar in at earlier stages would require spending less time on pronunciation or characters — not a good tradeoff. Overall, I feel Chinese grammar is taught rather effectively. Of course, I do have a couple of issues.

- One possible complaint is textbooks tend to teach grammar once and expect you to master it. Luckily, most teachers will make sure you review it constantly. Like learning Characters, repetition is key.

- Finally, there aren’t any guides to reaching fluency. Going beyond advanced, students should learn how to go about writing different types of essays–how to structure their argument, how to use 连词 properly, etc. The old HSK’s writing section awarded students who knew how to structure essays in a way that native Chinese learners were accustomed to reading. If writing isn’t your thing, you can still learn these important structures and patterns by looking at Chinese debates online or joining a Chinese debate team.

—

Ding Yi is the Events Coordinator and full time teacher at Hutong School, the leading foreign owned Chinese language school in China founded in 2005. With an enthusiasm for teaching Chinese language and culture to students from all around the world, Ding Yi loves exchanging fresh ideas and making new friends along the way. He loves the airport, yuxiang rousi, and hiking.

Learning Chinese grammar is a step by step process. What I mean by this is that you must establish the foundations first and then build further on this. I therefore believe that absolute beginners must have a teacher.

Why? Since Chinese history and culture is immensely vast, evolution over time has meant that one character can hold a plethora of meanings – both literally and symbolically. Although Chinese sentences are more flexible in its word order compared to other languages, it is also very important, and so a difference in sentence structure or subtle addition of particles to the untrained ear is likely to cause confusion.

Another important aspect of Chinese is that it is an economical language; only a small number of words are used in order to express maximum power. An example of this is in the use of chengyu, which can be compared somewhat to idioms. Whilst they are often incomprehensible without explanation and seem to lack grammatical structure, these typically four character phrases give an insight into the complexity of the Chinese language.

To learn effectively and thus remember well, practicing speaking with a native speaker beside you is the best tool you can have, more so than learning the technicalities of the theory via a text book. A tried and tested method that I teach my students is to make long sentences when you first start learning the basic concepts of Chinese grammar. This will encourage you to keep to the correct order when attempting your own sentences in real life. All in all, in order to have a deep understanding of how grammar works, you must apply the practical usage in daily life, because actual application is the most important thing. In short, go out and practice speaking Chinese now.

—

Carl Gene Fordham is a NAATI-accredited Chinese-English translator with a Master’s degree in Translating and Interpreting Studies from RMIT University and a HSK 6 Certificate (the highest level Chinese proficiency certification). Carl currently runs a translating, interpreting and IELTS training school in Melbourne, Australia. He also writes a popular blog about translating and interpreting Chinese called 一步一个脚印.

In my opinion the best way to learn Chinese grammar is through a combination of reading textbooks and conversing with native speakers. Nowadays there are plenty of decent grammar textbooks on the market which can be very helpful, but the focus should always be on how to take what you learn in the book and apply it in real life. This is where the advice of a good teacher or tutor is essential, as the average native speaker friend will not be able to explain the finer points of grammar. But the learner should also take the initiative to put the grammar into practice too. As you start to do this, the grammar will become your own.

Personally I’ve found Chinese grammar to be, on the whole, a straight-forward system, much more logical than English grammar. It is, of course, also highly complex – that is, complex, but not necessarily complicated. The beginning and intermediate grammatical structures you pick up are powerful enough to be used in most situations – this is unlike other languages which require you to memorise large numbers of cases, tenses, genders, etc.

—

John Fotheringham is a serious “languaholic”, an adult-onset affliction for which he has yet to find a cure. John has spent most of the last decade learning and teaching foreign languages in Japan and Taiwan, and now shares what he’s learned along the way on his blog, Language Mastery | Tips, Tools & Tech to Learn Languages the Fun Way.

First of all, I would like to put to rest the ridiculous myth that “Chinese has no grammar”. Chinese may lack the verb conjugations so prevalent in Romance languages like Spanish and French, but that does not mean that the language lacks “grammar”. Like all languages, Chinese contains a finite (though gradually evolving) set of patterns, conventions, and syntactic rules that allow us to understand—and be understood by—others. Without grammar, languages would just be a chaotic slew of words and society as we know it could not exist.

However, just because grammar is essential for communication, it does not follow that one must spend heaps of time formally studying grammar rules to properly understand and form a language. As Barry Farber puts it:

“You do not have to know grammar to obey grammar.”

