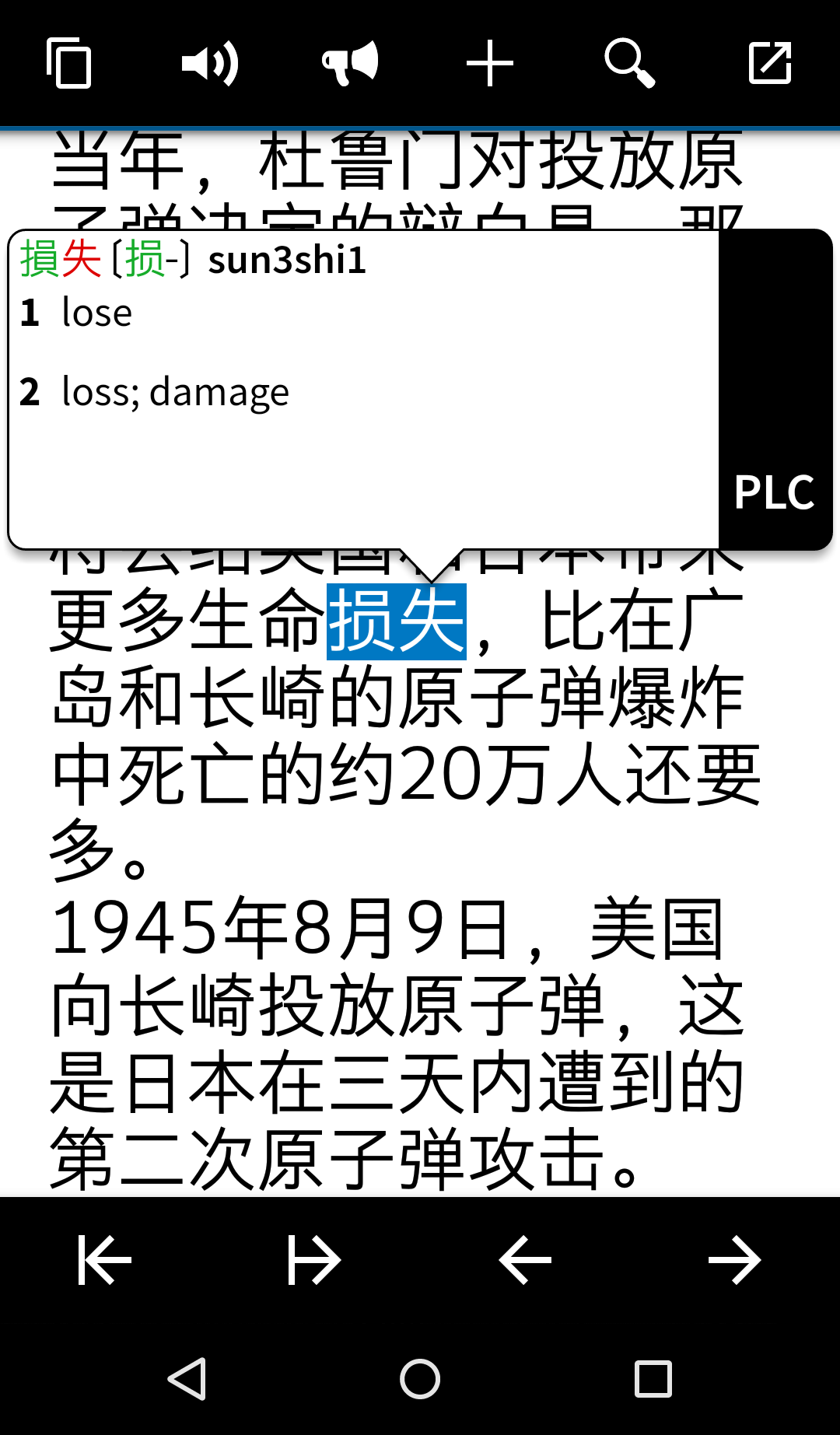

Using the right tools can make learning Chinese considerably easier. Compare using a paper dictionary with a modern app like Pleco: In the former case, you will spend most of your time flipping through pages, looking for the right entry; in the latter, you are served the answer almost immediately. This has indeed revolutionised Chinese reading.

