When learning Chinese characters, there are a number of things that can be really confusing if you don’t know what’s going on. One example of this is character variants and regional standards, which is what I will explain in this article.

This won’t teach you all the necessary cases, but it will help you understand how it works so you can then learn what you need. Here’s an example of what I mean:

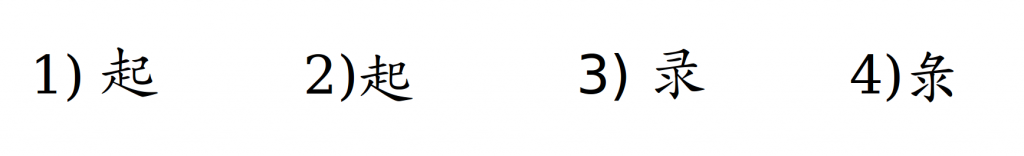

As you can see, 1 and 2 are slightly different, as are 3 and 4, but they are still the same characters. The first in each pair is the standard used in Mainland China, the second is used in Taiwan. However, this is not about simplified and traditional characters; these are not listed when enumerating characters that were simplified, for example.

Same but different

Instead, these are variants of the same characters. In handwritten Chinese, which variant you use matters little, and no one will misunderstand you if you write the “wrong” version. However, when using phones and computers, you will come across characters that are different from what you have learnt.

Each time I teach a beginner course in Chinese, I get questions about different fonts and computer characters that don’t look like the characters in the textbook or those that I write on the board. That’s what this article is about.

Familiar examples

Before we start, let’s look at two examples from English to give you an idea what this is about:

- g vs. ɡ

- a vs. ɑ

The former is common in print and digital texts, but the latter is much more common in handwritten texts. They are clearly the same letters, though.

Most people might not even notice which one you use! So, from a practical perspective, they are the same and both are recognised as the same letter, even though they look different.

Allography and character variants

This is called allography, and causes some problems when you learn Chinese characters. The same character can look slightly different depending on what region you’re in or what fonts you have installed.

Since this website is about learning Chinese, I will not talk about Japanese and Korean, but you should still be aware that characters can be written somewhat differently in these countries. Here’s an article about differences between Chinese and Japanese.

In Chinese, these character variants can be divided into two groups:

- Regional font differences

- Regionally preferred variants

Regional font differences

The first group contains characters that are identical from a code perspective (they have the same code point). In other words, if you have a digital text in Chinese including such characters, there is nothing that tells them apart. This means that if you use the wrong font, these characters will be written incorrectly! I have addressed this issue in a follow-up article.

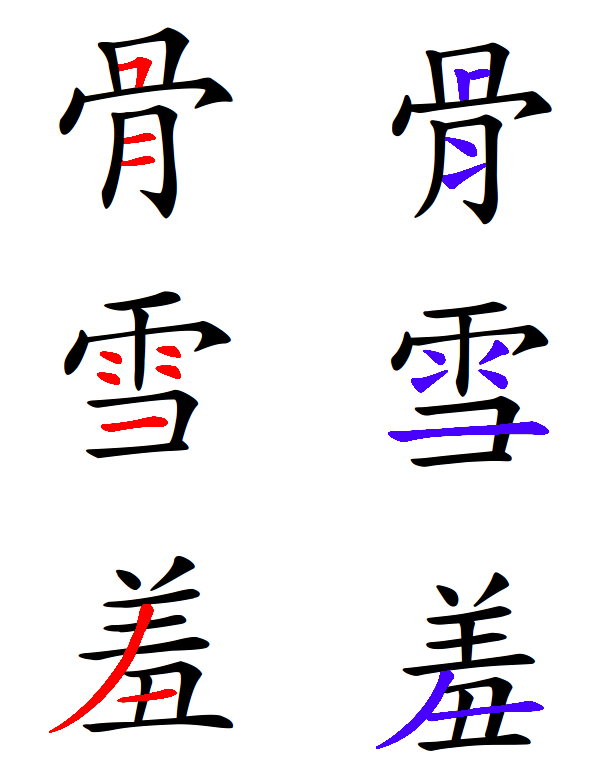

Here are a few examples (left/red is Mainland China, right/blue is Taiwan):

The fonts used in this picture are 方正楷体简体 and 教育部標準楷書.