One’s ability to understand and form grammatical sentences is based on what’s called “procedural memory”, the brain’s way of storing and retrieving implicit knowledge. Without it, we would not be able to drive a car, throw a ball, or speak a language without consciously thinking through each and every tiny step, each and every time we do perform a complex action.

Many language learners fail to reach functional fluency in foreign languages because they approach language study as an academic subject, trying to force feed grammar rules into “declarative memory” (the kind of memory used to store explicit facts) instead of getting the input and output practice they need to truly internalize the language’s underlying structures. Procedural memories are only formed when you get tons of listening and speaking practice.

I will concede that a little bit of formal study can help prime the brain for the grammatical patterns it will encounter when listening and speaking a language, but this should augment—not replace—the active input and output activities that do most of the heavy neurological lifting. So take a peak at your textbook from time to time if you like, but make sure to spend the majority of your study time listening to Chinese podcasts, watching Chinese videos on FluentU.com, speaking with tutors on Skype, and chatting up native Chinese speakers at your favorite tea shop.

—

Jacob Gill is a graduate student at National Taiwan Normal University for Teaching Chinese as a Second Language. Co-Founder of Chinese Guild (add link), Chinese Teacher, Translator, Academic Advisor for Skritter, Summer Coordinator at Academic Explorers and blogger at iLearnMandarin. A Global Citizen, a life-long language learner and a full-time geek.

How should we learn Chinese grammar?

Chinese isn’t English, and it isn’t like many European languages, which means that a lot of the things we usually associate with grammar — tenses, conjugation, etc. don’t apply. If the rules we usually use have changed, we have to take the time to understand how the new rules work or interact with what we know, and how to build new connections where necessary. I like taking a more top-down approach to learning Chinese grammar, meaning paying attention to different word order patterns and how/ when they’re used, for example: simple Subject, Verb, Object, sentences, or the more complicated types: ex. subject, when, where, how, action. Ask yourself, how are these patterns similar to my native language, and how are they different?

By understanding the framework of Chinese grammar, patterns will begin to emerge and fall into place leading to quicker comprehension, and also the ability to produce your own sentences fast. Add context to various grammar patters, and when reading or listening in Chinese, try and pay attention to pre-set patterns, and how they’re used in conjunction with each other. In my eyes, people often learn best by doing something, so a key part of “learning” Chinese grammar is actually using the language to be understood. So start producing as quickly as possible, regardless of error!

Focus energy on how words work within, not independent of, grammatical chunks, ex. 因 為…所以…. I don’t think it hurts to spend a good deal of time memorizing these chucks, and basic Chinese Sentence Pattern books can be a great resource. One of the most successful programs I’ve ever studied in spent two hours a day drilling Chinese sentence patterns, and the results payed off in quicker overall comprehension and production all around. But, I think it’s always important to be thinking about ways to connect these new patterns to things you already know and understand. Relate them to conversations you’ve had, certain moods, or various situations, and then go out and use them. Grammar patterns will emerge naturally in conversation, and you’ll pick it up just as naturally if you force yourself to communicate and attempt to be understood. Challenge yourself to use new patterns, and to make mistakes. Ask for feedback, and if you don’t understand something, be sure to ask for help. Be creative, be fearless, and above all, use the language.

—

Hugh Grigg studied East Asian Studies at university, and is trying to keep up the learning habit long term. He writes about what he learns at eastasiastudent.net , to keep track of his progress and to try and help out other people where he can.

Despite running a website entirely devoted to Chinese grammar, I’m actually in the camp that says you shouldn’t spend too much time explicitly studying grammar. I think it’s important to have a reference available, to be able to ask questions, and most of all to be able to preview grammar points with explanation before you encounter them in the wild. Just as immunisation lets your body prepare to fight off an infection before it does the actual fighting, studying some grammar lets makes you more effective at doing the actual work of getting input and practicing (please forgive my love of terrible analogies). That’s the real work you need to do to learn a language: getting as much input as possible (reading and listening), and getting as much practice as possible (actually trying to speak and write as much as you can). Olle does a fine job of both writing about this and putting it into practice himself.

Our goal with our Chinese grammar site is to help out as much as we can with the process I describe here. We work as a pair (a native English speaker studying Chinese and a native Chinese speaker studying English) and try to explain grammar points as intuitively and simply as possible, but really focusing on giving plenty of natural example sentences. I use these sentences (and others) in the Anki SRS software and rehearse them that way, until the words, patterns and syntactic glue all become very familiar to me and are at my disposal in future. That’s how I study Chinese grammar and it’s the way I’d recommend (although I’m very much looking forward to reading the other responses here!).