Using the right tools can make learning Chinese considerably easier. Compare using a paper dictionary with a modern app like Pleco: In the former case, you will spend most of your time flipping through pages, looking for the right entry; in the latter, you are served the answer almost immediately. This has indeed revolutionised Chinese reading.

However, as I argued in my article about how technology can stop you from learning Chinese, relying too much on digital tools can have a downside.

Why using a good dictionary can be bad for your Chinese reading ability

Could it be that your Chinese reading ability might suffer because of easy access to dictionary look-ups through great apps like Pleco? The answer is yes. The situation is analogous to other cases where we rely too much on support of some kind. For example, if you have sprained your foot, using crutches can actually slow your recovery, and if the training wheels are never taken off the bike, learning to ride it takes longer.

In this article, I will discuss the downsides of having easy access to definitions of words when reading in Chinese. I’m particularly interested in what you might be missing out on it terms of useful strategies and skills. There are other examples of support that actually turns out to be bad for you when learning to read Chinese, such as relying on Pinyin for too long, but that won’t be covered in this article. If you’re curious about the role of Pinyin, have a look at this excellent post over at Mandarin Companion:

Pinyin over Characters: The Crippling Crutch

Easy dictionary look-ups: Crippling crutch or essential aid?

Before we look at the downside of relying too much on digital dictionaries when learning to read Chinese, let’s not forget that these are often extremely useful, indeed essential, when used correctly.

In the article linked to in the introduction, David Moser argues that digital dictionaries have revolutionised the process of learning to read Chinese.

I wholeheartedly agree; digital reading is to a very large extent something good. In this article, I assume that you already understand the potential benefits, so if you haven’t checked out his article, I suggest you do so before continuing reading this one. Here’s the link again:

The new paperless revolution in Chinese reading

In some cases, the answer to whether something is a crippling crutch or an essential aid also depends on what your goals are.

For example, while it can be argued that wasting time flipping pages in a dictionary is just bad, it’s not so obvious that typing is always better than writing by hand. Typing is a very useful tool for producing text quickly, but if you value the ability to write Chinese characters by hand, you should know that always typing will have a negative impact.

When it comes to reading and easy access to the meaning of vocabulary (via word lists, pop-up dictionaries or similar), I believe that this is mostly a good thing; being able to look something up by just tapping the word can make reading in Chinese much more enjoyable and lead to better results in general. However, always reading Chinese digitally with easy access to dictionary look-ups does come with a cost.

Useful strategies that easy access to dictionary look-ups stop you from learning

The problem is straightforward: By relying too much on a tool, you end up not being able to function properly without it. What was meant to support your learning helps you take shortcuts that prevent you from learning the necessary skills and strategies yourself. Let’s look at what you could miss.

Drawing on the research of Hosenfeld (1986) and Harris (1997), we can list a number of reading strategies that successful students use when reading in a foreign language. I have selected those that are most relevant for this article and provided my own examples:

- Relying on prior knowledge of the world – One of the major benefits of learning a language as an adult is that you already know a lot about the world, which can be very helpful when learning to read Chinese. You’re well equipped to understand a story in a train station, because you know quite a bit about train stations, why people go there, what they do there, what functions you expect to find there and so on. Not everything you’ve learnt about train stations in your home country is applicable to a text about a Chinese train station, but most things are.

- Use of contextual clues such headings, pictures and type of text – You can learn much about a text by just looking at the way it’s formatted, what the pictures show and how the text is structured. This information helps you with reading comprehension if you pay attention to it. Many standardised exams in Chinese mimic authentic genres of text and might present a reading question which is formatted as a time table or an ad in a newspaper.

- Aiming for the gist rather than detailed comprehension – Sometimes you have no idea what a word means, but that might not stop you from understanding the sentence it’s in. Or if it does, you might still be able to understand the main point in the paragraph. This is essential for reading speed, since stopping and thinking about each unknown word is not an option for standardised exams, where speed is a concern from most students.

- Use of syntactic (grammatical) knowledge of the language – Even if you have just studied Chinese for a short period of time, you do know something about word order. This can greatly help you guess the meaning of an unknown word. If you see a measure word in front of the unknown word, it’s probably a noun; if you see 过 / 過 right after it, it’s probably a verb. Taking this into consideration will increase your ability to guess the meaning.

