When learning Chinese, some obstacles are easier to overcome if you have the guidance of someone who knows more than you do, such as a teacher or someone who has already learnt the language as an adult.

When learning Chinese, some obstacles are easier to overcome if you have the guidance of someone who knows more than you do, such as a teacher or someone who has already learnt the language as an adult.

This is indeed the reason this website exits; I share my experience and knowledge in the hope that it will make it easier for you to learn Chinese.

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to this article:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcast, Overcast, Spotify and many more!

It’s similar to enlisting the help of a personal trainer at a gym: if you’re new to working out, you can benefit greatly from some advice about how to work out and how to avoid some common problems.

However, there are other obstacles where the benefit of guidance is more questionable, which is what I want to talk about in this article. More specifically, I want to talk about whether or not it’s useful to receive guidance when it comes to basic listening and reading in Chinese.

Too much English in beginner learning materials

The typical example is a beginner podcast. Each episode is perhaps five minutes long and teaches a few short phrases and a bunch of words, all put into a slightly artificial dialogue. The dialogue lasts about 10 seconds. The dialogue is probably repeated once or twice, along with some repetition of the vocabulary, so if you’re lucky, you can get up to a whole minute of Chinese. This is not only true for podcasts, but also YouTube videos and similar. I will discuss the issue of too much English (or other source languages) again in an upcoming blog post.

Leaving the debate about how useful explicit instruction is aside (check this article for my general approach to this topic), I think we can all agree that it’s not good to spend 90% of your study time listening to someone talking in a language other than the one you’re studying. It’s great if you want to learn about Chinese, but your actual goal is to learn to listen, speak, read and write Chinese, which is something different.

Part of the problem here is the difference between feeling like you’re learning and actually learning something. Most people would likely consider listening to a beginner podcast as learning, but is that reasonable if a vast majority of the time is actually not in Chinese? If you logged study time, can you really write down “10 minutes listening” if there was only one minute of Chinese in there? Never forget that how much you learn is about seconds, minutes and hours spent studying, not how many months or years have passed since you started learning.

This illusion of learning is similar to the mistaken idea that highlighting text or rereading a book is a good way of learning the content; it sure feel silke studying, but you’re actually not learning that much. It’s also akin to the difference between taking a real university course and following a series of lectures passively with video or audio. The former requires you to engage with the content, the second does not. Guess which is more effective?

Getting exposed to the language and engaging with it

So, what’s the alternative, then, you might ask? Having even beginner podcasts entirely in Chinese? If you don’t understand the explanations if they are in Chinese, how else can they be conveyed except in English?

Well, the simple answer is that perhaps you don’t need most of those explanations in the first place, which removes the need of a language to convey them in.

Naturally, you need some support, because attacking something like written Chinese without any guidance is bound to be extremely difficult and frustrating. Can it be done? Sure, with the right learning materials. Do I recommend it for most students? Certainly not.

There are ways to provide limited amounts of support so that understanding becomes possible without actively explaining too much, though, which is what we will turn to next.

Learning vocabulary

When it comes to vocabulary, I prefer to learn the basic meaning of words through translation. This way, large amounts of vocabulary can be learnt very quickly through spaced repetition and other tools. While it’s cool to use pictures or very basic Chinese instead of translations, this is usually impractical and time-consuming (it’s hard to find good pictures) and much harder to review quickly.

The goal of such vocabulary learning is not to teach you everything you need to know to use the word, the goal is to provide you with key vocabulary so you can listen and read more, which will in turn lead to more active forms of knowledge. For example, building up quick and reliable audio recall for basic vocabulary can be very helpful and is free and easy to set up.

Learning grammar

When it comes to grammar, I prefer using lots of examples, starting out with two types of translations:

- Natural translation, which presents an idiomatically correct English sentence that captures the meaning of the original sentence. This helps you understand what the sentence really means and probably also how it’s used.