I’ll also direct everyone who hasn’t seen it to the Chinese Grammar Wiki, which I worked on in its early stages. It’s an amazing project, and is a little different to our site. Rather than being half-blog, half-FAQ like ours, it’s a full and comprehensive encyclopaedia of Chinese grammar with a super-clear structure and design – take a look!

—

Ash Henson – Avid language learner, after working as an engineer for 8+ years, left to pursue a language-related career. Currently working on a PhD in Chinese at National Taiwan Normal University. Research interests include Old Chinese phonology, Chinese paleography, the Chinese Classics and excavated texts.

In modern language learning, far too much time is spent on learning to read and write, while speaking and listening are often given the back seat. Reading and writing are important (very important, actually), but should come only after the sound system of the target language has been acquired.

So what does this have to do with grammar? We all learn the grammar of our native language by listening to our parents and those around us talk. Everyone generally agrees that native speakers of a language outperform non-native speakers. Part of this may be due to biological factors (though this may not be as important as you might think, people can and do learn other languages to native or native-like levels all the time), but part of it has to do with the way languages are learned. Sound plays a huge role in properly acquiring a language. Because they can put a barrier between the learner and the actual sounds of the target language, reading and writing too early in the learning process can actually hinder proper acquisition. For example, thinking of tones as numbers if you haven’t yet mastered the actual tone contours puts an unneeded level of abstraction between you and the actual sounds of the tones. Always try to understand the actual sounds rather than the symbols used to represent them (which are useful only AFTER the actual sounds have been acquired).

When we hear non-native speakers make grammar mistakes in our native language, we know a mistake has been made because it “sounds wrong.” What that really means is, faulty sentences (i.e., a pattern or collection of sounds) go against the vast internal database we have of what our language sounds like. How we should learn grammar, then, is the answer to the question, “How do we develop the ability to know that something “sounds wrong” in the target language?”

Obviously, building up an internal database that could match a native speaker would take quite some time, but I think the old 80-20 rule can be applied here. For each grammar structure that you want to master, memorize five sentences that incorporate that structure by listening, repeating and mimicking a native speaker saying those sentences. For tonal languages such as Chinese, you might want to spend some time (perhaps a significant amount) practicing tones and tone combinations before you do entire sentences. When doing these things, you want to be thinking ONLY about the sounds and how to mimic them. You should avoid thinking about things like spelling, meaning, and grammar. Once you have the sentences memorized, go back and look at the grammar rule that they incorporate and you should be able to understand it on a more intuitive level.

We are most vulnerable to influence from our native language when we don’t know how to phrase something in the target language. Spending a lot of time mimicking native speakers in their pronunciation, rhythm, phrasing, word usage, etc. will minimize the influence our native language has the new language and help us to speak the target language in a much more natural way

—

David Moser holds a Master’s and a Ph.D. in Chinese Studies from the University of Michigan, with a major in Chinese Linguistics and Philosophy. David is currently Academic Director at CET Chinese Studies at Beijing Capital Normal University, an overseas study program for U.S. college students, where he teaches courses in Chinese history and politics.

Grammar is first learned intuitively, absorbing rules subconsciously, by example. Therefore, the absolute best way – really the only way – to learn Chinese grammar is to speak Chinese with Chinese people. Only when you’ve reached a certain level of mastery will grammar rules even make sense to you. So by all means read the grammar books; they are useful stepping stones. But the most reliable Chinese grammar is not in books, it’s in the heads of Chinese speakers. Seek out or create, by hook or crook, an environment where you are constantly interacting with Chinese speakers. If you’re not in China, don’t worry, there are Chinese people everywhere in the world. Find them, befriend them, and talk with them. You can also find them online, on Weibo, or Facebook, or on WeChat, it doesn’t matter. Set up a situation, no matter how artificial, in which you are communicating constantly in Chinese.

Here are some hints on how to make the best use of your Chinese friends to improve your grammar:

(1) Enlist your Chinese friends to actively correct your mistakes. This is not as easy as you might think. Most people are reluctant to correct your grammatical errors, thinking it to be impolite or distracting. In addition, it’s natural for people to care more about content than form — grammar won’t even be on their radar. You may have to keep reminding them – or even beg them – to point out your mistakes.