- Analysing the structure and components of unknown words – Most Chinese words are composed of two characters. Even if you don’t know the word, perhaps you know the characters. Or you know one character. Or the semantic component of one or both (the semantic component is usually on the left). Simple examples of this are words that include semantic components like 木 (usually trees), 金 (usually metals) or 魚 (fish or at least water-dwelling creatures).

- Persisting instead of giving up – When you know you have the answer just a click away, it’s tempting to just reach for it the second you need it. However, simply reading the sentence again and thinking about it for a moment or two might do the trick.

- Forming of hypotheses about the meaning of unknown words – Based on all of the above, successful readers form an hypothesis of what the unknown word means. This needn’t be explicit or even conscious, but it can be. One strategy is to translate to one’s native language, which might give easier access to a range of possible meanings.

- Evaluating these hypotheses based on subsequent text – Naturally, you don’t know if your hypothesis is correct, you just know that it fits the observed facts so far. As you keep reading, you can usually evaluate the truthfulness of your hypothesis and adjust. If you think the word was probably a drink of some kind, you know you’re wrong if the person then proceeds to eat it in the next sentence.

Most language teachers are aware of these skills and will help their students to acquire them, and it’s also a part of many curricula for teaching foreign languages. However, you will only learn these strategies if you actively use them when reading. You will not improve your ability to deal with an unknown word if your first action is always to look it up and move on a second later when you’ve seen the English translation.

Naturally, as was the case with typing and handwriting, quick dictionary look-ups can be both a crippling crutch and an essential aid. If you assume that you won’t need to write by hand, always typing is great. Similarly, if you assume that you will always have a pop-up dictionary available, you’ll be fine without the strategies I listed above.

However, when it comes to reading, you can’t be as sure as you can be with handwriting. For instance, I almost never write by hand in Chinese outside the classroom, but I do read stuff on paper all the time, even in Sweden (books, restaurant menus, notes, on a computer that isn’t mine, and so on). Sure, you can use fancy Optical Character Reading (OCR) features on your phone and look words up that way, but that really isn’t very practical (yet). What about if you sit a formal exam?

It could be argued that if you’re incapable of reading a text without easy access to a dictionary, you don’t actually know how to read the text. Perhaps this will change in a future of cybernetics and augmented reality, but for now, your phone is not an integrated part of you.

Conclusion: Mix it up; vary your reading

My suggestion is not to go back to reading only printed books with the aid of printed dictionaries. No, I still think you should do most of your reading digitally with all the support and scaffolding you can get; reading in Chinese is hard enough as it is. This will enable you to read much more and you will also enjoy the process, which is in itself valuable.

However, I don’t think you should do that all the time. Once in a while, put away your phone and read something printed on paper. Don’t reach for Pleco the moment you run into trouble, see if you can employ the strategies I’ve listed above to get at the meaning of the word anyway. If you still don’t understand enough to get the gist, read something easier.

References and further reading

Everson, M. E., & Xiao, Y. (Eds.). (2009). Teaching Chinese as a foreign language: Theories and applications. Boston: Cheng & Tsui. Chapter 5: Literacy Development in Chinese as a Foreign Language.

Harris, V. (1997). Teaching Learners How to Learn: strategy training in the ML classroom. London: Cilt.

Hosenfeld, C. (1984). Case studies of ninth grade readers. Reading in a foreign language, 4, 231-249.

Smith, S., & Conti, G. (2016). The Language Teacher Toolkit. Createspace Independent Publishing Platform. Chapter 8: Teaching Reading.

Tips and tricks for how to learn Chinese directly in your inbox

I've been learning and teaching Chinese for more than a decade. My goal is to help you find a way of learning that works for you. Sign up to my newsletter for a 7-day crash course in how to learn, as well as weekly ideas for how to improve your learning!

2 comments

Really interesting article. One strategy I use related to this is only looking up an unknown word the 3rd time I come across it within the same text. This rule gives me time to deploy some of the guessing and inferencing techniques Olle mentions before going for Pleco, and helps me learn the word more quickly.

Yes, I usually recommend that too, not only for this reason, but because it’s usually not necessary to learn a word unless it occurs a few times in a text. Learning everything is always a bad idea, unless the text is tailored for the specific student in question.