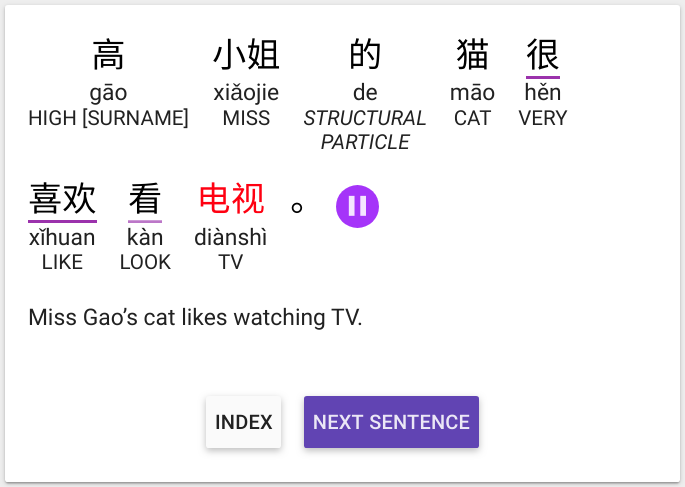

- Direct translation, which is done on the word level and produces sentences that no native speaker of English would utter, but which maintain the structure of the original Chinese. This is extremely helpful for figuring out how the sentence works, without using more than a few words of English (the meaning is shown rather than explained). The image below shows an example of how direct translation is used in my beginner course Unlocking Chinese.

If these two approaches fail or are unavailable, explicit explanations might be necessary to really understand what’s going on, I just don’t think that should be the first choice. If you’re looking for succinct and clear explanations of most grammar points you will encounter as a beginner or intermediate learner, I suggest you check out Chinese Grammar Wiki.

No pain, no gain?

If you rely on too much support and let someone guide you through every step of spoken and written Chinese, learning not only becomes incredibly boring and inefficient, I also believe it becomes less effective. There is merit in listening to or reading something many times, gradually piecing together what a passage means, instead of immediately having the answer presented for you.

This doesn’t mean that deep-end immersion is the solution for most people, it just means that you probably don’t need someone to talk you through every word, grammar pattern and sentence in your dialogue, text or whatever it is you’re studying. Look at the picture above with Miss Gao’s cat. Even if you were a complete beginner, doesn’t the direct translation provide you with enough information to figure out some basic things about word order and how the words in the sentence are used? If you studied a few hundred such sentences, wouldn’t that be enough to learn most of what you need?

Sure, checking a brief explanation of how some complex words like 的 or 了 work might be good at some point, but there’s no need to dive into a lecture immediately. In fact, you can learn most of what you need here simply by studying the structure of the sentence while paying attention to the natural translation at the bottom so you know what the whole sentence is supposed to mean.

I definitely think that learning should be fun, but I also know that truly engaging with content at your own level is very demanding. It’s great to switch gears to easier listening and reading material if you don’t feel up for dealing with more demanding content, but not if you do that all the time or substitute watching short videos about the Chinese language for actually engaging with the language.

Yes, too much guidance can make you learn less Chinese

There are a few things here to note. As a learner, examine the activities you engage in when you learn Chinese and see if they are actually as effective as you think they are. Are you perhaps confusing activities that are about Chinese with actually engaging with the language? For example, reading this article hopefully makes you more aware of this problem, but reading the article does not count as engaging with the language!

What steps can you take to increase the percentage of Chinese in the materials you’re using? A few ideas would be to simply ignore vocabulary and grammar explanations unless you really need them, cut out the dialogue in a podcast and focus only on that or focus on a podcast that uses more Chinese.

Help and guidance is usually well-meant, but that doesn’t mean it’s always good for you!

Tips and tricks for how to learn Chinese directly in your inbox

I've been learning and teaching Chinese for more than a decade. My goal is to help you find a way of learning that works for you. Sign up to my newsletter for a 7-day crash course in how to learn, as well as weekly ideas for how to improve your learning!

1 comments

Thanks so much again for the insightful article and even more one the effort of making the audio version!

多谢!