(2) Work on very specific linguistic goals. “Chinese grammar” is an impossibly broad domain; narrow your goals down to specific tasks. The grammar will come naturally, as different discourse types demand different structures; for example, teaching a Chinese friend how to play guitar (the ba把construction); recounting the plot of “Game of Thrones” (time and aspect); or simply explaining why in the world you’ve decided to learn Chinese (resultative suffixes, the grammar of hopefulness). Whatever it is, begin by collecting crucial patterns and sentences, and worry about the grammar later.

(3) Be attentive to “unconscious corrections” from your friends. When you make a grammatical error, you will often find that the person you are speaking with will, in their reply, take your imperfect utterance and automatically revise it to be in accord with their internal grammar. These “unconscious corrections” are linguistic gold – hoard them!

(4) “Cheat” by Googling. If you’re wondering if a certain grammatical structure you’re using is idiomatic, you can always Google it. If a native speaker produced a similar utterance in writing somewhere on the Internet, it’s pretty safe to assume it’s at least grammatically legal. For example, if you’re wondering how to say “Allow me to introduce myself” in Chinese, you can simply take a few guesses (“让我介绍我自己”, “请让我自我介绍一下”, “我把自己介绍给你”, etc.), and then search to see the range of grammatical possibilities.

—

Alan Park has been studying Chinese for 13 years and previously worked in China with Chinese clients as a management consultant. Currently, he is the founder of FluentU, a site that brings language learning to life with real-world video content.”

The conventional wisdom on Chinese grammar is that it’s easy. That the hard parts are tones, pinyin, characters – basically anything except grammar. But I think it’s totally wrong. Chinese is more different from English than romance languages, and that’s what makes it hard.

Some of the tricky issues are: unusual word order, new concepts that have no real counterpart in English (eg. 了), and grammar patterns which seem to be deceivingly similar (eg. the de particles 的, 得, and 地, which all sound the same). I would not recommend that Chinese learners gloss over these tricky grammar, and assume that they will figure it out through osmosis.

What learners really need is a targeted approach. First, they should try to understand the underlying concepts with a quality grammar book or Chinese learning website like Hacking Chinese. Then, they should try to collect examples of those grammar points. Then they should be as aggressive as possible in actually practicing them and getting feedback from a teacher. Learning grammar, like learning Chinese, isn’t something that can be done by just passively reading a book. It has to be done through the creation of muscle memory, which comes from falling on your face over and over again.

Of course, this isn’t to say that you shouldn’t supplement it with quality examples and explanations of the concepts. Beginners or intermediate learners might find this blog post helpful: 13 Mandarin Chinese Grammar Patterns and Structures We Love to Hate. We identified some of the most challenging grammar points (eg. the de particles, 会 vs 能, 想 vs. 觉得), and tried to provide concise explanations that would really make the light bulb go off in learners’ heads.

—

Roddy, who runs Chinese-forums.com, which celebrated its tenth birthday earlier this year. The site covers discussions on many topics related to China and Chinese – textbook choices, recommended authentic materials, studying at Chinese universities, and plenty more.

I think if at any point you’re sitting down to “study grammar” then you’re doing it wrong. If you’re following some kind of progressive course (which I’d recommend, even if you’re also getting tonnes of real exposure) that should introduce, explain and apply new structures at a reasonable pace. If you hit something that seems problematic, or you happen to hear something three times in a day and can’t resist looking it up, fair enough, open the grammar book. But otherwise make it a part of all your other learning, not something you do separately.

But each to their own. I’ve probably told this story before, but when I went back to the UK after my first year in China I signed up for an evening course in Chinese at the local university. One of the other students was an elderly professor of history who was, to be fair, awful at Chinese.

Chatting with him during the break one day I asked if he had any plans to go to China. No, he said, can’t imagine ever doing that. Chinese family or friends? Oh no, not that I can think of. Research interest in China? No, no. So why Chinese, in that case? Oh, he said, leaning in to divulge the big secret… I just love the grammar.

—

Albert Wolfe started learning Chinese on his own when he came to China in 2005. He is the author of Chinese 24/7: Everyday Strategies for Speaking and Understanding Mandarin and a novel faceless and the blog LaowaiChinese.net.

How to learn grammar is both scary and controversial. It’s scary because many adult learners have grammar phobia. (I think it’s one of the top three scholastic fears along with math and tests.) If you don’t feel that way, that’s a huge advantage. If you do, just relax: you’ve already learned at least some grammar!

