Digital dictionaries make reading Chinese easier, but they might also prevent you from learning essential strategies. Let’s have a look at why using a good dictionary can be bad for your reading ability!

Digital dictionaries make reading Chinese easier, but they might also prevent you from learning essential strategies. Let’s have a look at why using a good dictionary can be bad for your reading ability!

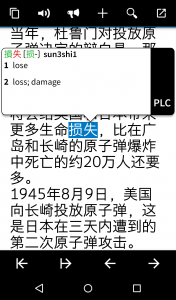

Reading digitally helps you avoid spending most of your time flipping through pages in a printed dictionary, looking for the right entry, allowing you to focus on the text itself. This has indeed revolutionised Chinese reading.

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode (#246):

Available on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube and many other platforms!

Why using a good dictionary can be bad for your Chinese reading ability

Could it be that your Chinese reading ability might suffer because of easy access to dictionary look-ups through great apps like Pleco or Hanping?

Yes, unfortunately.

The situation is analogous to other cases where we get too much support. For example, when learning to ride a bike, it would seem like using training wheels is a good idea because they stop you from falling over, but this is not the best method.

Why?

If you want to learn to bike quickly, don’t use training wheels

Because it helps you too much and prevents you from building the skills you need to ride a real bike. If you’re curious, balance bikes are usually a better option because they allow you to develop skills that transfer better to a normal bicycle (see Mercê et al., 2022 and 2025). Something similar can happen if you sprain your foot; many people tend to use crutches longer than they should, and this extra support can slow your recovery.

In this article, I will discuss the downsides of having easy access to definitions of words when reading in Chinese. I’m particularly interested in what you might be missing out on in terms of useful strategies and skills.

There are other examples of support that actually turn out to be bad for you when learning to read Chinese, such as relying on Pinyin for too long, but that won’t be covered in this article.

If you’re curious about the role of pinyin, have a look at this excellent post over at Mandarin Companion: Pinyin over characters: the crippling crutch.

A paperless revolution in Chinese reading

Before we look at the downside of relying too much on digital dictionaries when learning to read Chinese, let’s not forget that these are often extremely useful, indeed essential, when used correctly.

In the article linked to in the introduction above, David Moser argues that digital dictionaries have revolutionised the process of learning to read Chinese.

I wholeheartedly agree; digital reading has an overwhelmingly positive impact on learning Chinese. In this article, I assume that you already understand the potential benefits, so if you haven’t checked out his article, I suggest you do so before continuing to read this one. Here’s the link again:

The new paperless revolution in Chinese reading

Digital dictionaries: an essential aid or a crippling crutch

In some cases, the answer to whether something is an essential aid or crippling crutch depends on what your goals are.

In some cases, the answer to whether something is an essential aid or crippling crutch depends on what your goals are.

For example, while it can be argued that wasting time flipping pages in a dictionary is just a waste of time, it’s not so obvious that typing is always better than writing by hand, even if it’s faster.

Typing is a very useful tool for producing text quickly, but if you value the ability to write Chinese characters by hand, you should know that always typing will have a negative impact.

When it comes to reading and easy access to the meaning of vocabulary (via word lists, pop-up dictionaries or similar), I believe that this is mostly a good thing. It allows you to read text at a more advanced level without spending 90% of your time with your nose in a dictionary.

Being able to look something up by just tapping the word can make reading in Chinese much more enjoyable and lead to better results in general. However, always reading Chinese digitally with easy access to dictionary look-ups does come with a cost.

Useful strategies that easy access to dictionary look-ups stop you from learning

The problem is straightforward: by relying too much on a tool, you end up not being able to function properly without it.

What was meant to support your learning helps you take shortcuts that prevent you from learning the necessary skills and strategies yourself.

Drawing on the research of Hosenfeld (1986) and Harris (1997), we can list a number of reading strategies that successful students use when reading in a foreign language. For a more recent meta-analysis of meta-cognitive reading strategies in a second language, check Yapp, Graaff and van den Bergh (2021).

Developing these skills and strategies takes practice, which you don’t get if the answer is always just a tap away.

- Relying on prior knowledge of the world – One of the major benefits of learning a language as an adult is that you already know a lot about the world, which can be very helpful when learning to read Chinese. I’ve written about this in more detail here when it comes to listening ability, but the same principles apply to reading ability too.

- Use of contextual clues such as headings, pictures and type of text – You can learn much about a text by just looking at the way it’s formatted, what the pictures show and how the text is structured. But if you always use your dictionary, you don’t really need these clues.

- Aiming for the gist rather than detailed comprehension – Sometimes you have no idea what a word means, but that might not stop you from understanding the sentence it’s in. Reading without resolving all ambiguities is a skill you need to learn.

- Use of syntactic (grammatical) knowledge of the language – Even if you have just studied Chinese for a short period of time, you do know something about word order. Experienced readers can figure out what types of words make sense in a certain position and thereby make it much easier to guess their meaning and function in the text.

- Analysing the structure and components of unknown words – Most Chinese words are composed of two characters. Even if you don’t know the word, perhaps you know the characters. But if you just tap to reveal the answer, you never learn to do this.

- Persisting instead of giving up – When you know you have the answer just a click away, it’s tempting to just reach for it the second you need it. Reading a text without a dictionary will then be terribly frustrating.