The fonts used in this picture are 方正楷体简体 and 教育部標準楷書.

As you can see, using the right font is important! If you want to learn to write both simplified and traditional Chinese, it’s also a good idea to learn about these differences, even though they aren’t examples of character simplification.

Still, in practical terms, the dividing line is the same (the variants on the left are used in the same area as simplified characters and those on the right are used alongside traditional characters).

Regionally preferred variants

The second group consists of characters that have several variants, but where a different variant is preferred over the others in different places. Here’s an example:

- 户 (preferred in Mainland China)

- 戶 (preferred in Taiwan)

- 戸 (preferred in Japan)

This means that from a code perspective, they are different (they have different code points), so which one is displayed is not a primarily a font issue (although some fonts might merge them). In some dictionaries, these are actually listed as simplified/traditional in case they are different.

Here is a short list of characters for which the preferred variant is different (again, Mainland on the left, Taiwan on the right):

- 户 and 戶

- 录 and 彔

- 没 and 沒

- 换 and 換

- 黄 and 黃

- 奥 and 奧

- 别 and 別

- 刹 and 剎

- 冲 and 沖

- 羡 and 羨

- 抛 and 拋

- 吴 and 吳

To summarise, these can be written differently if the font is designed to do so (mine shows all of the above to be different). The other type we looked at cannot be displayed differently in the same font, as they share the same code point.

Other variant characters

It should also be noted that there is a very large number of variant characters and that some are so different that they they can’t be recognised as the same character unless you have studied both variants.

However, these are not used often and you shouldn’t encounter them too often. If you need to look them up, you can use this dictionary of Chinese character variants (use 單字查詢 to look up individual characters).

Conclusion

This article was meant to help you understand why some characters may be rendered differently depending on what fonts you use or where a character was printed. In the next article, I will look more at how to solve font problems. If you want to know more about how Chinese characters and fonts work, here is a short reading list:

- What’s the Difference between Simplified & Traditional Chinese, and are they Separate in Unicode?

- Unicode Chinese and Japanese FAQ

- Variant Chinese characers

- Han Unification

Tips and tricks for how to learn Chinese directly in your inbox

I've been learning and teaching Chinese for more than a decade. My goal is to help you find a way of learning that works for you. Sign up to my newsletter for a 7-day crash course in how to learn, as well as weekly ideas for how to improve your learning!

5 comments

You sure the red one on the left is mainland? My wife from Taiwan seems to disagree.

Which characters in particular do you refer to? The ones on the right use the standard Kaishu fonts issued by the Ministry of Education (Taiwan). This may or may not reflect the way your wife (or any other individual) actually writes.

What exactly do you mean by code point?

Does the preference for certain variants occur between regions inside Mainland China? Or maybe web vs printed versions?

The most frustrating part is that sometimes the difference between variants is bigger than the difference between different words 😅

example

裏 & 裡 – variants of the same traditional character

力 & 为 – totally different words, both simplified characters

And how these different variants survived coexisting as traditional forms?

A code point is an integer value that refers to a specific character in Unicode. If two variants share the same code point, they are effectively the same from the computers point of view. If the code point is different, it means that the characters can be represented differently (but it depends on the font). More here if you’re interested!

The examples you brought up have different code points (otherwise they couldn’t be displayed as different characters without resorting to using pictures). And yes, this can be a bit frustrating, but you’ll get used to it! If you look at your first example, you can see that they are actually made up of the same components, but stacked vertically in one case. There are in fact a whole series of such variants.

I’m not sure what you mean with your follow-up question about traditional characters? In your specific case, one is standard in Hong Kong, the other in Taiwan, but they have probably coexisted for a long time, different government institutions just chose different variants for their respective standards, for some reason!