One of the most important controversies is inductive vs. deductive approaches. But personally I think both are great! So I highly recommend trying to figure out grammar rules from a bunch of sentence examples (inductive) and also reading resources like John’s Pasden’s excellent Chinese Grammar Wiki (deductive) to fill in the gaps.

One more little tip: learning your native language as a kid and learning a foreign language as an adult are two very different processes. So don’t fall into the trap of over-comparing those two experiences.

—

Chinese Forums – This is the only answer not delivered by an individual, but is instead the collected wisdom of Chinese Forums. The thread can be seen here and contains many interesting ideas and useful insights. I have selected a few to include in this article, mostly dealing with areas not covered by the above answers.

Li3wei1 on the difference between learning grammar in Chinese and many other languages:

I’d say in most other languages, there’s a lot of memorising that you have to do up front even to produce basic sentences: verb declensions, genders, irregular verbs. That is not necessary in Chinese, but in Chinese, when you get to the advanced level, there are hundreds of structures and patterns that need to be memorised. So the memorisation load comes later in Chinese than in other languages, at least as far as grammar is concerned.

Adam about the learning sequence:

In my case, I learned “street Chinese” for the first few years. I used characters like 就 and 才 in my speech without knowing why they were there or what their purpose was, just because that’s how I had “heard” it. It was only later, when I enrolled in formal classes that the grammar rules were explained to me. It made a lot more sense to me to see then because I had already observed all the use cases.

And finally, a recommendation from lakers4sho:

For each grammar point that I learn or revise, I write my own 例子 using the structure, not trying to make it as complicated, but actually trying to make it as simple as I can, just so that I can apply the structure correctly. I show the sentences to my teacher (this is important, make sure you ask someone who knows their grammar) and she can tell whether they are correct or not.

—

That’s all from the expert panel for now. If you have any questions, comments, opinions or experiences related to learning Chinese grammar, just leave a comment! I’m sure you’re not the only one who wants to ask that question and if you share what works for you, it’s quite likely it might work for someone else too!

Tips and tricks for how to learn Chinese directly in your inbox

I've been learning and teaching Chinese for more than a decade. My goal is to help you find a way of learning that works for you. Sign up to my newsletter for a 7-day crash course in how to learn, as well as weekly ideas for how to improve your learning!

17 comments

Olle,

First, it caught my eye that you have some “sponsor” ads now on the site and one of them is Pleco. Congrats! I’d imagine they are paying you to list ads here, and that is a huge success. I’m really happy for you. Finding a way to monetize our mandarin Chinese is no small thing. Pleco is a big player and if Mike is willing to pay you to advertise on your site that is no small thing! It is an endorsement and validation of your site in itself.

Second, I like the concept of your “ask the experts” section very much. In fact, I look forward to reading their comments very much. However, I find this post and the previous “ask the experts” a bit overwhelming, namely too much content for ONE post. So, I’m wondering, is it possible that you can break all this content up into several successive posts, that you would post one after another a few days or a week, all in a row? e.g. Monday start the topic with some comments from one or two experts, Tuesday continue the topic with a few more experts and their comments, keep this going with one post a day until all the expert comments have been posted.

For me, that would make it easier to digest. ; )

Either way, nice work, and kudos to you and the success of the site!

The first expert panel article was way too long (perhaps even twice as long as this), so I thought it would automatically get better with shorter and fewer answers. Still, I think you’re right, though, I should probably split the article into several shorter ones. Even if people could read one third of the article now, one third on Thursday and the final third during the weekend, I don’t think many people do so now. So I agree, it makes sense to split the article and I will probably do that next time!

Totally.

Great plan.

Like studying Chinese, segmented, bite size chunks of learning is better than the “super sized” make you sick and dizzy McD’s meal. haha

Look forward to the next round…

As stated though, great concept with the “ask the experts”… keep it coming! ; )

My own experience (almost 19 years of learning/working with Chinese, including many years of teaching it) was that we learned grammar as part of the general learning process through our general language textbooks at both my British and year abroad (Taiwan) universities. Language points (grammar, if you like) were explained to us at the time, but it wasn’t studied as a subject on its own.

When we got back for the third year of our BA(Hons) studies, suddenly grammar workshops appeared in our timetable and grammar workbooks featured on the reading lists. At that point, we really knew most of the grammar there is to learn, but we were reviewing and developing our knowledge and command of its usage. It was actually extremely helpful at this stage, but I think would have been off-putting any earlier on.