- Forming hypotheses about the meaning of unknown words – Based on all of the above, successful readers form a hypothesis of what the unknown word means. This takes longer than just tapping the word.

- Evaluating these hypotheses based on subsequent text – Naturally, you don’t know if your hypothesis is correct, you just know that it fits the observed facts so far. If you always look everything up, you never need to evaluate your hypotheses.

Being a good reader is about much more than knowing words and grammar. Mastering these reading strategies is essential, but relying on a dictionary too much will stop you from doing that.

Beyond tīng bu dǒng, part 3: Using what you already know to aid listening comprehension in Chinese

Conclusion: mix it up; vary your reading

My suggestion is not to go back to reading only printed books with the aid of printed dictionaries. No, I still think you should do most of your reading digitally with all the support and scaffolding you can get; reading in Chinese is hard enough as it is. This will enable you to read much more, and you will also enjoy the process, which is in itself valuable.

However, I don’t think you should do that all the time. Put away your digital device occasionally and read something printed on paper, or at least commit to not using any digital tools to aid your reading. You can also try using the rule of three, i.e. only look something up when you see it the third time and still don’t understand it. This allows you to understand important things in the text you’re reading, while avoiding the problem of looking everything up.

And even when reading with a dictionary, employ the strategies I’ve listed above and see if you can’t understand Chinese text even without a dictionary. It will require you to adopt a much more active attitude towards the text you’re reading, but research clearly shows that this is the way to go for long-term reading ability and literacy.

References and further reading

Everson, M. E., & Xiao, Y. (Eds.). (2009). Teaching Chinese as a foreign language: Theories and applications. Boston: Cheng & Tsui. Chapter 5: Literacy Development in Chinese as a Foreign Language.

Harris, V. (1997). Teaching Learners How to Learn: strategy training in the ML classroom. London: Cilt.

Hosenfeld, C. (1984). Case studies of ninth grade readers. Reading in a foreign language, 4, 231-249.

Mercê, C., Branco, M., Catela, D., Lopes, F., & Cordovil, R. (2022). Learning to cycle: from training wheels to balance bike. International journal of environmental research and public health, 19(3), 1814.

Mercê, C., Catela, D., Cordovil, R., Bernardino, M., & Branco, M. (2025). Learning to Cycle: Body Composition and Balance Challenges in Balance Bikes Versus Training Wheels. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 10(1), 53.

Smith, S., & Conti, G. (2016). The Language Teacher Toolkit. Createspace Independent Publishing Platform. Chapter 8: Teaching Reading.

Yapp, D. J., de Graaff, R., & van den Bergh, H. (2021). Improving second language reading comprehension through reading strategies: A meta-analysis of L2 reading strategy interventions. Journal of Second Language Studies, 4(1), 154-192.

4 comments

Really interesting article. One strategy I use related to this is only looking up an unknown word the 3rd time I come across it within the same text. This rule gives me time to deploy some of the guessing and inferencing techniques Olle mentions before going for Pleco, and helps me learn the word more quickly.

Yes, I usually recommend that too, not only for this reason, but because it’s usually not necessary to learn a word unless it occurs a few times in a text. Learning everything is always a bad idea, unless the text is tailored for the specific student in question.

This article feels bizarre considering it in light of the recent uprooting in the US and more widely publicised criticism of Whole Language Approach. Which basically applied those reading strategies except to first language.

The reading stategies aren’t a good reader method, they are a poor reader method and are also a crutch. Of course in second language we will generally initially be poor readers because in most cases we don’t learn to read a language which we already largely know in spoken form but do everything concurrently. So in the end we need to rely on some crutches. So the discussion is from the initial point should be which crutches are more advantageous, but this values one over other without supporting this with any arguments.

Is being able to actively guess the meaning in situations where you can’t actively check it better or is quickly learning the meaning that will likely be the correct one instead of risking remembering incorrect guess better?

I would bet that this largely depends on the situation you are in.

But it’s kind of nonsensical to reach for old research here, since they can’t compare the situations. You should also address it directly and not just throw a list at the end.

Thank you for your comment! I agree there are many ways to approach this, and conclusions depend on the specific situation. My goal with this post isn’t to discourage dictionary use in general. Instead, I’m highlighting certain important reading skills, like guessing from context, that need practice. Immediate translation doesn’t usually help build these skills.

I used older research mainly for convenience and clarity, but there’s plenty of newer research supporting inference and context-based guessing in second language learning. Unlike the whole language vs phonics debate, which deals mostly with first-language reading instruction, my focus is on adult learners of Chinese on all levels. From what I’ve read, in second-language contexts, meta-cognitive reading strategies are generally regarded as being critical for L2 reading. Here is a fairly recent meta-analysis on L2 reading strategies: Yapp, D. J., de Graaff, R., & van den Bergh, H. (2021). Improving second language reading comprehension through reading strategies: A meta-analysis of L2 reading strategy interventions. Journal of Second Language Studies, 4(1), 154-192.

Over-reliance on dictionaries is also a real and common issue I’ve observed teaching Chinese. Students often feel anxious or stuck when faced with unknown characters without immediate translation. My suggestion isn’t to stop using dictionaries entirely, but rather to occasionally practise reading without one or limit its use.

Finally, it’s certainly possibly to avoid crutches, or at least limit their use a lot, by focusing on extensive reading of easier texts.