Some of the new self-study texts for those in the early stages such as ‘Chinese Demystified’ and ‘Practice Makes Perfect: Basic Chinese’ teach grammar alongside practical language usage in a well blended manner just like we learned in uni classes, so I think this sort of book is good for self-study and classroom supplementation for those who need it.

As for me now, I find regular review of grammar workbooks etc to be immensely helpful in keeping my Chinese relatively error free as we all know how easy it is to forget the simple stuff in our accumulation of more complex material.

Add oil, all!=)

Ash Henson’s contribution is 100% correct. Grammar is almost wholly intuitive and cannot really be integrated into one’s automatic thought processes merely from reading grammar books. His analysis of how the first language interferes with using the second language is also correct. We have to build up a “database” of sounds and expressions in the second language so that we do not draw on the first language. The way to do that, again, is to use direct experience with native speakers, not grammar textbooks. Finally, his last question about how do we know something sounds wrong shows that grammar has more to do with memory and that internal database than memorizing sentences and rules from textbooks.

Well, even in English as a first language, it is said that ‘We all learn grammar so that we can eventually forget it.’

I think it is only appropriate to discuss the actual utility of grammar by first presenting a real history of its origin.

A. It was a method for non-Latin speakers to study what was essentially a deal language by disassembly. This may be a strong indication of why it often interfers with productive spoken dialogue.

B. Even your introductory definition above presumes it applies to written text — not colloquial spoken language.

C. Rule based language production is never going to be as natural as native language that fully embraces all the nuance of emphasis. Emphasis is so often done by presenting thinks in an odd way – either breaking a rule, bending a rule, or just throwing out an idiom.

Don’t hang your whole future with Chinese on grammar. It will never work out well. Listen and observe what real people say, in what context, and the real impact of it.

A few more thoughts came to mind…

My experience with grammar is a very deep involvement with teaching English grammar to 2nd language students in Taiwan. I have studied Chinese grammar and have a collection of several well-known texts.

From all this experience with grammar in both English and Chinese over 20 years, I see that it is mainly a working hypothesis, not set in stone.

For example, I was taught in school in the USA about the 8 parts of speech making up grammar, but I find no consensus of what all 8 parts are. At the other extreme, I have deeply studies Quirk and Greenbaum’s exhaustive English grammar that is 1200 pages long and have a list of several omissions and errors that I specifically avoid when teaching English.

On the Chinese side, none of the Chinese Grammar texts I have really agree with the others. So it seems to imply that in Chinese as well, grammar is a working hypothesis — not iron-clad rules for production of proper Chinese..

In a communicative setting, the rules get in the way. And since Chinese grammars seem to identify movable and not movable adverbs, there is obviously NOT on sentence pattern that fits all situations. Also, one of the worst practices of Chinese grammars is to identify the ‘bound form’. It is not a proper unit for grammar as it is merely a portion of a word, such as a prefix or a suffix. These half-words merely confound new learners that are trying to analyize the phrases and meaning.

Grammar provides overview and review of identified patterns, but it will never provide all of spoken language. A lot of spoken language is utterances and idiom, and many times the communication succeeds with a partial phrase because both parties understand the context.

Any idea of when John Pasden’s upcoming seperate article will be posted? Or David Moser’s from the last panel?

Good question! It’s really up to them. I have sent e-mails to both of them to see if that will encourage them to finish the articles. 🙂

I’ve been studying Mandarin off-and-on since marrying my Taiwanese wife 16 years ago. My wife loves to say, “Mandarin has no grammar rules.” However, when I try constructing a new sentence using words I know, she’ll often correct me and rearrange the word ordering. My quick response is always, “I thought Mandarin had no grammar rules.”

Another random comment about grammar (more specifically, sentence patterns)… Although I’ve collected around 100 patterns, looking at the text of a modern-day drama show on Taiwanese television, there are many, many sentences that don’t come close to fitting into any of these patterns.

BTW.. Love the Hacking Chinese site. I haven’t had time yet to take a deep dive but it’s great knowing it has a lot of great info.

None of the panel members explicitly addressed how to approach grammar when teaching Chinese to children. However, the approach outlined by John Fotheringham I believe would be the most effective – not only for children, but for adults too!

Grammer is the basic step in learning any language. And when it comes to learning Chinese, it is very essential to learn basic grammer. In simple terms grammer is the building block in learning any language.

I think Grammer is very important, you can learn any language, but Grammer is the foundation for that, thanks